(Translation) 李珥 箕子實記

| Primary Document | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | The True Record of Kija | |

| Chinese | 箕子實記 | |

| Korean(RR) | 기자실기(Kijashilgi) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | ||

| Type | ||

| Author(s) | 李珥 | |

| Year | 1580 | |

| Key Concepts | China-Korea relations, Neo-Confucianism | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | Inho Choi | |

| Year | 2018 | |

Introduction

The True Record of Kija was written by the famous Korean Neo-Confucian scholar I I(李珥). The story of Kija is recurrent topic in the Korean writings, and there has been a religious worship of Kija since the three dynasty period. Although it has never been a major literary theme, it has a unique importance since it forms a long-standing coherent literary unit that is reflective of the changing Korean relationship with the political entities in China. By tracing its transmission and changes, it is possible to grasp the historical transformations of the changing Sino-Korean relationship. It was Shiji that first records Kija's eastward coming to Chosŏn. It tells King Wu of Zhou enfeoffed him to Chosŏn. In Korean writings, this story first appears in the early Koryŏ period.

Based on the research by Han Yŏngu,[1] we can reconstruct three phases of Kija story. In the first phase that ended around the Shilla-Koryŏ transition, Kija was deemed as one of the ancestral gods of the Korean country rather than a vassal enfeoffed by a Chinese emperor. This story of Kija transformed significantly in the process of the newly found Koryŏ's negotiation with China. This is the second phase. The Chinese states wanted to emphasize the story that Kija was a Chinese vassal and that his role was mainly to transmit the advanced Chinese culture to Korea. Koryŏ court partially accepted this view and treated Kija as the teacher of ritual and moral edification. The third phase is concurrent with the influx of the Neo-Confucian thoughts. Starting with the Songs of Emperors and Kings(帝王韻紀) by I Sŭnghyu, it was emphasized that Kija told the Great Plan with Nine Principles(洪範九疇) to King Wu. This new element of universal principles opened up a interpretive space.

I I's version of story is situated in this last phase, and yet he adds his own unique features by making use of the interpretive space opened up by the new Neo-Confucian discourse. We can discern at least three important changes that I I makes. First, I I makes it clear that to become a ruler either in China and Korea one should be a sage or be thought by a sage. Kija's role now becomes a teacher of Neo-Confucian sagely teaching. He is the one who embodies the way of Sage(身傳聖道), and he is the King-Teacher(君師)of Korea, the ideal model of the Neo-Confucian kingship.[2] King Wu himself was somewhat lost(he had to ask Kija whether his rebellion was justifiable), and becomes whole only after he was given the teaching of the Great Plan with Nine Principles. He even had to empty his self(虛己) before asking Kija.

Second the role of Chosŏn as an equal partner in ordering the world is established in his version. Kija becomes a pivot in this partnership. I I says, "Majestic! You Kija. Having already laid out the Great Plan to King Wu so that the Way became bright in China, you inferred those that still remains unfulfilled and made the transformative government to be abundant in the Three Hans(三韓).[3] In the latter part of the account, Kija also becomes a beginning of another genealogical line of the Way learning on par with the Neo-Confucian founders such as Zhu Xi.

Third, through figuring an emotional account of King Wu's relationship with Kija, I I creates a communicative depth between the Chinese King and the Korean sage. This feature is very unique to I I's version and did not appear in the previous version. For example, the way he describes Kija' enfeoffment even supposes a communicative empathy between them that even surpasses linguistic exchange. King Wu "empties his self and inquired about that because of which the Yin had been ruined. He said, "My killing of Zhou, was it right or wrong?" Kija could not bear to say. The King then inquired about the Way of Heaven." Here, Kija provoke King Wu to ask about the Great Plan by not saying anything to King Wu. Also, after answering King Wu's question, Kija "did not want to serve in his court. King Wu, too, did not dare to force him." We do not know whether there was actual verbal exchange. However, the figurative effect of I I's account creates the impression of emphatic understanding. Kija did not 'want' to serve, and King Wu, 'too(亦),' somehow felt this desire and therefore did not 'dare(敢)' to forced him. This empathetic depth is something unseen in the previous account of the same interaction. For example, in his account of the same exchange, King Sejong simply says that King Wu followed Kija's will(志). The rich emphatic interaction disappears in this version. We have no clue whether King Wu's decision was a result of his sympathy toward Kija's feeling or he just had to yield to Kija's strong will. This strong emphatic understanding was perhaps never realized in the actual diplomacy between Ming China and Chosŏn. However, by rendering the story of Kija this way, I I at least provided a new ideal for Chosŏn diplomats to pursue vis-à-vis China.

