(Translation) 李重煥 擇里志 總論

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | Records of Selecting Places | |

| Chinese | 擇里志 總論 | |

| Korean(RR) | 택리지 총론(') | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Literati Writings | |

| Type | ||

| Author(s) | 李重煥 | |

| Year | 1751 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | ||

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | Hu Jing | |

| Year | 2018 | |

Introduction

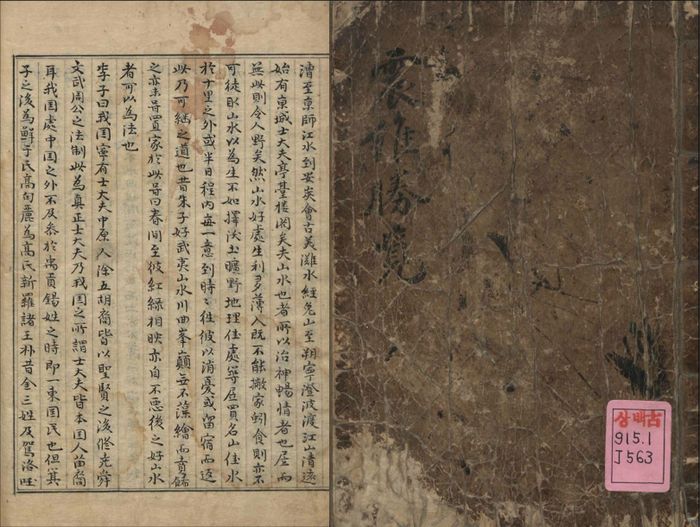

Original Script

| Image | Text | Translation |

|---|---|---|

|

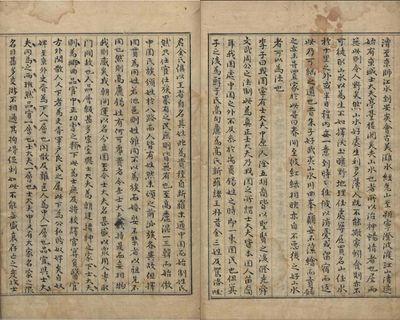

李子曰我國處中國之外旣不參於禹貢錫姓之時卽一東國民也但箕子之後爲鮮于氏高句麗爲高氏新羅諸王朴昔金三姓及駕洛國君金氏俱以王者自命其姓此爲貴種自新羅末通中國而始制姓氏然只仕宦士族略有之民庶則皆無有也 至高麗混一三韓而始倣中國氏族頒姓於八路而人皆有姓然未頒之前派族各異故但擇同貫爲同姓若他邑則姓雖同不以爲族而婚娶不禁者以祖先不同也 然則高麗錫姓有何可尊貴者今世士大夫欲持是而妄相物我則惑矣我 朝開運以名分立國至今士大夫之名甚盛以衆用人專取門閥故也人品層級甚多 宗室與士大夫爲朝廷搢紳之家下士大夫則爲鄕曲品官中正功曹之類下此爲士庶及將校譯官筭員醫官方外閑散人又下者爲吏胥軍戶良民之屬下此爲公私賤奴婢矣 自奴婢而京外吏胥爲下人一層也庶孽及雜色人爲中人一層也品官與士大夫同謂之兩班然品官一層也士大夫一層也士大夫中又有大家名家之限名目甚多交遊不相通其拘碍捉刺如此不能無盛衰存兦之變故士 |

Yi Junghwan(李重煥)[1] says: our country is located outside of China. Our people were not involved in when the emperor of Xia granted surnames to his people, (according to the records) in Tribute of Yu 禹貢[2]. In other words, we have an independent nation in the east of China. However, the descendants of Kija became Sŏnu(鮮于); the descendants of Koguryŏ (高句麗) became the ancestors of Ko(高) family; and the kings of Shilla(新羅) assigned Park(朴), Seog(昔), Kim(金) to his people, and the king of Kaya[3] gave themselves the surname of Kim(金). These are all called aristocratic surnames. Since the end of Shilla, our state has started to communicate with China. From then on, people began to give surnames to themselves. However, only a few officials and prestige families had their own surnames while the commoners did not. Down to the time when Koryŏ united the three kingdoms, (the king) imported Chinese surnames and granted them to people throughout the country so everyone got a surname from that time. Before the king granted surnames, there had been diverse factions and clans. People regard the one from the same ancestral seat as their clansman. If one is from a different ancestral seat but with the same surname, people (usually) do not take him as a clansman of their family. Therefore intermarriage is allowed between people with the same surname since they are considered from different clans. However, why people think the surnames granted by the king of Koryŏ are particularly distinguished? Nowadays, that officials and scholars use that excuse and distinguish themselves from each other makes me so confused. Since Chosŏn was founded with proper justification(名分), the term of scholar-officials(士大夫) are (overly) emphasized. As a consequence, when recruiting officials, the court still exclusively give privileges to power families. The royal family and scholar-officials are the base of the gentry of the dynasty; the group below scholar-officials comprises diverse officials including bureaucratic ranked officials,[4], expectant appointees[5] and personnel managers[6]; the lower is secondary sons of yangban fathers, military officials, interpreters, accountants, doctors and noncommissioned officials, who are the people wandering outside of the (core) bureaucratic system; then who is lower than the above are petty officials, soldiers, and commoners; and people at the bottom are public and private slaves. People from slaves to petty officials outside the capital consist the stratification of the lowborn; secondary sons and officials with miscellaneous posts are comprised of the middle stratification; officials with formal bureaucratic rank and scholar-officials belong to yangban, which could be divided into two minor stratifications again--the scholar-official families can be grouped as power clans and prestige clans, according to different criteria, of which the branches are fairly complicated and (usually) do not communicate with each other. Due to this barrier, the scholar-official families cannot not bear the changes and decline. |

