Difference between revisions of "Ontology Design"

(→Node Labels) |

|||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

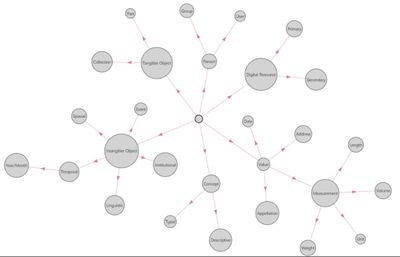

In addition to these six main labels are 22 sub-labels, making 28 labels in total, as shown in the visualization below. These labels, their super-labels, and their definitions outlined in the table which follows. | In addition to these six main labels are 22 sub-labels, making 28 labels in total, as shown in the visualization below. These labels, their super-labels, and their definitions outlined in the table which follows. | ||

| − | + | [[File:MT_FIG_15.JPG|400px]] | |

| + | |||

| + | [http://dh.aks.ac.kr/~lyndsey/MT_ontology.htm Interactive version of the ontology design graph] | ||

{|class="wikitable sortable" style="text-align:center" | {|class="wikitable sortable" style="text-align:center" | ||

Revision as of 15:15, 16 August 2017

Tables featured here are outdated and will be updated soon - 2017-8-1

This section presents existing ontologies or data models relating to cultural heritages, the strategy for the ontology design, and the design itself - including node labels, node properties, relationship labels, relationship properties, and relationships.

Contents

Existing Heritage Ontologies

Other scholars and institutions have previously created ontologies for cultural heritage information, some of which are applicable to a graph database. As mentioned by Doerr (2009), the main ontologies dealing with cultural heritages are the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CIDOC-CRM), Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR), ABC, DOLCE, as well as the Europeana Data Model (EDM) (not mentioned by Doerr as it was released in 2013). These data models were designed with a variety of purposes in mind – some more conceptual and broad, like the CIDOC-CRM, which is closer to an ontology than a practical data model, or the FRBR, which facilitates documentation of a variety artistic and literary works, while others are more functional and specific, like the EDM, which was designed specifically for documentation of items in the Europeana collections.

There have also been explorations of ontologies or data models about Korean cultural heritages, in particular using the models referenced above as a framework, including the work of Kang (2016), Kim (2016), Kim et al (2013), Kim et al (2016), Lee et al (2014), Seo (2014), and kadhlab103 (2017). However, none of these have been geared directly toward an end-goal of facilitating interpretation or the generation of interpretive resources.

Related to cultural heritage graph database models are databases which depict the relationships of historical figures in Asia (such as the China Biographical Database and Wagner-Song Munkwa Project). While these databases are not about cultural heritages, historical figures play a key role as contextual elements of cultural heritage interpretive information, and therefore, these databases could become meaningful resources for data on historical figures and their relationships to one another.

All of these ontologies and data models were designed with the objective of describing cultural heritage-related information. However, their scopes and objectives differ. Many of the ontologies or data models were designed from the perspective of managing institutions, and, as such, are designed for experts who already know what they are looking for (Stiller 2013) and focus on providing metadata information on the heritages themselves, rather than as a way to describe the relationships between heritages and their greater contexts. Some of them have very specific scopes that cannot describe the broad range of cultural heritage information. The CIDOC-CRM does attempt to facilitate a broad description of cultural heritage contexts, but it is too abstract and broad, and not practically applicable to Korean cultural heritage interpretation. Furthermore, none of the existing ontologies are optimized for future use in interpretive resources (in other words, data stored via these ontologies could not be reutilized in various interpretive interfaces, such as an automatically generated, personalized interpretive text). These various limitations of existing ontologies when it comes to the description of Korean cultural heritage interpretive information necessitate the development of a new ontology, designed to convey Korean cultural heritage information in particular, and optimized for future use in various interpretive resource interfaces.

Ontology Scope

This ontology was developed based on a review of the content of the interpretive texts of on-site cultural heritages were translated by the Academy of Korean Studies Korean Cultural Heritage English Interpretive Text Compilation Research Team between fall 2015 and spring 2017 (as discussed in section III.4). The various potential contextual elements, as well as their relationships to the heritage and one another, were extracted from the texts. These were then reviewed and organized, and this has been presented as the following ontology. These texts cover over 130 heritages of 27 different types, thus providing a diverse range of cultural heritage information which reflects the diversity of on-site cultural heritages and their contexts at large.

