(Translation) 麗史提綱

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | Yŏsa Chegang | |

| Chinese | 麗史提綱 | |

| Korean(RR) | 여사제강 | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Old Books (古書) | |

| Type | History 歷史書 | |

| Author(s) | 兪棨 | |

| Year | 1667 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | History | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | King Kwong Wong Participants of 2017 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | King Kwong Wong | |

| Year | 2017 | |

Introduction

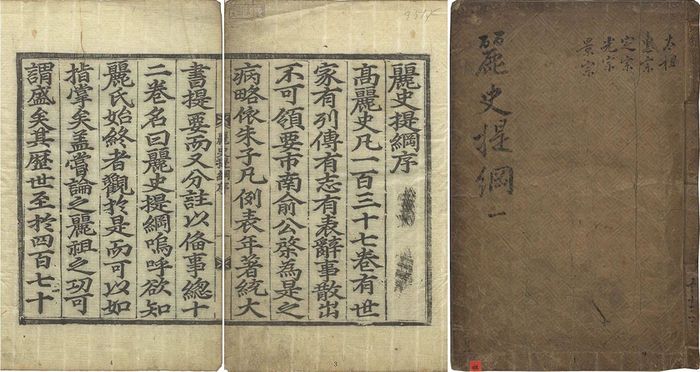

The Yŏsa chegang 麗史提綱 (the Annotated Outline of Koryŏ History), compiled by Yu Kye 兪棨 (1607-1664), was published in 1667, three years after the compiler’s death. It seems, according to the preface written by Song Si-yŏl 宋時烈 (1607-1689), Yu Kye was unable to publish the history book before he died, and so he helped the publication. The history book has a total of 23 volumes, covering the history of Koryŏ from the beginning of T’aejo 太祖’s reign (r. 918-943) to the reign of King Ch’ang 昌王 (r. 1388-1389). Interestingly, the reign of King Kongyang 恭讓王 (r.1389-1392) is left out from this history. As the preface and explanatory notes state, the historiographical genre of the book follows that of Zhu Xi朱熹 (1130-1200)’s Zizhi tongjian gangmu 資治通鑑綱目 (the Annotated Outline of the Comprehensive Mirror) – the kangmok 綱目 (Ch. gangmu, annotated outline).

With the rising prominence of Confucian-minded literati at the court, the Chosŏn state (1392-1910) put great emphasis on the writing of history. As early as the beginning of the dynasty, the state had already commissioned several historical texts, notably: the Koryŏsa 高麗史 (the History of Koryŏ) in 1451, the Koryŏsa chŏryo 高麗史節要 (Essentials of Koryŏ History) in 1452, and in 1486 the Tongguk t’onggam 東國通鑑 (the Comprehensive Mirror of the Eastern Country), which was modeled on the Northern Song historian Sima Guang 司馬光 (1019-1086)’s Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑑 (the Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Governance).[1] Beside the state-endorsed historical works, a new historiographical trend began to develop in the sixteenth century. Private compilation of history, such as Pak Sang 朴祥 (1474-1530)’s Tongguk saryak 東國史略 (the Abridged History of the Eastern Country) and O Un 吳澐 (1540-1617)’s Tongsa ch'anyo 東史纂要 (the Compendium of the History of the East) marked this trend. And along this trend was the rise of Zhu Xi’s historiography starting from the seventeenth century.[2]

The Yŏsa chegang, thus, can be seen as a product of the historiographical development in the Chosŏn period. But more importantly, what underlay this historical trend was the Confucian view of history. Particularly, the praise and criticism on the kings and officials of the Tongguk t’onggam reflects the Neo-Confucian historiography that influenced later historical writings, including Yu Kye’s own Yŏsa chegang.[3] As he explains it in the explanatory notes, Yu Kye, however, used another form of historiography that was advocated by the Neo-Confucian Zhu Xi to advance his Neo-Confucian view of history. But this change of using a different historical genre had no bearing on the general Confucian view of history as he retains the praise and criticism of his predecessors. Furthermore, the various comments made by Song Si-yŏl in his preface regarding the downfall of the Koryŏ dynasty also reflect his Neo-Confucian view of history.

One of the reasons that Yu Kye disregarded the previous t’onggam historiographical genre when compiling the Yŏsa chegang was to facilitate the study of history. In this regard, it seems he was successful as later King Yŏngjo 英祖 (r. 1774-1776) studied it in his royal lectures, although it was not presented to the monarch during his lifetime.[4] The list of historical works that the monarch read included some of the t’onggam and kangmok works mentioned above, alongside with other Confucian classics.[5] The study of history, particularly the Neo-Confucian vision of history, was thus essential to the upbringing of the monarch as the case of Yŏngjo shows.

