"(Translation) 彙纂麗史 凡例"의 두 판 사이의 차이

(→Original Script) |

|||

| (같은 사용자의 중간 판 3개는 보이지 않습니다) | |||

| 1번째 줄: | 1번째 줄: | ||

{{Primary Source Document3.1 | {{Primary Source Document3.1 | ||

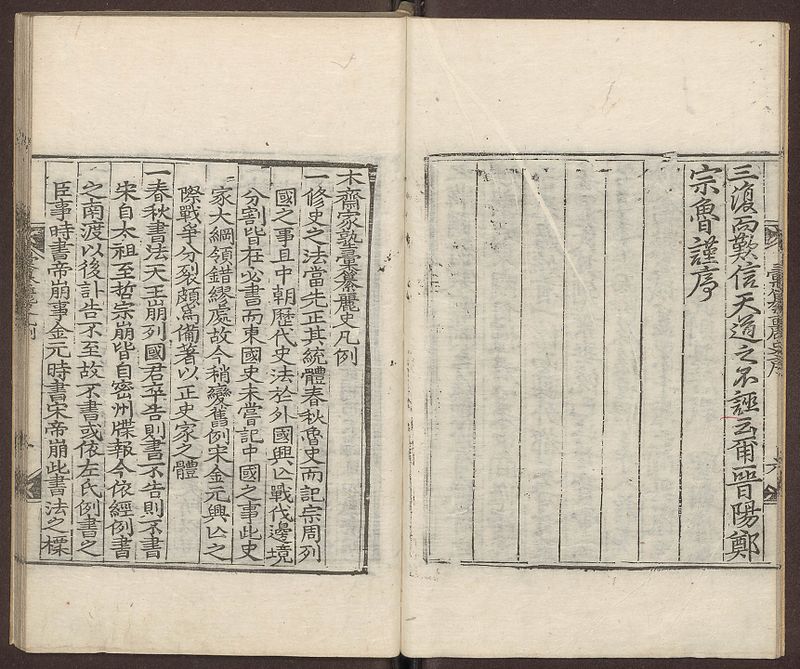

|Image = 목재가숙휘찬려사범례1.jpg | |Image = 목재가숙휘찬려사범례1.jpg | ||

| − | |English = Explanatory Notes on the Compiled Edition of Koryŏ History | + | |English = Explanatory Notes on the Style and Format of the ''Compiled Edition of Koryŏ History'' |

|Chinese = 彙纂麗史 凡例 | |Chinese = 彙纂麗史 凡例 | ||

|Korean = [http://jsg.aks.ac.kr/data/viewer/bookImage.do?callNum=K2-53&vol=001&pgID=008 목재가숙 휘찬려사(''Hwichʻan yŏsa'') 범례] | |Korean = [http://jsg.aks.ac.kr/data/viewer/bookImage.do?callNum=K2-53&vol=001&pgID=008 목재가숙 휘찬려사(''Hwichʻan yŏsa'') 범례] | ||

| 8번째 줄: | 8번째 줄: | ||

|Author = 洪汝河 | |Author = 洪汝河 | ||

|Year = mid-17th century | |Year = mid-17th century | ||

| − | |Key Concepts= Historiography, Koryŏ History, International Relations, Confucianism | + | |Key Concepts= Historiography, Koryŏ History, International Relations, Sino-Korean Relations, Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism |

|Translator = [[2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced)#Participants | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group)]] | |Translator = [[2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced)#Participants | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group)]] | ||

|Editor = King Kwong Wong | |Editor = King Kwong Wong | ||

| 17번째 줄: | 17번째 줄: | ||

=='''Introduction'''== | =='''Introduction'''== | ||

| + | |||

| + | (TBA) | ||

=='''Original Script'''== | =='''Original Script'''== | ||

| 33번째 줄: | 35번째 줄: | ||

|| | || | ||

| − | Explanatory Notes of the Compiled Edition of Koryŏ History | + | Explanatory Notes on the Style and Format of the ''Compiled Edition of Koryŏ History'' |