Original Script

| Image | Text | translation |

|---|---|---|

|

箕子實記

|

translation |

|

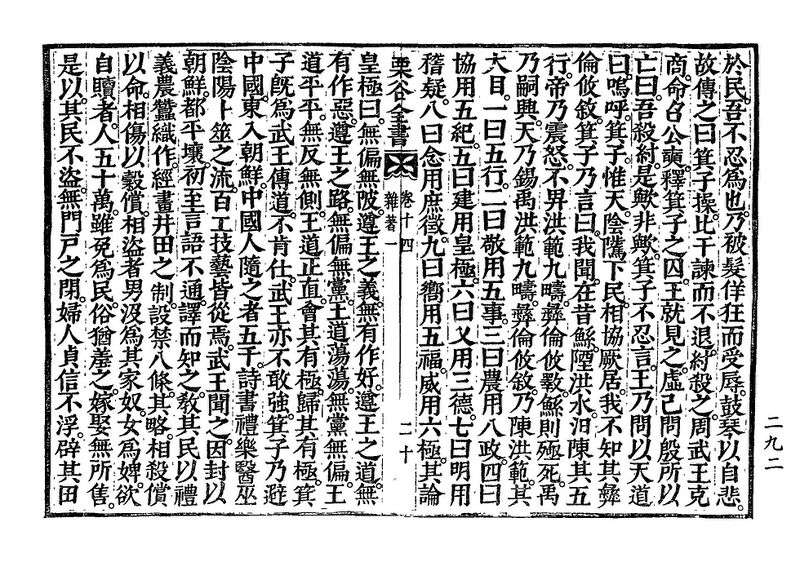

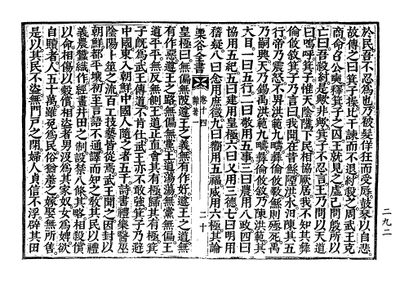

吾不忍爲也。乃被髮伴狂而受辱。鼓琴以自悲。故傳之曰箕子操。比干諫而不退。紂殺之。周武王克商。命召公奭。釋箕子之囚。王就見之。虛己問殷所以亡曰。吾殺紂。是歟非歟。箕子不忍言。王乃問以天道曰。嗚呼。箕子。惟天。陰騭下民。相協厥居。我不知其彝倫攸敍。箕子乃言曰。我聞。在昔鯀。陻洪水。汩陳其五行。帝乃震怒。不畀洪範九疇。彝倫攸斁。鯀則殛死。禹乃嗣興。天乃錫禹洪範九疇。彝倫攸敍。乃陳洪範。其大目。一曰五行。二曰敬用五事。三曰農用八政。四曰協用五紀。五曰建用皇極。六曰乂用三德。七曰明用稽疑。八曰念用庶徵。九曰嚮用五福。威用六極。其論皇極曰。無偏無陂。遵王之義。無有作好。遵王之道。無有作惡。遵王之路。無偏無黨。王道蕩蕩。無黨無偏。王道平平。無反無側。王道正直。會其有極。歸其有極。箕子旣爲武王傳道。不肯仕。武王亦不敢强。箕子乃避中國。東入朝鮮。中國人隨之者五千。詩書禮樂醫巫陰陽卜筮之流。百工技藝皆從焉。武王聞之。因封以朝鮮。都平壤。初至言語不通。譯而知之。敎其民以禮義農蠶織作。經畫井田之制。設禁八條。其略。相殺償以命。相傷以穀償。相盜者男沒爲其家奴。女爲婢。欲自贖者。人五十萬。雖免爲民。俗猶羞之。嫁娶無所售。是以。其民不盜。無門戶之閉。婦人貞信不浮辟。 |