Since historical learning had a major bearing on the monarch, it was Song Si-yŏl’s imperative to recommend Yu Kye’s historical work to be presented to the Chosŏn king. Aside from this reason, Song Si-yŏl’s preface also reveals his political stance in the interstate relations between Chosŏn and the Qing dynasty (1636-1912). In the preface, he expresses his disgust to the marriage between Koryŏ and the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), and at the same time his approval to the relations between Koryŏ and the Song dynasty (960-1276). This can be seen as a parallel of the struggle between the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the Manchus, and Chosŏn in Northeast Asia in the early seventeenth century as the situations then were similar: the Koryŏ-Song relations symbolize the Chosŏn-Ming while the Koryŏ-Yuan relations symbolize the Chosŏn-Qing. Considering the fact that Song Si-yŏl was a hardliner of pro-Ming policy in the Chosŏn court throughout his official career and that the last Manchu invasion was merely 30 years prior to the publication, anti-Qing sentiment remained prominent in the court albeit the Ming was destroyed 23 years ago. Therefore Song Si-yŏl’s comment in the preface is politically charged as he hoped that unlike the late Koryŏ which sided with the Yuan, the Chosŏn state should follow the example of early Koryŏ, upholding the moral principle – an essential concept of Neo-Confucianism.

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

麗史提綱 序

|

Preface of the Annotated Outline of Koryŏ History

|

|

麗史提綱 凡例

麗史蓋倣歷代全史之體,故其世家則只載年月綱領而已。其餘國政沿革人物出處可鑑可戒者,皆散在雜志列傳之中。學者乍見漫不省,先後次序雖曰一書而其實三書也。且卷秩甚多,披覽未半,輒至厭倦,吳氏澐爲是之病作纂要以便觀覽,而但紀年則所戴太略事實之可攷者,盡在列傳,是亦未免一冊而二書,參考之難猶夫前也。通鑑雖湊合成書而既無綱目之別、編年之次,觀者亦無以挈其綱要。今姑取麗史世家綱領及諸書特,筆者為之綱,旁搜列傳雜志及諸書中事迹,以為目,而分注其下。雖世家所不載而必當立綱處,則亦別立綱而注其事。至於筆法褒眨,則略倣舊史不敢以妄意多所增損。 本國雖歲奉中國正朔,而此書乃本國私紀,故以本國紀年而分注中國年號於其下。且書甲子於逐年之上行外以表之。無取其見於宋史者以訂其異同。 此書雖起自麗祖之即位,而當時新羅、百濟尚存,故麗祖統合以前,則用綱目無統例列書三國於甲子下。但麗濟皆本於羅,故略用君臣之例。 編年之際、或春無可紀之事,則首書夏夏秋冬亦然。若一年全無可紀之事,則袛書年以表之而已,不敢依春秋。雖無事而必書春秋以成歲之例。 凡一歲中但用月分編窆而已,不敢用春秋以日紀事之例。 凡注事於綱領之下,皆旁搜諸書考訂日月。至於日月不可考而事不可不紀者,及人物行迹相隣而無甚異同者,則不立綱而只以類附見焉。 凡列傳雜志中但紀其年而無日月可考者,則不得已於逐年之末立綱以見焉。 凡稱宗,稱陛下、太后、太子、節日詔制之類,雖涉僣偽,今不可盡行刪削,故只仍當時所稱。 禑昌紀年只仍吳氏纂要之例,不敢有所改易。 凡事大交隣、朝聘往來,雖煩必書。天灾時變雖不可盡書,而如日食、地震、彗孛、飛流之類,雖煩必書。至於星辰晝見風雷霜雹人妖物恠等,則只書其特異者焉。 如燃燈八關醮祀等事,及其餘歷代例行而不可盡紀者,則只於始見處並著其首末。 凡事有相連不可分紀者,則或於首起處終言之,使無散漫。 凡除拜國相,雖煩必書。如君子小人表表用舍之處,則雖非相職亦書。 凡人物事迹隨事編摩,而其有遺漏者,則收入於書卒之下。 凡官制沿革各隨當時所稱而書之。 凡州縣名號各注今名於其下,而不可考者則闕之。 凡讖緯不經荒誕鄙俗之說,今皆刪去,衹存其近實者。 凡有可疑不可為典要者,則分注錄之,以附傳疑之義。 凡諸書中先儒及史家評論間取而芟載之。當時史官則稱史臣,後日撰史時諸臣則稱史氏。若其人姓名可考者,則皆書某氏某。 凡文字艱澁難有差謬可疑處,不敢輒改並仍其舊。 凡附愚見處,則以按字別之,而圈其上。 |

