Property Distribution Record from the Meeting of the Hach'an-siblings

| Primary Document | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | |

| English | Property Distribution Record from the Meeting of the Hach'an-siblings |

| Chinese | 河鑽娚妹和會文記 |

| Korean | 1757년 하찬 남매 화회문기 |

| Document Details | |

| Genre | Social Life and Economic Strategies |

| Type | Record |

| Author(s) | Ha Ch’an |

| Year | 1757 |

| Key Concepts | |

| Translation Info | |

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2016 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) |

| Editor(s) | (Introduction) Jamie Jungmin Yoo |

| Year | 2016 |

Introduction

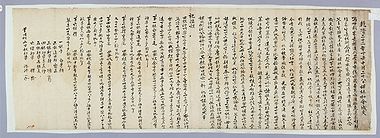

“Punjaegi (property distribution records, 分財記)” is a generic term for inheritance documents in Chosŏn. Depending on the contents, this body of texts had many different titles; for example, “hwahoemun’gi (和會文記)” for the property distribution among siblings, or “pyŏlgŭpsŏngmun (別給成文)” for inheritance to those who had special merits. The “Property Distribution Record from the Meeting of the Ha Ch'an-siblings (河鑽娚妹和會文記, 1757; hereafter the Record)” was made by Ha Ch’an (1737 - 1800) and his siblings for the purpose of distributing the property of their late father, Ha Chae-ak (河載岳). Ha Chae-ak was survived by a son and five daughters.

In general, “hwahoemun’gi” was created after the three-year mourning period. When drafting the document, all children of the deceased father were required to attend the meeting and agree to the final settlements of the distribution. In order to avoid any future conflict or misunderstanding, all participants signed at the end of the document, which is called sŏap (暑押).”[1] The Record by Ha Ch’an also contains the signatures of his family members at the end.

Looking closer, however, the Record did not list the names of the daughters at all, only mentioning their husbands.[2] Moreover, out of five daughters and their husbands, only Han Yong (韓墉), the husband of the third daughter, attended the meeting. Therefore, the Record contains only two “sŏap” signatures made by Han Yong and Ha Ch’an who had organized the meeting. If this is the case, did the low attendance of the family members have any specific meaning?

According to the Record, Ha Ch’an, the only son of the family, sent out letters of invitation to convene the gathering. Except for Han Yong, all recipients stated a reason for not being able to attend. Their reluctance toward attending the meeting can be explained in terms of the inheritance law in late Chosŏn. After the mid-17th century, the firstborn son began to acquire the privilege of primogeniture, and consequent actual inheritance practices reduced or ruled out the rights of daughters. [3] The total absence of women’s voices in the Ha Ch’an Record presented a great contrast to other inheritance documents from earlier periods. Assured by equal distribution law, the life and social status of female participants are vividly exposed in many inheritance records from early Chosŏn. From the body of “punjaegi” texts, we find valuable sources for the study of Chosŏn society, particularly in terms of legal regulations, actual practices, and how these shifted with the times.

Primary Source Text

| English | Classical Chinese |

|---|---|

|

Qianlong, the 22nd Year Chŏngch'uk (1757), 10th Month, 28th Day, Record for the property distribution among brothers and sisters. Oh! Our family has repeatedly suffered deaths and disasters over several generations. When I was no more than six years of age, I suddenly lost my father. All alone and desperate to no end, I bade our relatives farewell and left our family home to grow up in a different village. Now I have taken a wife and inherited family property. [Yet] my heart cannot harbour my sorrow, how can it bear these words? I silently remember the times when our father was alive and the matters he could not take care of. Now has come the time when we cannot but convene as siblings to distribute the family property in writing. For this to do after my relatives return, I have written letters and sent them to my sisters houses. However, the first sister and her husband have both passed away. Although they have a son and a daughter, the son is still young and the girl is already married, so they were not able to participate. The second brother-in-law had to perform sacrificial rites in his family and therefore wrote back to me that he was not able to attend. The fourth brother-in-law had a funeral and could not come. The fifth brother-in-law lived a thousand li away (or very far away), and also had a funeral in his family so that he could not attend. So the participants [in this] were a few people from our family and the third brother-in-law, named Han Yong. In the old days, of what was left after death and disaster, over generations the lands for the sacrificial rites were sold away in large portions. Therefore my grandfather left his will to my late father urging him to do his utmost to supplement this lacking number. However, my father passing away at young age did not get to supplement it. Now, on this day of creating this document, the descendants from various branches, to restore the original amount of shrine land decided on fourth generations ago, should investigate into my father’s inherited share [of land] and the paddies he bought, to make up for the reduced sum of shrine land due to it being sold away over the generations. When my late father was still alive, respecting the will of my grandfather, one sŏk of fields and six tu of paddies were given away to distant uncles that had no descendants, and his step-brothers were given their share of 11 tu of paddies and 7 tu of fields. Also land for the upkeep of the tombs was given in the will and then taken out of share of my late father. This was deduced by the descendants and according to the will land for the tombs was provided. Concerning the twenty-two tu of paddy fields in Oridongwŏn, Komodongwŏn, Kaejŏnwŏn, Kajŏngjawŏn, Masanwŏn, and Yangmogwŏn, they are only recorded in the draft land register, but lacking the detailed location, so no more can be determined. The remaining land includes sixteen tu and five to of paddy fields and two sŏk and nine tu of dry fields. The land for the sacrificial rites for our parents is determined following public opinion (general practice) and based on the legal code. The remaining lands are distributed equally among the six siblings. The slaves, in the written will of my deceased grandfather it states, are all part of the property for the sacrificial rites and later generations cannot bring this up for discussion. For this reason, when my late father married off my first- and second-born sisters, he did not give either of them any new slaves, but each was given the money for buying female slaves. As for my third- and fourth-born sisters, our mother, based on this regulation, gave them each the means to purchase a female slave. As for my sister in Kwangju, she got married into a family far away and to send her away without a slave would have been heartless, therefore only for her a slave named Wŏndŏk, the fourth-born slave of a purchased slave called Yidan, was bought. Then, I took Wŏnsim, one of five slaves born to the purchased slave. Thus, according to the precedent that some of my sisters received money and others took slaves, and following the public opinion (general practice), I took my share. And for the remaining four slaves, they are to be set aside for the new land for the upkeep of the shrine. These matters were discussed and decided and this document was composed. |