... King Wu of the Zhou conquered the Shang, and order Shaogongshi(召公奭) to release Kija. The King proceeded to see him. He empties his self and inquired about that because of which the Yin had been ruined. He said, "My killing of Zhou, was it right or wrong?" Kija could not bear to say. The King then inquired about the Way of Heaven. He said, "Oh! count of Qi, Heaven, (working) unseen, secures the tranquillity of the lower people, aiding them to be in harmony with their condition. I do not know how the unvarying principles (of its method in doing so) should be set forth in due order." The count of Qi thereupon replied, "I have heard that in old time Gun dammed up the inundating waters, and thereby threw into disorder the arrangement of the five elements. God was consequently roused to anger, and did not give him the Great Plan with its nine divisions, and thus the unvarying principles (of Heaven's method) were allowed to go to ruin. Gun was therefore kept a prisoner till his death, and his son Yu rose up (and entered on the same undertaking). To him Heaven gave the Great Plan with its nine divisions, and the unvarying principles (of its method) were set forth in their due order."[4] Then, he explained the Great Plan(洪範). The main items are the following. The first is called Five Phases(五行). The second is to use five matters for reverence. The third is to use eight policies for agriculture. The forth is to use five cosmological cycles for cooperation. The fifth is to use the standard of the imperial greatness. The sixth is to use three virtues for governing. The seventh is to use reflection for clarity. The eighth is to use timely order for thought. The ninth is to use five fortunes for pleasure and to use six misfortunes for awe. As for the discussion on the imperial greatness(皇極), it says There shall be no being decentered and no being uneven and respect the righteousness of King. There shall be no personal liking and follow the way of King. There shall be no personal disliking and follow the path of King. There shall be no being decentered and no taking side, and the way of King will be broad and expansive. There shall be no taking side and no being decentered, and the way of King will be even and fair. There shall be no violation of principle and no incorrection, and the way of the king will be straight. When gathering subjects, there must be a standard. When returning to the lord, there must be a standard. Kija had already transmitted the Way for the sake of King Wu and did not want to serve in his court. King Wu, too, did not dare to force him. Kija, then, avoided the central country and came eastward to Chosŏn. Those Chinese who followed him were five thousand. They were the kinds who deal with Songs, Books, Rituals, Music, Medicine, Worship, Yin and Yang, and Prognostication. The artisans and artists of numerous kinds all followed him. King Wu heard of this, and enfeoffed him with Chosŏn. He set up his capital at P'yŏngyang. When he first arrived, languages did not fit. He understood the native language through translation. He edified that people with rituals and righteousness and with agriculture, sericulture, weaving, and craft and instituted the well-filed demarcation. He laid out the articles of eight prohibitions。Those who kill people shall recompense with their life. Those who hurt others shall recompense with their crops. Those who steal from a house shall be deprived and become male slaves of that house. Women shall become female slaves. [Among the thieves,] those who want surrender themselves to the justice have to pay five hundred thousand [unit missing]. Although they avoid being enslaved and remain as commoners, the custom deemed it to be shameful. The marriage arrangement had no those that by which one can be sold and bought. Hence, that people had no stealing and no closing of house doors. The wives were straight and faithful, and were not careless and partial.

|

|

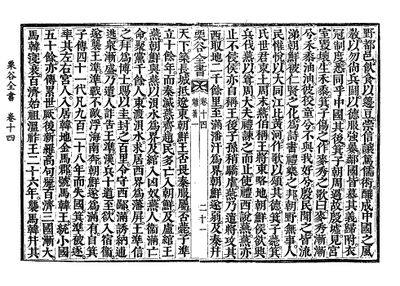

其田野都邑。飮食以籩豆。崇信讓篤儒術。釀成中國之風敎。以勿尙兵鬪。以德服强暴。鄰國皆慕其義歸附。衣冠制度。悉同乎中國。其後。箕子朝周。過故殷墟。見宮室毀壞。生朱黍。箕子傷之。作麥秀之歌曰。麥秀漸漸兮。禾黍油油。彼狡童兮。不與我好兮。殷民聞之。皆流涕。朝鮮被仁賢之化。爲詩書禮樂之邦。朝野無事。人民懽悅。以大同江比黃河。作歌以頌其德。箕子薨。箕氏世君東土。周末。燕伯稱王。將東略地。朝鮮侯欲興兵伐燕以尊周。大夫禮諫之而止。使禮西說燕。燕亦止不侵。侯亦自稱王。後子孫稍驕虐。燕乃遣將攻其西。取地二千餘里。至滿潘汗爲界。朝鮮遂弱。及秦幷天下。築長地抵遼東。朝鮮王否畏秦服。屬。否薨。子準立十餘年。而秦滅燕,齊,趙。民多亡入朝鮮。及盧綰王燕。朝鮮與燕以浿水爲界。及綰入凶奴。燕人衛滿亡命。聚黨千餘人。東渡浿水。求居西界爲藩屏。王準信之。拜爲博士。賜以圭。封之百里。令守西鄙。滿誘納逋逃。衆漸盛。乃遣人詐告王準。漢兵十道至。欲入宿衛。遂襲王準。戰不敵。浮海南奔。朝鮮遂爲滿有。自箕子傳四十一代凡九百二十八年而失國。箕準被逐。率其左右宮人。入居韓地金馬郡。號馬韓王。統小國五十餘。亦傳累世。厥後新羅,高句麗,百濟三國漸大。馬韓寖衰。百濟始祖溫祚王二十六年。襲馬韓幷其國。 |

