Instructions for the Secret Tally

| Primary Source Document | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | |

| English | Instructions for the Secret Tally |

| Chinese | 密符諭書 |

| Korean | 밀부유서 |

| Document Details | |

| Genre | Royal Documents |

| Type | Instructions |

| Author(s) | King Sŏnjo |

| Year | 1597 |

| Key Concepts | Imjin War, Yi Sunsin, Japan-Korea Relations, King Sŏnjo |

| Translation Info | |

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2016 Jangseogak Hanmun Workshop Program |

| Editor(s) | Hyeok Hweon Kang, Orion Lethbridge |

| Year | 2016 |

Introduction

In 1592, a Japanese invasion of Korea set off the First Great East Asian War.[1] For seven years, this war engulfed the Korean peninsula and its waters with international conflict of rare precedent in world history. Engaging three belligerent states – Ming China, Chosŏn Korea, and a newly unified Japan – the war featured colossal armies, mass-produced firearms and foreign mercenaries. Fighting in this war was Yi Sunsin (李舜臣, 1545-1598), a famed military commander of Chosŏn Korea (1392-1910) who led tide-turning victories against the Japanese navy.

At the outset of the war, the Chosŏn military was woefully unprepared, atrophied by long peace, factional strife and military neglect. On the other hand, forged in a century of war and armed with muskets, Japanese invaders blasted through Korean defenses and took the capital in less than three weeks. Among various factors that enabled the reversal of Japanese forces such as the advent of righteous armies and Ming aid troops, none was more crucial than the role of Yi Sunsin’s navy. His victories at sea helped thwart Japanese advances and unsettled the enemy’s military logistics by blocking their supply routes. Yi often led victories against the odds, enforcing strict military discipline, strategizing with utmost circumspection, and famously deploying turtle ships, an iron-clad with superior firepower and ramming capacity.

Despite his distinguished service, Yi was nevertheless framed and relieved of military command in 1597. At the time, misinformation by a Japanese double agent led King Sŏnjo (宣祖; r. 1567-1608) to order a risky ambush, and Yi was reprimanded and arrested when he hesitated to act on royal order. He was thus imprisoned and demoted to a rank-and-file soldier (白衣從軍). Soon thereafter, on 15 July 1597, the Japanese availed of Yi’s absence and launched a second invasion. At the Battle of Ch’ilch’ŏnnyang (漆川梁), the entire Chosŏn navy was nearly exterminated, save for a small detachment of twelve warships. On 23 July 1597, about a week after the crushing defeat, King Sŏnjo bestowed the following letter of instruction to Yi to remind him of the precarious military situation and reinstate him as regional naval commander (三道水軍統制使),[2] the position of supreme commander for the Chosŏn navy.

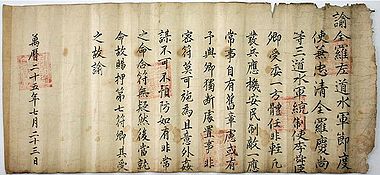

Attached to the letter was also a royal instruction about the secret tally (密符諭書). Customarily, the tally was provided to provincial governors and military commanders who were entrusted with the armed forces of a particular region. The secret tally system was designed to enable the receiving official to dispatch troops swiftly and surreptitiously in case of urgent crises such as rebellions and invasions. As opposed to the more common “troop mobilizing tally” (發兵符), the secret tally was provided only to high-ranking officials and together with a royal instruction. According to procedure, the tally is broken in half, and the king would keep the left half whereas the official would receive the right half. In case of an emergency decree, a royal instruction would be sent down with the king’s tally, with which the official would match his half to confirm its authenticity.

Primary Source Text

| English | Classical Chinese |

|---|---|

| Instruction to Yi Sunsin, the navy commander of left Chŏlla province, concurrently the naval commander of three provinces - Chungch’ŏng, Chŏlla and Kyŏngsang.

My minister, you are entrusted with a region, and the responsibility that you bear is grave. For general matters such as dispatching troops, seizing the opportune moment, calming the people and restraining the enemy, you have established manuals for conduct. [But] I am afraid there may be matters that I, the king, and you must handle independently. Without the secret tally, [this] would be impossible to carry out. Moreover, [we] cannot but take preventive measures against unexpected treachery. If there is an emergency decree, match the tally [with the other half] to clear doubts, and then appropriately undertake the order. Thus, I grant you stamped tally no.7. My minister, you should receive this, and for this reason I instruct you. |

喩全羅左道水軍節度使兼忠清全羅慶尚等三道水軍統制使李舜臣 卿受委一方, 體任非輕, 凢發兵應機, 安民制敵,一應常事, 自有舊章. 慮或有予與卿, 獨断處置事, 非密符, 莫可施為, 且意外姦謀, 不可不預防. 如有非常之命, 合符無疑, 然後當就命故賜押第七符, 卿其受之故諭. |

Discussion Questions

- How does King Sŏnjo present his own role in Yi Sunsin’s demotion and reinstatement? What wrong was done to Yi in the past per this instruction? What can you surmise about the relationship between Sŏnjo and Yi Sunsin? Is the king apologetic?

- Under what circumstances did the king write this instruction to Yi Sunsin? What do the documents above tell us about the military situation in 1597 at the outset of a second Japanese invasion?

- When the king laments the loss of Hansan Island, which battle is he referring to? Why was this battle so important?

- Is the king offering Yi Sunsin a carrot or a stick?

Further Readings

- Swope, Kenneth M. A Dragon’s Head and a Serpent’s Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592-1598. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005.

- Yi Sunsin (1545-1598). Nanjung ilgi: war diary of Admiral Yi Sun-sin. Translated by Ha Tae-hung; edited by Sohn Pow-key. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University Press, 1977.

- Yu Sŏngnyong (1542–1607). The Book of Corrections: Reflections on the National Crisis during the Japanese Invasion of Korea, 1592–1598. Translated by Choi Byonghyon. Berkeley Calif.: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 2002.

References

- ↑ There are various names for this war. In English scholarship, it has been commonly referred to as the Imjin War, Japanese invasions of Korea, Hideyoshi’s invasions or the First Great East Asian War.

- ↑ As shown in the documents below, the literal translation of this title is, “Naval Commander of the Three Provinces of Ch'ungch'ŏng, Chŏlla, and Kyŏngsang.” The regional navy commander served as the supreme commander for the entire Chosŏn navy, and would often be concurrently appointed as navy commander for one of the three provincial navies. The navy commanders of the two other provinces were under the command of the regional navy commander.