| − | + | One. As to the method of compiling history, one should first set aright its unifying style. The ''Spring and Autumn'' [''Annals''] is a history of the state of Lu, but it also records the affairs of the Zhou and its feudal states. In addition, as to the historiographical principles throughout the past dynasties of the central court, regarding the rise and fall of foreign states, warfare, and division of borders, whenever they exist, all are written. On the other hand, the histories of the Eastern Country never once record the affairs of China – this is an error in the general guiding principles of historians. As a result, now I deviate from the precedents. In between the rise and fall of the Song, Jin, and Yuan, warfare and division are rather detailly written, thereby rectifying the standard of historians. | |

| − | + | One. According to the historiographical principles of the ''Spring and Autumn'' [''Annals''], [the death of] the heavenly sovereign is written as “demised”, and the [death of] various state rulers is written as “deceased”. Whenever [the obituary] was received, then it is written; whenever it was not, then it is not written. During the Song from Taizu (r. 960-976) to Zhezong (r. 1085-1100), the obituary of the emperor all came from the government reports dispatched from Mizhou<ref>nowadays in Shandong province, China</ref>, now following the precedents of the classics I write them. After [the Song] crossed the river south, the obituary did not reach [the Eastern Country], therefore it is not written, or following the example of Mister Zuo<ref>This refers to Zuo Qiuming 左丘明 (556-451 BCE), the author of the ''Zuo Commentary'' 左傳.</ref>, it is written. When [the Eastern Country] submitted and served [the Song], [the death of] the emperor is written as “the emperor demised.” When [the Eastern Country] served the Jin and Yuan, [the death of the Song emperor] is written as “the Song emperor demised.” This is the standard of historiographical principles. | |

|- | |- | ||

| 60번째 줄: | 62번째 줄: | ||

|| | || | ||

| − | + | One. As to the style and format of the ''History of Koryŏ'', they follow [the standard of] the ''History of Yuan'' for the writing of various treatises. One by one each entry is listed and recorded, like government institutions and ritual protocols; this is not the standard of writing history. Now I imprudently follow the historiographical principles of previous dynasties, alter the composition of various treatises, synthesize the entries into proses. The evolution of the institutions of astronomy, geography, military affairs and punishments during the 500 years are all assembled into proses, so that their summary and entire discourse, as well as advantages and disadvantages, can be observed clear-sightedly. Therefore, the form of biographies and treatises should be established together with the that of chronicle; each makes use of the other. One should not emphasize one form at the expense of another. | |

| − | + | One. As to the various prominent ministers, take those who had the same affairs or similar achievements, reputations, and backgrounds, put them as group according to their kind to write their biographies, and attach to them my commentaries. All follow the historiographical principles of [the ''Book of''] ''Han'', [the ''Book of''] ''Jin'', [the ''Book of''] ''Tang'', and [the ''History of''] ''Song''.<ref>The ''Book of Han'' 漢書 was written by Ban Gu 班固 (32-92 CE) and completed by Ban Zhao 班昭 (45?-116? CE) during the Eastern Han period (25-220 CE). The ''Book of Jin'' 晉書 was compiled by Fang Xuanling 房玄齡 (579-648 CE) in 648. There are two books of Tang – the ''Old Book of Tang'' 舊唐書 and the ''New Book of Tang'' 新唐書. The ''Old Book of Tang'' was compiled by Liu Xu 劉昫 (888–947 CE) in 945 and the ''New Book of Tang'' was compiled by Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007-1072 CE) in 1060. The ''History of Song'' was compiled by Toqto'a 脫脫 (1314-1356 CE) in 1345.</ref> | |

| − | + | One. The gain and loss of borderland are important affairs that bind the whole state. For example, the return of P'oju (RR: Poju) <sub>now Ŭiju (RR: Uiju)</sub> to Koryŏ (RR: Goryeo) is recorded in the ''Mirror of the Song''<ref>Its alternative title is 增修附註通鑑節要續編. It was compiled by Liu Shan 劉剡 and edited by Zhang Guangqi 張光啓 during Ming Xuanzong’s 宣宗 reign (1426-1435 CE).</ref>. Even the ''Comprehensive Mirror of the Eastern Country''<ref>It was compiled by Sŏ Kŏchŏng 徐居正 (RR: Seo Geojeong, 1420-1492 CE) and completed in 1485.</ref> and the other books, all leave out and do not record it. In addition, cases, such as the two physicians travelled back and forth [between Koryŏ and Song] during the reign of Huizong (r. 1100-1126) are particularly illuminating that cannot be left out and not written. Now following the ''History of Song'' all are written. | |

