Declaration of Prohibitions from Yangjwa Village

| Primary Source Document | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | |

| English | Declaration of Prohibitions from Yangjwa Village |

| Chinese | 良佐洞 洞民의 합의문서[洞案] |

| Korean | |

| Document Details | |

| Genre | Community-Building in Local Society |

| Type | Village Compact |

| Author(s) | |

| Year | 1609 |

| Key Concepts | |

| Translation Info | |

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2016 Jangseogak Hanmun Workshop Program |

| Editor(s) | |

| Year | 2016 |

Introduction

While life in Chosŏn Korea in many ways was defined by a remarkable level of political centralization and the increasing penetration of Neo-Confucian culture into all levels of society, local communities still enjoyed a high degree of autonomy and regional distinctiveness. The two texts selected for this section exemplify ways in which village-level society maintained and carried out local forms of government.

No discussion of Late-Chosŏn local society is complete without a mention of the so-called community compact (Kor. hyangyak). Modelled after the ideas of Zhu Xi (1130–1200),[1] this institution increasingly gained popularity in Korea starting in the latter half of the sixteenth century.[2] Like Zhu Xi before them, Korean literati perceived the compact as an instrument for popular education and edification, which circumvented the need for coercive indoctrination and punitive legalism. In its simplest form, the compact consisted of an agreement entered by all community members, regardless of social status, encouraging them to help each other to act virtuously, to correct each other’s faults, to jointly participate in ritual activity, and to assist each other in times of calamity. Yet, despite the noble intentions that lay at its base, the compact came to function mainly as a tool for provincial yangban seeking to control their communities, while at the same time solidifying local autonomy.[3]

Although we should not underestimate the importance of the community compact in the late Chosŏn period, we also need to qualify the same. The texts show two examples of agreements entered by village residents. Both sought to regulate collective life, but they differed in important ways, telling us something about the complexity and reality of village life as well as the part played by the Neo-Confucian compact therein.

The first text is from Yangjwa Village in Kyŏngju, Kyŏngsang Province, and dates from 1609. It declares a village-wide prohibition on diverting water from the newly constructed dam and irrigation canal and was intermittently reaffirmed throughout the seventeenth century. Its immediate goal was the protection of common economic interests. Attached was a list twenty-two names. These were the members of the village association (Kor. tongyak) and it is apparent that they were all men of high social status, provincial yangban turned community leaders. Significantly, the overwhelming majority belonged to either the Kyŏngju Son or the Yŏju Yi, indicating the preeminent psosition occupied by these two families in the village. Furthermore, the indented names signify concubine descent, which condemned these men to a lower social status, revealing something about status hierarchies in rural Chosŏn. The origins of this form of communal regulation are uncertain, but it likely contained elements that predate the introduction of the Neo-Confucian community compact in Korea.[4]

The second text is from Tunya, 3rd village, in Yangju, Kyŏnggi Province, and probably dates from the eighteenth century. It declares a village compact concerning mutual help in times of bereavement and crisis. The nature of this document differs greatly from the first in its Neo-Confucian rhetoric and focus on ritual propriety even when discussing financial hardship. Of the two, this text most clearly reflects the ideals of Zhu Xi’s community compact.

As these two documents show, village communities in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Chosŏn Korea enjoyed some local autonomy although their politics tended toward domination by local yangban, even as their position was weakening toward the end of the dynasty.[5] They also hint at the variety of communal arrangements that existed in Korean villages, going beyond the community compact and defying straightforward categorization. Oftentimes, several provisions would overlap so that one village could have both an economic-interest association consisting of local yangban and a broader, more porous compact membership geared toward moral cultivation.[6] Yet it is seldom obvious whether a line can or should be drawn between these various forms of community-building arrangements.

- View together with Village Compact from Tunya, 3rd Village.