|

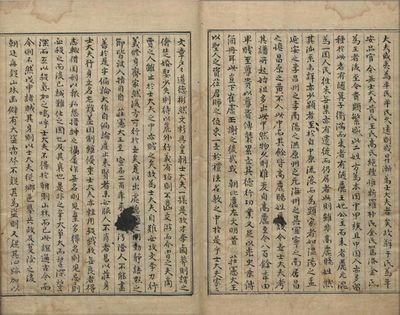

大夫或夷爲平民平民久遠則或昇漸爲士大夫矣故鮮于氏爲平壤品官今無士大夫昔氏高氏絶種惟新羅朴氏金氏及駕洛金氏爲王者後至今貴顯繁盛此二姓方爲本國中甲族且中國人亦多留種於此者有隨箕子衛滿而來者有隨麗王妃公主而來者麗元混爲一國人民往來無禁亦有遷徒而仍居者此則雖非高麗錫姓然其派系未詳亦少顯者至於自中原流落而爲顯家者如溫陽之孟延安之李驪州之李南陽之洪原州之元海州之吳宜寧之南居昌之愼昌原之黃不入於此中而其餘皆高麗錫姓耳故今世士大夫考其譜所起始祖多出此中 然物久則難變自高麗至今八百餘年由卑賤至尊貴以尊貴傳襲累世其德行功業又足以光史乘傳簡策耳此豈下崔盧王謝之後哉我 朝比麗尤文明昔 世宗大王以聖人之資莅君師之位束一世於禮法名敎之中於是乎士大夫家家文章戶戶道德文彩彬然是故才學鹵莽則謂之傖楚婚娶少失則待以荒外行義有玷則不齒交遊而介冑之夫商賈之人雖出於士大夫之中亦賤之矣故爲士大夫自難必攻文學力行義修身齊家然後方可行於世矣是以出處隱顯之間動靜語默之節皆被人指目 自世宗大王至宣廟二百年來時有汚隆人不能盡善於是乎偏論大作自偏輪産出來賢者未必服人不肖者易以藏身士大夫行身立名尤難蓋國制雖優重士大夫亦輕用殺戮故無良者得志輒借國刑以報私怨而搢紳之禍屬作無名則見棄得名則見忌忌則必殺之而後已誠難仕之國也及其衰也是非之爭大爭大而讐深讐深而互以殺戮加之 嗚呼士大夫不得於朝則山林而已此誼通古今而今則不然戊申諸賊其身則以士大夫從鄕邑首事故及芟除之後朝廷每疑山林幽僻有大盜窃發不疑其爲盜則又疑其心跡加以 |