乾隆二十二年丁丑十月二十八日娚妹和會成文 嗚呼! 我家喪禍連代疊出, 年纔以六歲, 奄失所怙, 孤危莫甚, 辭親離家, 生長他鄕. 今始入娶承家, 感愴莫逮之懷, 曷勝言哉! 窃念父主生時, 其未區處, 則娚妹和會文字, 不可不及時, 玆於眷歸之後, 相欲成文裁書, 偏通諸妹家 而第一妹內外俱沒, 雖有一男一女, 男幼女嫁未參焉. 第二妹夫則以祀故答書而未參焉. 第四妹夫則以喪身未參焉. 第五妹夫則遠在千里, 且以喪身未參. 所與參同者, 本族諸人, 及第三妹夫韓墉也. 第惟在昔喪禍之餘, 連代祀位, 曾多放買, 故祖父主遺書於我先考, "使之竭力充補其賣數," 而袞我先考, 靑年謝世, 未及充補矣. 今當成文之日, 支孫諸人歸重祀位, 四代元定數, 推尋先考衿得, 及買得畓充補, 連代祀位放賣減縮之數, 先考在世時, 又遵祖父主遺書, 田一石地及畓六斗地, 出給庶叔無后, 支庶衿付畓十一斗地田七斗地, 亦有付墓位之遺書, 而疊入於先考衿下, 諸孫亦爲推出, 依遺書付墓位, 吾里洞員·古毛洞員·介田員·假亭子員·馬山員·若木員, 合畓二十二斗地段, 只錄於田畓草記, 不書第坐卜數, 故未能推尋. 餘存畓十六斗五刀地, 田二石九斗地也. 父母主祀位, 從公論, 依法典, 定出; 其餘田畓, 六娚妹平均分衿; 奴婢段, 祖父主遺書中, 皆是 祀位, 後世子孫元不擧論云, 故父主在世時, 嫁送第一第二妹, 而皆未給新婢, 各以買婢價給之. 第三第四妹, 則母主亦, 以此規, 各給買婢價, 廣州妹, 則千里遠嫁, 無婢送去, 情理切迫, 故獨給買得婢以丹四所生婢遠德, 而買得婢所生五口內遠心一口, 則依諸妹或捧價或率婢之例, 從公論, 衿付於余, 其餘四口段, 亦以新祀位議定成文事. |

Discussion Questions

- Why were the invited people unable to attend the family meeting? Do you think the reasons given are true? How does gender figure into the division of property?

- How does it compare to other documents that deal with the division and management of property in Chosŏn Korea?

- Should we view the shrine land as communal or as private? Why was it important to set aside property for sacrificial rites? How does it inform our understanding of Chosŏn as a “Confucianizied” society?

Further Readings

References

- ↑ Changsŏgak, Chosŏn Sidae Chaesan Sangsok Munsŏ Punjaegi: Kongjŏng Kwa Hamniŭi Changŭl Toejipŏ Poda (Records of property inheritance of Joseon-retracing the page of justice and rationality), ed. Ŭn-mi Ha and In-hwan No (Kyŏnggi-do Sŏngnam-si: Han’gukhak Chungang Yŏn’guwŏn, 2014), 248 – 249.

- ↑ http://goo.gl/R2h7Q7 (accessed July 22, 2016)

- ↑ Pyŏng-kyu Son, “Chosŏnhugi Sangsokkwa Kajokhyŏngt’aeŭi Pyŏnhwa 조선후기 상속과 가족형태의 변화,” Taedongmunhwa Yŏn’gu 대동문화연구 61 (2008): 375–404.