Design Strategy

This ontology is designed to be applicable to a labeled property graph, such as that facilitated by Neo4J, due to the benefit of being able to more fully incorporate labels and properties of relationships, which is not possible in RDF/OWL ontologies. As mentioned in the previous section, the utilization of a database – a graph database, in particular – in and of itself has the potential to address many limitations of current heritage interpretation practices in regard to the five ideals of heritage interpretation. However, this ontology attempts to take these ideals into particular consideration, while also improving on existing shortcomings in Korean cultural heritage interpretative resources, in the following ways as demonstrated in the following table.

Table

These various features were achieved by taking the following approaches to the ontology design:

- Minimization of node properties in favor of relationships with other nodes: In the existing CHA metadata, for example, the time period of a particular heritage is stored as text. This means that for each heritage, the name of the time period has to be re-inputted by hand. This increases the likelihood of errors and inconsistencies, and increases work - including repetitive translation of the term. However, if a heritage is just connected to the time period via a relationship, the information (including translation) about that time period does not need to be re-inputted again and again. Included in this are measurements, dates, and addresses, for example, which are all their own nodes rather than as properties. This minimizes redundant translation work and facilitates personalization of display and visualization.

- Utilization of node IDs in relationship properties to convey more detailed information about the relationship:*Unlike nodes, relationships cannot have relationships to nodes. Therefore, if additional information about a relationship is needed, this needs to be included as a property. By utilizing the IDs of other nodes in the relationship properties, such the node along with its properties can be accessed and reutilized in an explanation of a relationship, while the number of total relationships in total is minimized. This minimizes graph clutter and redundant information input, and while facilitating richer detail of relationships.

- Minimization of event nodes in favor of relationships with properties: In CIDOC-CRM event nodes are used for even relatively simple actions. However, this makes the path between nodes unnecessarily long. This ontology uses relationship properties to convey additional information about relatively simple actions (such as re-tiling, renovation, etc.), and only includes complicated events with many actors and sub-events in the event label (such as a war or political event). This minimizes redundant translation work and shortens the path between related nodes.

- No separate label for cultural heritages:Although this database is designed around Korean cultural heritages, cultural heritages are not given their own label. This is because they are not fundamentally different from other tangible objects. However, their status as a CHA-designated cultural heritage is trackable via designation relationships which connect a tangible object to its heritage designation, if it has one.

- Facilitation of multi-language (measurement, calendar system) display via node properties:Included in node properties are various languages (Korean, English, and Chinese characters), measurement systems (metric or imperial), and calendar systems (solar, lunar, and reign years) to allow for searching and display of information in diverse ways suited to the needs of the user. With measurements and dates/years stored as nodes themselves, this minimizes redundant translation work of simple things like dates and measurements. This also allows for one user to search for and present information in a particular language (or measurement/dating system), and display it in another, even if they do not know that language themselves. Simple definitions of difficult terminology are also included as properties to allow users with less background knowledge to understand the terminology.

- Inclusion of objective and subjective value judgments (such as oldest, first), quality judgments (such as refined, grandiose):The reason cultural heritage become cultural heritages is that experts deem they have some particular value which warrants preservation. However, often these claims are not clearly conveyed in current interpretive texts, or they are subjective (such as saying a painting is “refined” without any specific reason for such a claim or any clear definition of what “refined” means). By including value judgment in the ontology, heritages which have similar value will be able to be searched for. In addition, we will be able to see how often heritages are described with vague or baseless subjective descriptions, so that we can research more specific and meaningful ways to express the subjective value of heritages and minimize unhelpful filler words all so common in current interpretive texts.

- Tangible object parts described as nodes: It is useful to have parts of heritages – such as the rooms of a building or the various body parts of a Buddhist statue – as their own nodes so they, too, can have type and quality relationships which can be compared to other similar heritage parts and so that users can search/browse for heritages via the characteristics of its parts.

- “Meta” labels for transparency of data and data management:Meta labels for relationships, as well as a user label for nodes, allows for information on the creation, translation, editing, and source citation for information within node properties and relationships to be included in the database, but also easily excluded from search results if necessary. This allows for searching for relationships which do not have any cited evidence and may be less reliable. There is also a relationship property, “veracity,” which can identify “presumed” relationships which do not have any specific source (such as guesses about the time period of a heritage). This addresses current problems of lack of responsibility and oversight for information and translation in interpretive texts and gives users the power to judge the evidence behind claims.

- Inclusion of resources for further engagement via an “engage” relationship label: In order to facilitate user's discovery of further reading and educational opportunities related to heritages, an “engage” relationship label was included so that users can easily access to further information about the heritages, concepts, historical figures, places, etc., in which they are interested.

These features will be explained in greater detail in the following section on the ontology design itself and via the ontology examples in section VII.