Therefore, occasionally the scholar-officials use to downgrade shift to commoners, and the commoners are also able to gradually upgrade to scholar-officials. Therefore, the Sŏnu(鮮于) families used to be ranked officials in Pyongyang and then collapsed that there is no scholar-official born in that family. Seog(昔) family and Ko(高) family have no descendants and only Shilla Park(朴) family and Kaya Kim(金) family are still continuing their noble status ascending up to the royal lineage. These two clans are exactly the distinct in our state. Moreover, there are also a number of Chinese people remained in our country. For example, there were ones following Jija, ones coming with Wiman(衛滿), and those who accompanied the princesses of Yuan when being married to our country. In particular, during the period when Koryŏ and Yuan were mixed into one state, people traveled across the two countries without any restriction, resulting in that a great number of people immigrated to our country. As to these immigrants, they did not receive the surnames granted by the king of Koryŏ, and their family factions are fairly blurred, and very seldom there are people who get a high position. In terms of Chinese immigrants who became prestige in Korea, there are Onyang Maeng family (溫陽孟氏), Yŏnan Yi family (延安李氏), Yŏju Yi family (驪州李氏), Namyang Hong family (南陽洪氏), Wŏnju Wŏn family (原州元氏),Haeju O family(海州吳氏), Inyŏng Nam family(宜寧南氏), Kechang Shim family (居昌愼氏) and Ch'angwŏn Hwang family (昌原黃氏). The others that are not included in the above surnames are the ones granted by the king of Koryŏ. That is why nowadays when examining the genealogical books of scholar-officials, the majority of their ancestors are those who received the surnames from the king of Koryŏ. However, it is difficult to change when something becomes a convention. Since Koryŏ was founded, it has been 800-odd years. There are (a lot of) families who upgraded from a low status to aristocracy, and their prestige positions have been inherited by generations. Their moral merits and achievements are so great that it is sufficient to glorify and illuminate historical books. How could that be inferior to the descendants of the Chinese prestige families like Cui(崔), Lu(盧), Wang(王), Xie(謝)? Let alone that Chosŏn is a more civilized dynasty than Koryŏ. The sage king of Sejong ascended the throne and became the instructor of Chosŏn people. He adopted rituals, laws, and Confucianism to rule the country. As a consequence, every scholar-official is literary and moral. (They are truly illuminated by) the high attainments. Therefore, if someone is crude and unlearned, then people will call him a savage as if Wu people call Chu people Cangchu(傖楚)[7]; if one makes a small mistake in terms of marriage, he will be treated as a barbarian; and if one has any stained behaviour, he will be isolated by others. Moreover, military men and businessmen are also low people as well even though they were born in scholar-officials' families. Certainly, there are tremendous obstacles for those people if they want to become a scholar-official. They have to commit themselves to study literature, do righteousness, cultivate themselves, regulate the family, and then they are able to behave (as a human being) in the world(行世?). Therefore, all behaviors like going into or withdrawing from the officialdom, active and passive motions will be pointed out by other people. From the reign of the King of Sejong down to the King of Sŏnjo, scholar-officials experience recession and prosperousness during the 200 years. No one could arrive at perfection in everything. As a consequence, partial opinions repeatedly occur, resulting in that even the sages cannot persuade people, unfilial people can easily hide (in the world). And then it becomes much more difficult for scholar-officials to behave themselves and establish the fame (行身立名). Thereupon, the system of the sate put weight on scholar-officials but not employ the severe punishment. So (there is room) for wicked people to get success, and even abuse public power to retaliate against a personal enemy. The literati purges(搢紳之禍) frequently happens. These mean people abandon scholars who have no frame, be vigilant against those who got a frame. Should they feel vigilant, they must slaughter the scholars(無名則見棄得名則見忌忌則必殺之). How difficult it is to be a scholar in our country. Moreover, when their vigilance declines, the debate about right and wrong use to come up. When the debate becomes more and more intense, the vigilance would be more severe. As a result, people will kill each other, (which is internecine). Alas! if scholar-officials cannot achieve their ambition in the court they usually withdraw from officialdom and turn back to mountains and forests, which had been a convention from the ancient times. However, today people cannot go with that convention anymore. In the year of musin(戊申), some bandits, in the name of the scholar-officials, governed mountains and forests(山林). However, the bandits raised a rebellion and then were rooted out by the court. After that, the court is always concerned that bandits might raise a rebellion in remote mountains and forests. If there is no clue for rebellion, the court will doubt if any people have an eccentric mind. |