| − | + | One. As to the wars waged on the Eastern Country, all are verified with the historical records of the central court, tracing the roots of such calamity, and written. | |

| − | + | One. As to Ch’ungsuk (RR: Chungsuk) and Ch’unghye (RR: Chunghye) proclaimed new reign after each other,<ref>This refers to the fact that they consecutively succeeded each other, thus both had a second ascension after the other’s dethronement.</ref> the old format of the ''History of Koryŏ'' is particularly wrong. Now all are rectified. | |

| − | + | One. As to the historians’ methods of writing of sentences, the usage of words has its own methods and precedents. People of the East do not know this, and their way of narration often uses unpolished expressions to complete the sentences. Now I imprudently revise and alter them, replacing them with other words. As for the cases that involved places of uncertainty, I dare not imprudently write down a single word to make up. Those of which I added in from other books, all are cited with their origins. | |

| − | + | One. As to the histories of previous dynasties, all have appendix on foreign barbarians. Now I imprudently follow them and write Kitan, Japan and other biographies. | |

|- | |- | ||

| 80번째 줄: | 82번째 줄: | ||

|| | || | ||

| − | ( | + | One. The compilations of histories of the central courts – the two Han, the Jin, the North and South dynasties, the Tang, and the Song, all regard highly on the annals and biographies [style]. For example, the ''Annotated Outline of the Comprehensive Mirror''<ref>It was compiled by Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130-1200 CE) and is the first ''kangmok'' style history of its kind.</ref> was not composed by court historians, but using the annals and biographies of previous histories as basis, the authors rewrite them for their own convenience, thus its prose is splendid and worth reading. Although the Eastern Country has its own biographies, its proses are vulgar and not elegant. The ''Comprehensive Mirror of the Eastern Country'' and other documents one after another follow them. Therefore, they do not reach the refinement of the histories from China. Here I take various biographies and slightly affix my deletion and embellishment: matters are added from the old by one tenth, and words are deleted from the former by six tenths, so as to wait for those who actually write histories to collect and compile it into a chronicle and tighten it up into a great classic of the Eastern Country. |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

*Discussion Questions: | *Discussion Questions: | ||

| − | + | # How does Hong Yŏha think about the style and format of the ''Koryŏsa''? What are the reasons for him to justify such changes? | |

| + | # How does this text reflect the worldview of Chosŏn intellectuals? Considering this text was written in the mid-17th century, how does this text reflect Chosŏn's geopolitical situation of that time? | ||

| + | # What kind of Confucian value is embodied in this text? | ||

| + | # How does this text tell about the author's perception of the Han and non-Han dynasties of China? Why does the author have such perception? | ||

=='''Further Readings'''== | =='''Further Readings'''== | ||

2018년 7월 26일 (목) 10:46 기준 최신판

| Primary Document | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | Explanatory Notes on the Style and Format of the Compiled Edition of Koryŏ History | |

| Chinese | 彙纂麗史 凡例 | |

| Korean(RR) | 목재가숙 휘찬려사(Hwichʻan yŏsa) 범례 | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | History book | |

| Type | ||

| Author(s) | 洪汝河 | |

| Year | mid-17th century | |

| Key Concepts | Historiography, Koryŏ History, International Relations, Sino-Korean Relations, Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | King Kwong Wong | |

| Year | 2018 | |

Introduction

(TBA)

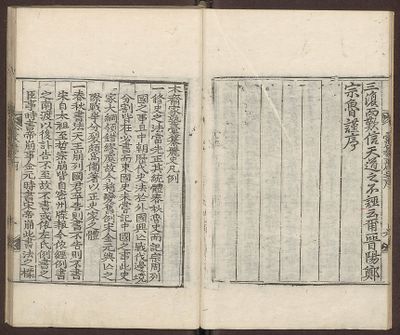

Original Script

| Image | Text | Translation |

|---|---|---|

|

彙纂麗史 凡例

一。春秋書法,天王崩,列國君卒,告則書,不告則不書。宋自太祖至哲宗崩,皆自密州牒報,今依經例書之。南渡以後,訃告不至,故不書,或依左氏例書之。臣事時,書帝崩。事金元時,書宋帝崩。此書法之標 |