Design

This section outlines the ontology design itself, including node labels and properties, relationship labels and properties, as well as the relationship types themselves. In other graph database frameworks such as RDF/OWL, nodes are referred to as entities or individuals, labels are referred to as classes, node properties are referred to as attributes or datatype properties, and relations are referred to as object properties. However, since the ontology presented here is implemented via a labeled property graph as presented in Robinson et al (2005), the terminology of labeled property graphs will be used instead of RDF/OWL terminology.

Node Labels

The node label design took inspiration from the classes of the CIDOC-CRM. However, the CIDOC-CRM is more complex than is needed to convey interpretive information, and furthermore, its event-based perspective is unconducive to providing content in multiple languages. More simple ontologies which use just actor, event, place, object, and concept are intuitive and can be used broadly for many purposes, but lack systematic rational and nuance, failing to take into consideration the differing node properties and relationships for the kinds of entities which would fall into those labels (for instance, person, institution, and group, are all “actors,” but would each have very different attributes and relations). Therefore, the ontology presented here strives to find a middle point on this spectrum, such that the ontology is not too specific that a wide variety of users can use it to various objectives, but also not so general that nodes with different property and relational needs are grouped together.

The ontology proposed here has six main labels: tangible object, intangible object, person, concept, digital resource and value. These labels were determined based on the ideas of tangibility and whether or not it can have more than one existence. For example, tangible object and person are tangible, digital resource is digital, and intangible object, concept, and value are intangible. Tangible object, person, intangible object, and value can only have once instance, while concept and digital resource can have multiple instances. Value and concept were differentiated because the definition of value is permanent, while concepts can change meaning over time. Person was differentiated from tangible object, partially on the basis of being alive (although in this case, plants and animals would also need to be differentiated from tangible objects), but mostly out of usefulness for the user.

| Class | Existances | Start/End | Manifestation | Agency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible Object | Singular | Yes | Physical | No |

| Intangible Object | Singular | No | Not Physical | No |

| Person | Singular | Yes | Physical | Yes |

| Concept | Multiple | No | Not Physical | No |

| Value | Singular | No | Not Physical | No |

| Digital Resource | Multiple | No | Digital | No |

In addition to these six main labels are 22 sub-labels, making 28 labels in total, as shown in the visualization below. These labels, their super-labels, and their definitions outlined in the table which follows.

Interactive version of the ontology design graph

| Class Name | Level | Superclass | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| DM Entity | 0 | - | not a used class; just a way to link first level classes together |

| Tangible Object | 1 | DM Entity | an entity that has a singular, tangible manifestation, and that is not a human |

| Intangible Object | 1 | DM Entity | an entity that has a singular manifestation, but which is not physical |

| Person | 1 | DM Entity | an individual human being |

| Concept | 1 | DM Entity | an entity with a definition that can be applied to many instances of other nodes |

| Value | 1 | DM Entity | an entity that is singular, can be used to describe multiple entities, and has a single interpretation |

| Digital Resource | 1 | DM Entity | an entity that exists in digital form and are referents to other entities |

| Collection | 2 | Tangible Object | an entity which is a group of multiple tangible entities |

| Part | 2 | Tangible Object | an entities which is a section of a tangible object which, while can be described in isolation, cannot exist apart from the tangible object |

| Temporal Object | 2 | Intangible Object | an entity which is a span of time with a start and end |

| Spacial Object | 2 | Intangible Object | an entity with geographic coordinates, either a specific location or a range of land/sea/space |

| Institution | 2 | Intangible Object | an entity which is popularly or legally recognized and has agency, but which need not necessarily have physical manifestation |

| Event | 2 | Intangible Object | an entity comprised of various actions by various actors that occurs over a period of time |

| Linguistic Object | 2 | Intangible Object | an entity composed of linguistic content; not the physical or auditory manifestation of the content, but the content itself |

| Group | 2 | Person | a group of people |

| Typal Concept | 2 | Concept | an entity which can describe the form or type of other entities |

| Descriptive Concept | 2 | Concept | an entity which describes the quality or nature of another entity (i.e. adjectives) |

| Appellation | 2 | Value | an entity that is a simple string, usually used in a situation of name change over time |

| Date | 2 | Value | a day, month, or yea |

| Measurement | 2 | Value | an entity used to express dimensions |

| Address | 2 | Value | a specific geo-spacial location that can be described by a single GIS coordinate pair or a street address |

| Primary Resource | 2 | Digital Resource | a digital media entity in their direct form (i.e. the file itself, .jpg, .mp3, etc.) |

| Secondary Resource | 2 | Digital Resource | a compilation of digital media |

As mentioned in the previous section, an effort was made to facilitate the node-ification of items typically stored as properties, such as appellations, dates, addresses, and dimensions. This allows for equivalent information to be conveyed via multiple languages, calendar systems, measurement systems, etc. Furthermore, address and spatial objects, as well as date and temporal object, were differentiated rather than grouped as “place” or “period.” This is because addresses and dates are permanent, while spatial and temporal objects can change over time. Furthermore, events and temporal objects were distinguished from one another in that events must involve various actors engaging in a variety of connected actions, while a temporal object can be just a general period of time.

Node Properties

As explained in the section on design strategy, node properties were minimized in favor of more discrete nodes which are connected to via relationships whenever possible to minimize redundant translations and other data input. Therefore, the node properties were limited to the following as shown in the table below.

| Property Name | Domain | Data Type | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIS | address | gis | latitude and longitude coordinates |

| ID | ALL | string | id |

| title_kr | ALL | string | main name in Korean |

| title_en | ALL | string | main name in English (translation) |

| title_ch | ALL | string | main name in Chinese (hanmun) |

| title_rr | ALL | string | main name in Revised Romanization |

| title_mr | ALL | string | main name in McCune-Reischauer |

| title_kr_alt | ALL | string | alternative name in Korean |

| title_en_alt | ALL | string | alternative name in English |

| def_kr | ALL (except value) | string | definition, summary, explanation in Korean |

| def_en | ALL (except value) | string | definition, summary, explanation in English |

| URI | ALL (except value) | string | link to a webpage describing the node |

| date_sol | date | date | date in the solar calendar |

| date_lun | date | date or string (?) | date in the lunar calendar |

| date_kr | date | string | date based on Korean reign years |

| date_ch | date | string | date based on Chinese date naming |

| CHnumber | tangible objects | number | cultural heritage designation number |

Some limitations of these node properties are that there can be only one main title for each language. For example, the primary name that will show when the node is displayed in Korean or English will need to be decided. For example, “pagoda body” is referred to by many names in Korean, while events such as “Imjinwaeran” are translated variously in English as the 'Japanese Invasions of Korea,' the 'Imjin War,' etc. Which term appears as the primary title of the node in each language should be determined based on research of 1) how it has been most commonly referred to or translated as, and 2) what is easiest for most audiences to understand. However, all equivalent terms or translations can be saved as appellation nodes, which allows for users to search for and find the nodes via these alternate names.

Relationship Labels

Relationships were also given labels. These were based on the kind of relationships found within on-site interpretive texts, as well as the property needs of each relationship type. There are 15 labels as follows. Including these relationship labels will be helpful later when users want to find specific kinds of relationships among the many relationships; For instance users can sort for information about the value of the heritage, the history of the heritage, the history of related historical figures and events, related concepts, the various elements of the heritage and their artistic qualities, related multimedia or reference materials, etc., depending on their areas of interest.

Table

Relationship Properties

In addition to labels, relationships were given properties. Which properties a relationship has depends on the label it has, just like nodes. All relationships have some basic properties. These allow the relationships to be displayed in various languages and to identify the creator, creation date, and reference material of the relationship. However, relationships with action, start, end, transformation, value labels also have additional properties as follow. These utilize the IDs of other nodes which can be drawn upon to describe information about additional factors of the relationship – including when, where, why, and by whom it happened. Examples of how this feature can be used is explained in the next section.

Table

Relationships

The following is a list of the relationships and their inverses for the ontology. The relationship label determines the possible domains and ranges for the relationships, which can be found in the previous section on relationship labels.

Table

However, it was found that the potential relationships and inverses for action, start, end, and transformation relationships were more complicated than basic standard-inverse relationships. This is because the domain and range of the relationship can depend on the nature of the relationship. Therefore, there are four columns - active, passive, date, and place. Passive, date, and place can all be inverses of active. However, date and place can also be the inverse of passive as well. This depends on whether the relationship is centered around a human action, or a passive effect on a person or heritage object in which the actor of that effect is insignificant. For example, if a building is renovated, it is usually the date of renovation which is important, and who renovated it is secondary. In this case, the relationship would be between the heritage and the date via the “wasRenovated” relationship, and who renovated it would be stored as a property. However, there are also cases in which who did the action is more important than when it was done - for example, who created a piece of art. In this case, the relationship would be between the creator and creation, with the date saved as a property. This allows for flexibility in deciding which should be the target (range) of a particular relationship, but also may prove to be problematic as the range type is then selected based on the subjective judgment of the relationship creator. However, regardless, all the important information about the relationship - actor, place, date, reason, etc., can be stored as a property.

Table