(Translation) 乾隆十五年庚午四月十五日 李奴 丁山 明文

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | Bill of Sale to Jeongsan, a slave of Yi [Naebeon], on the 15th day of the 4th month in 1750 | |

| Chinese | 乾隆十五年庚午四月十五日 李奴 丁山 明文 | |

| Korean(RR) | 건륭십오년 경오 사월십오일 이노 정산 명문(Geollyungsibonyeon gyeongo sawol siboil Ino Jeongsan Myeongmun) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Historical Manuscripts | |

| Type | Record | |

| Author(s) | Slave Yi Subong in Gangneung 江陵 奴 李守鳳 | |

| Year | 1750 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | bill of sale, slave, women's inherited property | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | Sanghoon Na | |

| Year | 2018 | |

목차

Introduction

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

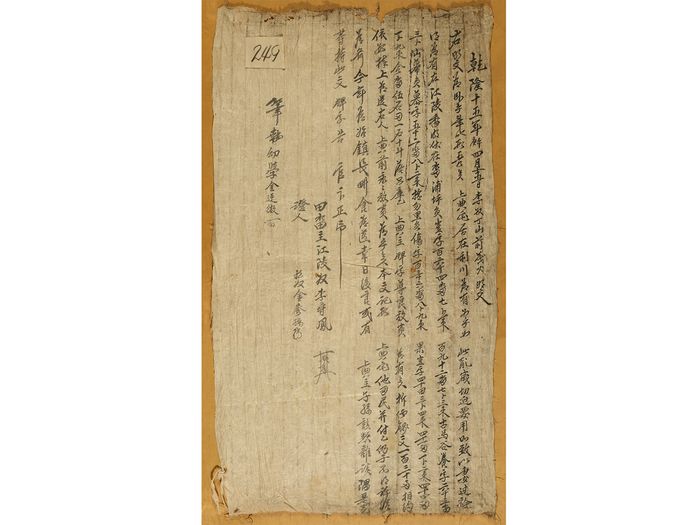

乾隆十五年庚午四月十五日李奴丁山前茂火明文 右明文爲臥乎事叱段吾矣 上典宅居在利川爲有爲乎爲 此亂歲切迫要用所致以妻邊衿 得爲有在江陵香湖伏在畓浦坪員豈字百六十四畓七卜一束 百九十二畓七卜三束古馬谷養字六十三畓 三卜 山幕員慕字五十二畓八卜二束 檢勿里員傷字百三十二畓八卜九束 果豈字四十田三卜四束四十一田一卜二束四十四田 一卜九束僉畓伍石田一石十斗落只庫乙 上典主 牌子導良放賣 爲有矣折價錢文一百三十兩相約 依數捧上爲遣右人 上典前永永放賣爲乎矣本文記段 上典宅他田民幷付乙仍于不得許給 爲有今年爲始鎭長耕食爲遣幸日後良或有 上典主子孫族類雜談隅是去乙 等持此文牌子告 官卞正印 田畓主江陵奴李守鳳[手寸] 證人 私奴金參孫[署押] 筆執 幼學 金廷徽[署押] |

(translation) III-2. 乾隆十五年庚午四月十五日 李奴丁山前茂火明文 The bill of sale[1] for Jeongsan, slave of Yi [Naebeon],[2] on the 15th day of the 4th month of the 15th year [1750] of Emperor Qianlong’s reign [1735-1796]

The purpose of the present bill of sale is as follows:[3]

My master [Mr. Song] lives in Icheon[4] and the famine is so severe this year.[5] Thus, out of sheer necessity, I[6] received a letter of authorization[7] and sold his wife’s inherited property located at Lake Hyang in Gangneung: the 164th rice paddy of the gi[8] land on Popyeong Plain, producing seven loads[9] and a bundle[10] of grain; the 192nd rice paddy [of the gi land], producing seven loads and three bundles of grain; the 63rd rice paddy of the yang[11] land at Goma Valley, producing three loads of grain; [the 52nd rice paddy of the mo[12] land on Sanmak Plain][13]; the 132nd rice paddy of the sang[14] land on Geommulli Plain, producing eight loads and nine bundles of grain; the 40th farm field of the gi[15] land, producing three loads and four bundles of grain; the 41st farm field [of the gi land], producing one load and two bundles of grain; the 44th farm field [of the gi land], producing one load and nine bundles of grain. In total, they are five seok[16] of rice paddy and one seok and ten durakji[17] of farm field.

130 nyang of coin is agreed between us as a set price. I accept the amount and sell the property in perpetuity to [Jeongsan’s] master mentioned on the previous line. [However,] the original document[19] cannot be given because the record of my master’s other lands and slaves is also included in it. From this year on, you may cultivate crops for good. By any chance, should there be room for a dispute at a later date among my master’s children, take this document with the letter of authorization and report to the authorities for justice in this matter.