|

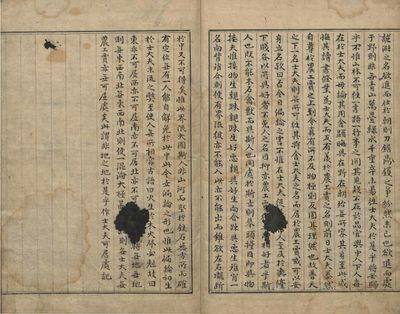

詭僻之名欲進而仕於朝則刀鋸鼎鑊之爭紛然未已也欲退而處于野則非無靑山萬壘綠水千重卒未易往士大夫於是乎將安歸乎 不惟山林不可往一言語一行事之間其見疑不在於品官與中人下人每在於士大夫而毋論其用舍顯晦與在野在朝殆無所容其身至此咸悔其讀書修行爲士大夫而反有羡農工賈之名則前日士大夫泰然自尊於農工賈之上到今眞有所不及物極則反固其理然也故普天之下一名士大夫則無所可往其將舍士大夫之名而居於農工賈或可以安身立名歟 曰否今日偏論之害不惟在士大夫從品官中人至及輿儓下賤各以其所與好者不免人之名目抑亦農工賈獨無所相好者乎 斯人也旣不能木石禽獸而與斯人也同處於斯世則擡頭擧目卽與物接夫惟接物生親踈親踈生好惡親與好生向合踈與惡生離背一名向背離合則便有界限彼亦不能入此亦不能出雖欲左右隴斷於中又不可得矣 惟此界限大囿斯人非山河而堅於鐵石無方向而確有定位無有一人能解脫於此中此今世偏論之形也 惟此偏論初生於士大夫末流之弊至使人無所相容 古語曰火生於木火發必剋故曰東亦不可居西亦不可居南亦不可居北亦不可居如此則將無地無地則無東西南北無東西南北則便一混淪太極圖也如此則無士大夫無農工賈亦無可居處矣此謂非地之地於是乎作士大夫可居處記 |

According to current circumstances, if one wants to go into the officialdom, he will be inevitably involved in (conflict and) severe punishment; if one wants to withdraw from the officialdom and go back to countries, unless he goes to the places hidden among range upon range of mountains and rivers, it is difficult for him to find a proper shelter. Not only are people not easy to go back to mountains and forests, but people's words and deeds are under suspicion, which has nothing to do with ranked officials, chungin or the lowborn. Only scholar-officials are particularly suspected. No matter being employed or abandoned, highly or low ranked, going into or withdraw from the officialdom, scholar-officials cannot find a shelter. As a result, they start to regret that they had studied, cultivated and become a scholar-official. Instead, they feel envious of farmers, artisans, and merchants. In previous days, scholar-officials' station were unperturbedly above over farmers, artisans and merchants. But nowadays, their station seemly lower than others. It is a natural law that things will develop in the opposite direction when they become extreme. That is why once one obtain the name of scholar-official, he would have nowhere to go. Is it able for a scholar-official to settle down (in the world) and establish his fame, if he abandons his title and hides among farmers, artisans, and merchants? The answer is "No". The turmoil of partial opinions (on political affairs) does not only influence scholar-officials. From ranked officials, chungin and the lowborn, everybody can get certain fame from those who get well along with(各以其所與好者不免人之名目). How could it be that no one gets well along with any farmer, artisan, or merchant? A man is different from wood and stone, or bird and beast. As people (with different stations) live in the same world, it is unavoidable to be contacted with each other. Once people start to contact, very naturally, there will be closeness and distantness. Closeness and distantness result in likes and dislikes. Closeness and likes bring about solidarity(向合); distantness and dislikes bring about deviation(離背). Once there are solidarity and deviation, there is a demarcation that people with different stations are not able to cross the boundary, neither to stand in the middle. The demarcation is so clear that it restrains everyone, and it is not like a mountain or river, that (to get rid of it) can be harder than to wear away a stone. The demarcation has no direction but has clear definition that no one can be excluded. That is how the partial opinions are formulated. Initially, the partial opinions were produced by the scholar-officials. However, in the end, the disadvantages make people cannot accommodate each other. There is an old saying that fire generates wood, and once a fire breaks out, the wood must be destroyed. Therefore, if people say neither east, west, south, or north can live, there will be nowhere to live. If it becomes nowhere, there will be no east, west, south or north, and the universe will be mixed up. How could people live without the discrimination of scholar-officials, farmers, artisans, and merchants? Then the earth will become nowhere. That is the reason why I record the earth where scholar-officials live. |

- ↑ the author of the book

- ↑ The Yu Gong 禹貢 or Tribute of Yu is a chapter of the Book of Xia (夏書/夏书) section of the Book of Documents, one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature.

- ↑ Historical sources use a variety of names for Gaya, including Garak (가락; 駕洛, 迦落; [kaɾak]), Gara (가라; 加羅, 伽羅, 迦羅, 柯羅; [kaɾa]), Garyang (가량;加良; [kaɾjaŋ]), and Guya (구야; 狗耶; [kuja])

- ↑ 品官: 품계 있는 벼슬. 품계는 1품에서 9품까지 있으며, 또 정과 종의 구별이 있다.

- ↑ 中正, 중국 위나라 시대에 주ㆍ군에 설치하였던 하급 관직. 이 관직을 통해 인재를 시험한 다음 중앙 관직에 등용하였다.

- ↑ 功曹: 사공司功이라 하기도 한다. 주ㆍ군에 설치하였던 하급 관직으로서 제사ㆍ예악禮樂ㆍ학교ㆍ선거ㆍ고시 따위의 잡다한 사무를 맡았다.

- ↑ 魏晋南北朝时,吴人以上国自居,鄙视楚人粗伧,谓之“伧楚”。因亦用为楚人的代称。