Explanatory Notes on the Style and Format of the Compiled Edition of Koryŏ History

One. According to the historiographical principles of the Spring and Autumn [Annals], [the death of] the heavenly sovereign is written as “demised”, and the [death of] various state rulers is written as “deceased”. Whenever [the obituary] was received, then it is written; whenever it was not, then it is not written. During the Song from Taizu (r. 960-976) to Zhezong (r. 1085-1100), the obituary of the emperor all came from the government reports dispatched from Mizhou[1], now following the precedents of the classics I write them. After [the Song] crossed the river south, the obituary did not reach [the Eastern Country], therefore it is not written, or following the example of Mister Zuo[2], it is written. When [the Eastern Country] submitted and served [the Song], [the death of] the emperor is written as “the emperor demised.” When [the Eastern Country] served the Jin and Yuan, [the death of the Song emperor] is written as “the Song emperor demised.” This is the standard of historiographical principles. |

|

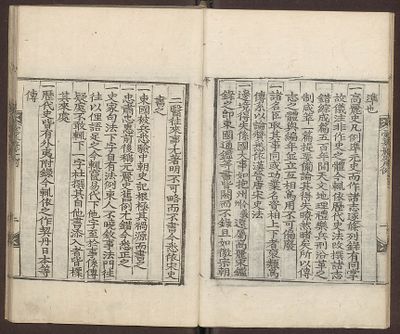

準也。 一。高麗史凡例,準元史而作諸志,逐條列錄,有同掌故儀注,非作史之體。今輒依歷代史法,改撰諸志,錯綜成編。五百年間天文,地理,禮樂,兵刑,沿革之制,咸萃一篇,提要備論,其得失,瞭然睹矣。所以傳志之體,與編年並立,互相爲用,不可偏廢。 一。諸名臣,取其事同或功業名資相上下者,裒類爲傳,糸以論贊。悉依漢,晉,唐,宋史法。 一。邊境得失,係國大事。如抱州今義州,還屬高麗,宋鑑錄之。卽東國通鑑等書,皆闕而不錄。且如徽宗朝二醫往來事,尤著明,不可略而不書。今悉依宋史書之。 一。東國被兵,悉驗中朝史記,根極其禍源而書之。 一。忠肅,忠惠前後稱元,麗史舊例尤錯。今悉正之。 一。史家句法,下字自有法例。東人不曉,敍事法門,往往以俚語足之。今輒竄易,代下他字。至於事係傳疑處,不敢輒下一字杜撰。其自他書添入者,皆標其來處。 一。歷代史,皆有外夷附錄。今輒依之,作契丹,日本等傳。 |

One. As to the style and format of the History of Koryŏ, they follow [the standard of] the History of Yuan for the writing of various treatises. One by one each entry is listed and recorded, like government institutions and ritual protocols; this is not the standard of writing history. Now I imprudently follow the historiographical principles of previous dynasties, alter the composition of various treatises, synthesize the entries into proses. The evolution of the institutions of astronomy, geography, military affairs and punishments during the 500 years are all assembled into proses, so that their summary and entire discourse, as well as advantages and disadvantages, can be observed clear-sightedly. Therefore, the form of biographies and treatises should be established together with the that of chronicle; each makes use of the other. One should not emphasize one form at the expense of another. One. As to the various prominent ministers, take those who had the same affairs or similar achievements, reputations, and backgrounds, put them as group according to their kind to write their biographies, and attach to them my commentaries. All follow the historiographical principles of [the Book of] Han, [the Book of] Jin, [the Book of] Tang, and [the History of] Song.[3] One. The gain and loss of borderland are important affairs that bind the whole state. For example, the return of P'oju (RR: Poju) now Ŭiju (RR: Uiju) to Koryŏ (RR: Goryeo) is recorded in the Mirror of the Song[4]. Even the Comprehensive Mirror of the Eastern Country[5] and the other books, all leave out and do not record it. In addition, cases, such as the two physicians travelled back and forth [between Koryŏ and Song] during the reign of Huizong (r. 1100-1126) are particularly illuminating that cannot be left out and not written. Now following the History of Song all are written. One. As to the wars waged on the Eastern Country, all are verified with the historical records of the central court, tracing the roots of such calamity, and written. One. As to Ch’ungsuk (RR: Chungsuk) and Ch’unghye (RR: Chunghye) proclaimed new reign after each other,[6] the old format of the History of Koryŏ is particularly wrong. Now all are rectified. One. As to the historians’ methods of writing of sentences, the usage of words has its own methods and precedents. People of the East do not know this, and their way of narration often uses unpolished expressions to complete the sentences. Now I imprudently revise and alter them, replacing them with other words. As for the cases that involved places of uncertainty, I dare not imprudently write down a single word to make up. Those of which I added in from other books, all are cited with their origins. One. As to the histories of previous dynasties, all have appendix on foreign barbarians. Now I imprudently follow them and write Kitan, Japan and other biographies. |