The owner of the rice paddies and farm fields: Slave Yi Subong in Gangneung [Signature of Finger Joint]

Witness: Private Male Slave Kim Chamson [Signature]

Scribe: Scholar[20] Kim Jeong-hwi [Signature]

|

Discussion Questions

Further Readings

References

- ↑ A bill of sale (myeongmun 明文) was given to a buyer when a deal was concluded between two individuals privately before having a government’s warrant.

- ↑ Slave Jeongsan is carrying out this business for his master Yi Naebeon (1703-1781). The yangban literati considered it inappropriate to be involved in business transactions themselves during the Joseon period.

- ↑ The literal translation of this sentence would be “The bill of sale mentioned on the right is as follows.” There are two explanations on the usage of wu 右 (“right”): one is that it refers to the word “bill of sale” 明文 written vertically on the right side. The other is that it suggests the document placed in a ruler’s right side which he was supposed to deal with first. Thus, wu 右 means the present document, which is based on A Clear Distinction of Styles (Wenti mingbian 文體明辨). See Kim Seong-gap, “Joseonsidae myeongmun e gwanhan munseohakjeok yeon-gu 朝鮮時代 明文에 관한 文書學的 硏究,” (Ph.D. Diss., The Graduate School of Korean Studies, 2009), 66-7.

- ↑ This is presumed to be Icheon in Gyeonggi province.

- ↑ This was a typical statement of contracts because it was forbidden for people to sell their inherited lands at their disposal in the Rank Land Law (gwajeonbeop 科田法). However, in the sixth year of King Sejong’s reign, it was allowed in such urgent situations as providing for the funeral and burial of their parents, repaying their outstanding debts, or escaping from the grinding poverty. See Veritable Records of King Sejong, Year 6 (1424), Month 3, Day 23, Entry 3. (available at http://esillok.history.go.kr/front/index.do). Thereafter, people usually started with plausible excuses when they wrote this kind of document.

- ↑ This refers to Mr. Song’s male slave Yi Subong. He is carrying out this business on behalf of his master.

- ↑ A letter of authorization (baeja 牌子) was used to represent or act on another’s behalf in private affairs, business, or some other legal matter.

- ↑ Gi 豈 is the 157th character in the Qianzi wen 千字文 (Thousand Character Classics), which is used to refer to the location of the land.

- ↑ The character for “load” is bu 負 (“burden”) or bu 卜 (“Korean A-frame carrier”), which is the amount of crop yields that a man could carry on his back with the A-frame carrier. Korean land measurement for taxation also used a measure of productive capability (gyeolbu 結負) expressed in surface area. See James B. Lewis, Frontier Contact Between Chosŏn Korea and Tokugawa Japan (London: RoutledegeCurzon, 2003), 30.

- ↑ The character for “bundle” is sok 束 (“bind”), which is the amount of rice plants. A handful of rice plants are called one pa 把 (“to grasp”). Ten handfuls (pa) of rice plants make one bundle (sok).

- ↑ Yang 養 is the 156th character in the Qianzi wen.

- ↑ Mo 慕 is the 162nd character.

- ↑ There is a circle drawn around this rice paddy in the original document, which meant to be deleted. It was not supposed to be sold.

- ↑ Sang 傷 is the 160th character.

- ↑ Gi 豈 is the 157th character.

- ↑ Seok 石 (seom in vernacular Korean) refers to seomjigi 石落只, which is the amount of land on which one seom (180 liters) could be planted as seed. The size of land has varied at different regions. It is approximately 1500-3000 pyeong (4,950-9,900 square meters) for rice paddies and 1000 pyeong (3,300 square meters) for dry fields.

- ↑ Durakji 斗落只 or durak 斗落 (majigi in vernacular Korean) is the amount of land on which one mal (18 liters) could be planted as seed. The size of land has varied in different regions. It is approximately 150-300 pyeong (495-990 square meters) for rice paddies and 100 pyeong (330 square meters) for dry fields. See James Palais, Confucian Statecraft and Korean Institutions (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1996), 364.

- ↑ The character 中 is missed here. 良中, pronounced as ahi in idu reading, is a locative postposition, meaning “at.” The idu script is a writing system which uses Chinese graphs for the pronunciation and transcription of native Korean affixes, words, and sentences. This writing was used to clarify the meaning of legal documents written in literary Chinese. For further information, see Richard Rutt, “The Chinese Learning and Pleasures of a County Scholar,” Transactions of the Korea Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 36, (April 1960): 16-21.

- ↑ This refers to the document of property distribution given to Mr. Song’s wife.

- ↑ The characters for a “scholar” are yuhak 幼學, which literally means a “young learner” who did not pass the civil service examination yet. JaHyun K. Haboush translates it into a “student scholar” (Haboush, The Confucian Kingship in Korea, 90) and Eugene Y. Park renders it into a “degreeless scholar.” (Park, Between Dreams and Reality, 41).

Translation

- Discussion Questions: