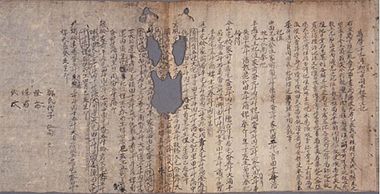

Record of the Property Distribution among Brothers from March 11th, 1601

| Primary Source Document | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | |

| English | Record of the Property Distribution among Brothers from March 11th, 1601 |

| Chinese | 萬曆二十九年二月初七日同生和會文記 |

| Korean | 1601년 하인상 등 화회문기 |

| Document Details | |

| Genre | Social Life and Economic Strategies |

| Type | Record |

| Author(s) | Ha Tŭng? |

| Year | 1601 |

| Key Concepts | |

| Translation Info | |

| Translator(s) | Jamie Jungmin Yoo / Participant of 2016 Jangseogak Hanmun Workshop Program |

| Editor(s) | (Introduction) Martin Gehlmann |

| Year | 2016 |

Introduction

The Japanese Invasions of the Korean Peninsula between 1592 and 1598 not only brought enormous economical costs to Chosŏn Korea, i.e. through the loss of arable land, but also saw an unprecedented displacement of its people. About fifty to sixty thousands prisoners were taken to Japan, where most of them worked as slaves or were further sold to European traders.[1] However, as many prisoners brought with them the culture, skills and trades of their hometowns, their forced exchange led to a substantial transfer of knowledge. Just like Japanese prisoners of war had spurred the development of firearms in Chosŏn and Ming China, Koreans brought new techniques of ceramic production and knowledge of Neo-Confucianism with them to Japan. While in the negotiations between the Chosŏn court and the Japanese after the war the repatriation of all the prisoners was demanded, only the return of 7.500 Koreans is documented. [2]

The absence or loss of family members often presented families in Korea with the dilemma of having to rearrange succession and with it property distribution amongst the remaining family members in a state uncertainty. As Chosŏn was a predominately agrarian economy land was the most valuable property. While formally all land belonged to and was taxed by the King, increasing amounts of land were held in private ownership, mostly by Yangban families employing slaves and servants to work to fields. These families often drafted records of property distribution, in order to legally document the transfer of land to the next generation and to prevent disputes among later generations.

The following two records of property distribution document the serendipitous case of the Ha clan from Chinju, in modern day Kyŏngsangnam-do. Both documents have most likely been drafted by Confucian scholar Ch'angju Ha Tŭng (滄州 河憕) and concern his younger brother named Ha Pyŏn (河忭).

- View together with Record of the Property Distribution among Brothers from 1621.

Primary Source Text

| English | Classical Chinese |

|---|---|

|

This document mentioned on the right is as follows: During the chaos of the Chŏngyu year [1597], our brothers dispersed and went missing. Nothing can be done for the deceased, but one of them has been held captive in the foreign country [Japan]. We still have hope for his return. Five years have passed. Now the Sea of Whale [Hyŏnhaet’an] between us precludes us from receiving reliable news of his whereabouts. He is without an heir, therefore we cannot avoid deciding [his share for the ancestral rites] as early as possible. Shedding tears, we three brothers discussed about how we should allot our property for the ancestral rites first, and then distributed the rest to us. By doing so, without fighting within our own house [meaning, having discord among brothers], we will be able to maintain our slaves without selling off or losing them. If fate be willing and our brother returns safely, Then we would pool all our shares and combine them, and completely re-distribute the whole property to each one, so that no mistake of missing anyone can be made. As for the shrine, we should not arbitrarily give it to other [parts of the] family [a maternal side of family], nor recklessly sell it off. It has to be passed on to our own descendants and should not be replaced [let another family serve it on behalf of us]. If the one in charge of the rites dies without an heir, then we should pass it on to the distant posterity in our family lineage, and should not let it go to the people of another surname [a maternal side of family]. By doing so, the souls without caretakers will be able to return to the proper place to rest. Our elder brother in Ch’irwŏn passed away without an heir. However, his wife has remained chaste since young. How sympathetic with her situation! Although she does not have a right to claim any lands or slaves, we will let her till the field and have slaves so that as long as she lives she performs the ancestral rites properly. Once she passes away, we will select the best lands and the slaves for maintaining the shrine, and then divide her property equally to us. Signed by Insang, representing Mrs Chŏng Signed by Tŭng Signed by Sŏng Signed by Sik |

右文爲: 丁酉之亂, 吾兄弟盡爲蕩沒. 死者已矣 , 或有枝[被]據於異或, 則猶來之望迄 于今五箇歲矣, 今則鯨海■■, 消息難憑, 無後之嗣, 不可不早定, 故唯我數三兄弟泣血, 而議先定祀位, 分執其餘爲去乎 無相閱墻, 鎭長使喚 天旋他日, 幸若生還, 則各歸其衿, 更爲通分處置, 俾無失所之弊爲㫆, 祀位段, 置不得擅許他孫, 又擅自放賣, 傳子傳孫, 不替祀事爲乎矣 若奉祀之人無後爲去乙, 等次傳姓孫, 勿許他姓, 使無主之魂, 永爲依事㫆 七原兄主, 則雖爲無後, 嫂氏靑年守身, 其情可怜, 故田民乙, 不爲分執, 限生前俾令耕使奉祭爲去乎 身後乙良同田民乙, 祀位擇定後, 使孫平均分執事 |

Discussion Questions

- View together with Record of the Property Distribution among Brothers from 1621.

- The family decided to distribute the property while a brother is still in Japan, Why?

- What does this tell us about the importance of property division for families and individuals? Why is this so?

- What do these documents tell us about the way family property was evaluated and divided?

Further Readings

References

- ↑ See Arano Yasunori, The formation of a Japanocentric World Order, The Wako and Change in East Asia, in: International Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 2 No.2, 2005, p. 197 f.

- ↑ See Kim Haboush, JaHuyn; Robinson, Kenneth R. (Ed.) A Korean War Captive in Korea 1597-1600. The Writings of Kang Hang, New York, Columbia University Press 2013, p. IX.