Explanatory Notes on the Usage of the Annotated Outline of Koryŏ History

The History of Koryŏ[22] imitates the style of previous dynastic histories, thus its annals only record the gist of years and months. The rest – the development of state affairs and the appointment and retirement of personalities – which are worthy to reflect upon and to heed as admonishment, are all scattered amid various treatises and biographies. Scholars, at first glance, see [them] all over the place; it is not easy [to read]. Although the sequence [of events] is said to be [contained] in a book, in fact, it is in three. In addition, the number of volume is too many. Perusing not even half of the content, [one] often already feels disgusted and weary. Because of this shortcoming, Mister O Un wrote the Compendium[23], so as to facilitate the observation and reading [of histories]. However, the passages recorded in the annals are too brief, and the verifiable facts are all recorded in the biographies. Thence, it cannot escape [the shortcoming of] being a volume and yet two forms of writing. The difficulty to examine and study [histories] resembles the former. Although the Comprehensive Mirror[24] gathers together histories in one book, it neither distinguishes between the key points and details nor has the order of annals. Readers thus have no way to grasp its essence. Now the author tentatively took the essence of the History of Koryŏ and various books as outlines, and widely searched through the biographies and various treatises for facts and deeds as details, which were separately annotated underneath the outlines. Although they are not recorded in the annals, for those which should be established as outlines, outlines were separately established and annotated. As for writing the judgment of praise and criticism, the author roughly imitates histories of the past and dares not rashly subjoin or reduce. Our country although yearly receives the calendar from the Middle Kingdom, since this book is private annals of our country, the year of our country was thus written and the reign title of the Middle Kingdom was annotated underneath. Besides, the kapcha sixty-year cycle was written and displayed above each year, outside of the column. Views from the History of the Song were not taken so as to discern the differences and similarities. Although this book starts from the enthronement of Koryŏ T'aejo, since at that time Silla and Paekche still existed, for this reason before T'aejo of Koryŏ united the country, the rule of non-unification from the kangmok[25] was used to list the Three Kingdoms under the sixty-year cycle. However, Koryŏ and Paekche were originated from Silla, hence the regulation of ruler and ministers was roughly used. In between the years, or if there was nothing to record in Spring, then [the event of] Summer is first written, if not, Autumn, and then Winter. If a year did not have anything to record, then only the year was written to display it. The author dared not follow the Spring and Autumn [Annals] - even if there was no affair, Spring and Autumn were written to display the year. For each year, the events were only separated and chronicled monthly, and the author dared not use the standard of the Spring and Autumn to record events daily. For the annotations under the outlines, all were widely investigated from various documents to revise their month and day. As for those which cannot be left unrecorded and yet their dates cannot be verified, as well as those recording personalities whose deeds were similar and adjacent to each other, then outlines were not established but their kinds are grouped so that they can be viewed [together]. For those of which only their years were recorded in biographies and various treatises, and their dates cannot be verified, then outlines were established at the end of each year so that they can be seen. Whenever the king’s temple name contains chong, he was addressed as Your Majesty, [his mother] queen dowager, [his heir apparent] crown prince, [his birthday] festival, [his instruction] decree, and so on. Although these amount to usurpation, now they cannot be totally erased, so their names at that time were kept. For the annals of [King] U and [King] Ch'ang, the author only followed the example of Mister O’s Compendium and dared not have any alterations and changes. For [the events related to] “serving the great” and amicable diplomacy with neighbors, and the reception and dispatch of diplomatic envoys even they are trivial, all were recorded. Not all natural disasters and change of time were written. Yet for those like solar eclipse, earthquake, and flying of comets, albeit trivial all were recorded. As for sighting of constellation during daytime, gale, thunder, frost and hail, human demons and supernatural spirits, and so on, only those which were peculiar and distinctive are written. For yŏndŭng and p’algwan,[26] as well as sacrificial offerings and the rest of the routines of the past dynasties which cannot be all recorded, their courses of event were recorded only on their first appearance. For the events which were linked together and cannot be separated in different annals, then their conclusions were written at where they are started, so that they are not scattered. For the dismissal and appointment of prime minister, albeit trivial all were recorded. As for the occasion where the honorable men and lesser men were distinctively appointed or retired, even their posts were not comparable to that of the prime minister, they were recorded. For personalities and their deeds, all were compiled according to the events. As for those that were left out, then they were collected at the end of the book. For the development of the official institution, all were written according to their names at that time. For the names of county and prefecture, all were annotated with their current name underneath. As for those which cannot be verified, they are omitted. For divinations and abnormal, ridiculous and vulgar speeches, all were now removed. Only those which were close to the reality were kept. For those dubious occasion which cannot become the standard, all were separated in annotation, so as to attach the meaning of doubt. For the comments of previous Confucians and historians amid various documents, all were selected, weeded out and recorded. Court historiographer at that time are called official historian, the various officials of later period who authored histories are called mister historian. If their names are verifiable, they were all written in this format: Mister, their family names, then followed by their personal names. Whenever the words are difficult and obscure, which hardly have any erroneous and questionable occasions, the author dared not absurdly alter and thus keep them in their original. Whenever the author attached his humble opinions, they were marked by the character an with a circle above. |

- Discussion Questions:

Further Readings

Ch'oe Yong-ho. “An Outline History of Korean Historiography.” Korean Studies 4 (1980): 1-27.