(translation) |

|

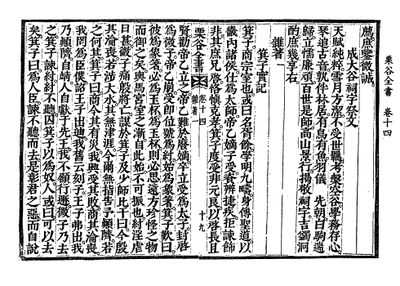

箕氏主馬韓又二百年而亡。傳祚前後凡一千一百二十餘年。 贊曰。猗歟大師。運遭明夷。內貞而晦。制義隨時。被髮操音。惟天我知。宗國旣淪。嗚呼曷歸。法授蒼姬。身莅靑㙨。誕闢土宇。樂浪作京。鰈域長夜。肇照日星。禁設八條。文宣禮樂。江淸大同。山重太白。子孫繩繩。千祀是卜。五世不斬。迄受遺澤。報祀仁辟。極天如昨。 謹按。天生蒸民。必降聖賢以主之。輔相化育。宣朗人文。以遂其生。以立其敎。伏羲以下。迄于三王。代天開物。故命之以我東有民。想不後中國。未聞睿智有作。以盡君師之責。檀君首出。文獻罔稽。恭惟箕子。誕莅朝鮮。不鄙夷其民。養之厚而敎之勤。變魋結之俗。成齊魯之邦。民到于今。受其賜。禮變之習。濟濟不替。至於夫子。有浮海欲居之志。則微禹之嘆。沒世愈深矣。大哉箕子。旣陳洪範於武王。道明于華夏。推其緖餘。化洽于三韓。子孫傳祚千有餘年。後辟景仰。若揭日月。崇德報功。世篤其典。苟非元聖。烏能致此。嗚呼盛矣哉。齊人只知有管,晏。此固不免坐井。至於洙泗之儒。深繹夫子微言。洛閩之士。偏傳程朱遺敎。亦其理宜也。我東受箕子罔極之恩。其於實迹。宜家誦而人熟也。然今之土。被人猝問。鮮能條答。蓋由羣書散漫。學之不博也。 |

(translation) |

|

尹公斗壽曾奉使朝 天。中朝士人。多問箕子之爲。尹公病不能專對。旣還。乃廣考經史子書。裒集事實及聖賢之論。下至騷人之詠。摭而成書。名曰。箕子志。其功良勤。而其嘉惠後學。亦云至矣。第念雜編徑傳。統紀難尋。珥乃不揆僭濫。竊採志中所錄。約成一篇。因略敍立國始終。世系歷年之數。名曰箕子實紀。庶便觀覽焉。 萬曆八年庚辰仲夏。後學德水李珥。謹志。 |

(translation) |

- Discussion Questions:

References

한영우. 1982. 고려-조선전기의 기자인식. 한국문화. 제 3권. 김영민. 2012. 조선시대 시민사회론의 재검토. 한국정치연구 제21집 제3호. Wang Sixiang. 2015. Co-constructing Empire in Early Chosŏn Korea: Knowledge Production and the Culture of Diplomacy, 1392–1592. Ph.D Dissertation, Columbia University.

Footnotes

- ↑ 한영우. 1982. 고려-조선전기의 기자인식. 한국문화. 제 3권.

- ↑ For the significance of term 君師 for Neo-Confucian political thought, see 김영민. 2012. 조선시대 시민사회론의 재검토. 한국정치연구 제21집 제3호, 13쪽.

- ↑ 大哉箕子。旣陳洪範於武王。道明于華夏。推其緖餘。化洽于三韓。This parallel of the Great Plan and Kija's teaching in Korea appears first in Chŏng Dojŏn's 朝鮮經國典 國號. "箕子陳武王以洪範。推衍其義。作八條之敎." http://db.itkc.or.kr/inLink?DCI=ITKC_MO_0024A_0100_010_0020_2003_A005_XML

- ↑ The italicized text is the translation of the Great Plan of the Book of Zhou(周書 洪範)by James Legge. This part is a verbatim citation of this part of the Book of Zhou. https://ctext.org/shang-shu/great-plan?searchu=%E7%AE%95%E5%AD%90&searchmode=showall#result