|

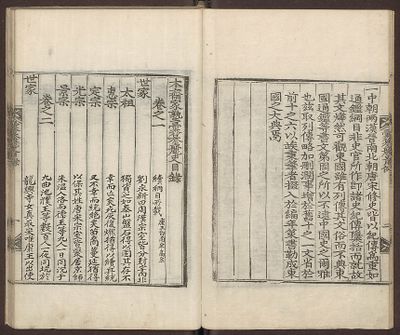

一。中朝兩漢,晉南北朝,唐,宋修史,皆以紀傳爲重。如通鑑綱目,非史官所作,卽諸史紀傳,檃栝而就,故其文燁然可觀。東國雖有列傳,其文俗而不典。東國通鑑等書文,第因之。所以不逮中國史之爾雅也。茲取列傳,略加删潤,事增於舊十之一,文省於前十之六,以俟秉筆者,掇入於編年策書。勒成東國之大典焉。 |

One. The compilations of histories of the central courts – the two Han, the Jin, the North and South dynasties, the Tang, and the Song, all regard highly on the annals and biographies [style]. For example, the Annotated Outline of the Comprehensive Mirror[7] was not composed by court historians, but using the annals and biographies of previous histories as basis, the authors rewrite them for their own convenience, thus its prose is splendid and worth reading. Although the Eastern Country has its own biographies, its proses are vulgar and not elegant. The Comprehensive Mirror of the Eastern Country and other documents one after another follow them. Therefore, they do not reach the refinement of the histories from China. Here I take various biographies and slightly affix my deletion and embellishment: matters are added from the old by one tenth, and words are deleted from the former by six tenths, so as to wait for those who actually write histories to collect and compile it into a chronicle and tighten it up into a great classic of the Eastern Country. |

- Discussion Questions:

- How does Hong Yŏha think about the style and format of the Koryŏsa? What are the reasons for him to justify such changes?

- How does this text reflect the worldview of Chosŏn intellectuals? Considering this text was written in the mid-17th century, how does this text reflect Chosŏn's geopolitical situation of that time?

- What kind of Confucian value is embodied in this text?

- How does this text tell about the author's perception of the Han and non-Han dynasties of China? Why does the author have such perception?

Further Readings

- ↑ nowadays in Shandong province, China

- ↑ This refers to Zuo Qiuming 左丘明 (556-451 BCE), the author of the Zuo Commentary 左傳.

- ↑ The Book of Han 漢書 was written by Ban Gu 班固 (32-92 CE) and completed by Ban Zhao 班昭 (45?-116? CE) during the Eastern Han period (25-220 CE). The Book of Jin 晉書 was compiled by Fang Xuanling 房玄齡 (579-648 CE) in 648. There are two books of Tang – the Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 and the New Book of Tang 新唐書. The Old Book of Tang was compiled by Liu Xu 劉昫 (888–947 CE) in 945 and the New Book of Tang was compiled by Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007-1072 CE) in 1060. The History of Song was compiled by Toqto'a 脫脫 (1314-1356 CE) in 1345.

- ↑ Its alternative title is 增修附註通鑑節要續編. It was compiled by Liu Shan 劉剡 and edited by Zhang Guangqi 張光啓 during Ming Xuanzong’s 宣宗 reign (1426-1435 CE).

- ↑ It was compiled by Sŏ Kŏchŏng 徐居正 (RR: Seo Geojeong, 1420-1492 CE) and completed in 1485.

- ↑ This refers to the fact that they consecutively succeeded each other, thus both had a second ascension after the other’s dethronement.

- ↑ It was compiled by Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130-1200 CE) and is the first kangmok style history of its kind.