Chŏng Ku-bok. “Traditional Historical Consciousness and Historiography.” In Introduction to Korean Studies. Seoul: The National Academy of Sciences, 1986.

Haboush, JaHyun Kim. “Confucian Rhetoric and Ritual as Techniques of Political Dominance: Yŏngjo's Use of the Royal Lecture.” The Journal of Korean Studies 5 (1984): 39-62.

Zhu Xi. Chachʻi tʻonggam kangmok 資治通鑑綱目. Seoul: Pogyŏng Munhwasa, 1987.

- ↑ Ch'oe, “An Outline History of Korean Historiography,” 11.

- ↑ Chŏng, “Traditional Historical Consciousness and Historiography,” 131-132.

- ↑ Ibid., 129.

- ↑ Haboush, “Confucian Rhetoric and Ritual,” 59.

- ↑ Ibid., 55-59.

- ↑ Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130-1200), one of the founding fathers of the Neo-Confucian school in the late Southern Song period.

- ↑ Refers to King Ch’ungsŏn 忠宣王 (r. 1298, 1308-1313) and King Ch’unghye 忠惠王 (r. 1330-1332, 1339-1344), who were respectively the second and the fourth king married a Mongol princess.

- ↑ This is a sign from the Book of Change 易經 (Yijing), Hexagram 16, Yin in Fifth Place. Zhu Xi comments on the sign as follows: the chronic illness means the state of being in the danger of indulging pleasure by a false sense of elation, and yet by remaining steadfast at the center one survives. See Zhu Xi, Zhouyi benyi 周易本義 (the Original Meaning of the Book of Change).

- ↑ Jieyang is in nowadays eastern part of Guangdong province of China.

- ↑ Wen was the posthumous appellation of Han Yu 韓愈 (768-824), a poet and official of the Tang dynasty (618-907).

- ↑ This refers to Han Yu’s exile to Chaozhou 潮州 in 819, see his work “Stele of Huangling Temple 黃陵廟碑.” Han Yu was twice exiled to Guangdong and left a couple of works expressing his distaste of this region.

- ↑ This refers to King Ch’unghye’s banishment by the Yuan in 1344.

- ↑ This refers to King Ch’ungsŏn’s exile between 1320 and 1324. See also Yŏsa chegang’s entry at Chapter 18 “忠惠王後紀 四年十二月” for a similar commentary on Ch’ungsŏn’s and Ch’unghye’s exiles.

- ↑ Ikchae was Yi Che-hyŏn 李齊賢 (1287-1367)’s pen name.

- ↑ P'oŭn was Chŏng Mong-ju 鄭夢周 (1337-1392)’s pen name.

- ↑ This refers to Zhu Xi’s comment in his preface of Zizhi tongjian gangmu 資治通鑑綱目 (the Annotated Outline of the Comprehensive Mirror).

- ↑ Sima Guang 司馬光 (1019-1086), a politician and historian of the Northern Song period (960-1127).

- ↑ This is Sima Qian’s 司馬遷 (c. 145-86 BCE) comment on Xunzi’s 荀子 (c. 313-238 BCE) idea of “following rulers of later generations.” See Shiji 史記, Chapter 15.

- ↑ Nowadays Fujian province of China. Zhu Xi was born in the Min region and served as an official there.

- ↑ Chongzhen (r. 1627-1644) was the reign title of the last Ming (1368-1644) emperor. The Chosŏn (1392-1910) state still used the Ming reign title to record time even after the Ming fell in 1644.

- ↑ Samguk sagi 三國史記

- ↑ Koryŏsa 高麗史

- ↑ O Un 吳澐 (1540-1617) completed Tongsa ch'anyo 東史纂要 (Compendium of the History of the East) in 1606.

- ↑ Tongguk T’onggum 東國通鑑 (Comprehensive Mirror of the Eastern Country)

- ↑ Kangmok 綱目 (annotated outline), a genre of historical writing.

- ↑ Both Buddhist ceremonies, respectively the Festival of Lotus Lantern and the Festival of Eight Precepts.