Primary Source Text

| English | Classical Chinese |

|---|---|

|

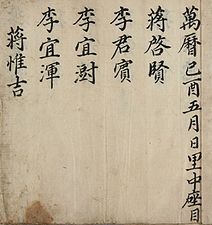

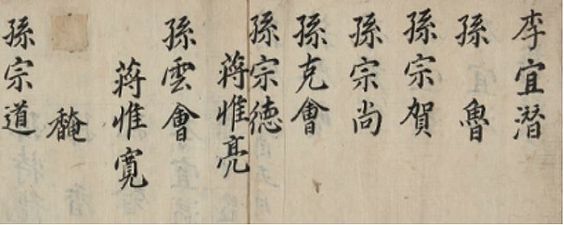

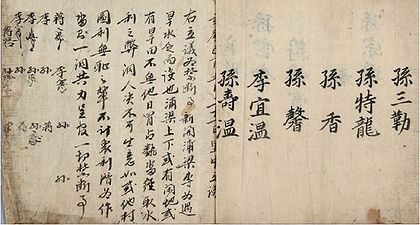

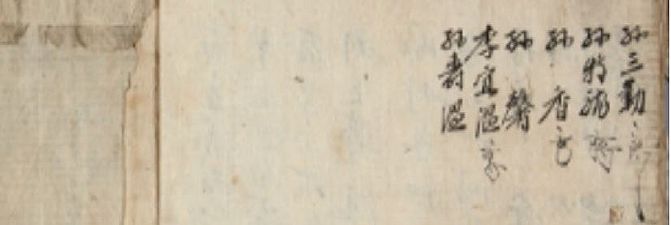

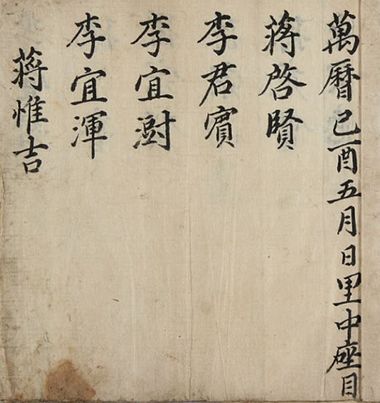

Village association seating order on a certain day of the fifth month, iyu year of the Wanli era [1609] Chang Kyehyŏn Yi Kunbin Yi Ŭiju Yi Ŭihon Chang Yugil Yi Ŭijam Son No Son Chongha Son Chongsang Son Kŭkhoe Son Chongdŏk Chang Yuryang Son Unhoe Chang Yugwan [Son] Am Son Chongdo Son Samgŭn Son T’ŭngnyong Son Hyang Son Hyŏng Yi Ŭion Son Suon Village association declaration on the 21st day of the fifth month, iyu year of the Wanli era [1609] This document is a declaration of prohibitions. The new reservoir was opened solely for the purpose of alleviating water shortages in times of drought. The day may come when the vacant plots and dry fields variously located in the upstream and downstream of the canal will be brazenly occupied and converted to paddy through the deceitful diversion of water. Nevertheless, there is none in this village who has any intention to do so. If a person from some other village shamelessly pursues private gains and surreptitiously develops paddy fields without consideration of public benefit, the entire village will unite to seek administrative redress on these prohibitions. [Signatures] |

萬曆已酉五月日里中座目 蔣啓賢 李君賓 李宜澍 李宜渾 蔣惟吉 李宜潛 孫 魯 孫宗賀 孫宗尙 孫克會 孫宗德 蔣惟亮 孫雲會 蔣惟寬 [孫] 馣 孫宗道 孫三勤 孫特龍 孫 香 孫 馨 李宜溫 孫壽溫 萬曆已酉五月二十一日里中立議 右立議爲禁斷事. 新開浦梁專如遇 旱水乏向設也. 浦渠上下, 或有閑地, 或有旱田, 不無他日冒占飜沓, 經取水利之弊. 洞人決不可生意. 如或他村圖利無恥之輩, 不計象利, 潜爲作沓, 則一洞共力呈官, 一切禁斷事. |

- ''Declaration of Prohibitions from Yangjwa Village''

Discussion Questions

- View together with Village Compact from Tunya, 3rd Village.

- What are the most important differences between the two declarations?

- What does the first document tell us about inter-village disputes and conflict resolution in the response to encroachments?

- The second text underscores the importance of communal involvement in funerary rites. What positive effects were expected to follow from joint ritual practice?

Further Readings

- de Bary, William Theodore. Asian Values and Human Rights: A Confucian Communitarian Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Deuchler, Martina. “The Practice of Confucianism: Ritual and Order in Chosŏn Dynasty Korea.” In Rethinking Confucianism: Past and Present in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Edited by Benjamin A. Elman, John B. Duncan, and Herman Ooms. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Asian Pacific Monograph Series, 2002: 293–334.

- Kwon, Nae-Hyun. “Rural Society and Zhu Xi’s Community Compact.” In Everyday Life in Joseon-Era Korea: Economy and Society. Translated by Edward Park and Michael D. Shin; edited by Michael D. Shin. Leiden: Global Oriental, 2014: 145–154.

References

- ↑ Zhu Xi’s community compact (Ch. xiangyue) was presented in his Lü Family Community Compact, Amended and Emended (Zengsun Lü-shi xiangyue), which, as the title implies, was based on the already existing Lü Family Community Compact (Lü-shi xiangyue), written by Lü Dajun (1031–1082) a century prior.

- ↑ Ch'a Yonggŏl (車勇杰). “Hyangyak ŭi sŏngnip kwa sihaeng kwajŏng (鄕約의 成立과 施行過程).” Han'guk saron (韓國史論) 8, 1980: 189–207.

- ↑ Kwon, Nae-Hyun. “Rural Society and Zhu Xi’s Community Compact.” In Everyday Life in Joseon-Era Korea: Economy and Society. Translated by Edward Park and Michael D. Shin; edited by Michael D. Shin. Leiden: Global Oriental, 2014: 145–154.

- ↑ Kim Yongdŏk (金龍德). “Hyangyak kwa hyanggyu (鄕約과 鄕規).” Han'guk saron (韓國史論) 8, 1980: 208–227.

- ↑ Kim Hyŏk (김혁). “18–19 segi hyangyak ŭi silch'ŏn kwa sahoe kwan'gye ŭi pyŏnhwa: Ch'ungch'ŏng-do Kyŏlsŏng-hyŏn p'ogu maŭl Sŏngho-ri ŭi sarye rŭl t'onghaesŏ (18~19세기 鄕約의 실천과 사회관계의 변화: 충청도 결성현 포구 마을 星湖里의 사례를 통해서).” Han'guk munhwa (한국문화) 66, 2014: 271–306.

- ↑ Kim Hyŏngyŏng (김현영). “Chosŏn chunghugi Kyŏngju Yangjwa-dong ch'ollak chojik kwa kŭ sŏngkyŏk (조선 중후기 경주 양좌동의 촌락 조직과 그 성격).” Yŏngnamhak (嶺南學) 17, 2010: 383–410.