"Certificate of Manumission for the House Slave"의 두 판 사이의 차이

(새 문서: {{Primary Source Document |Image = 약가노인발문.JPG |English = Certificate of Manumission for the House Slave |Chinese = 約家奴善一契券, 約家奴仁發文 |Korean = 약...) |

(차이 없음)

|

2017년 2월 15일 (수) 14:19 판

| Primary Document | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | |

| English | Certificate of Manumission for the House Slave |

| Chinese | 約家奴善一契券, 約家奴仁發文 |

| Korean | 약가노선일계권, 약가노인발문 |

| Document Details | |

| Genre | Social Life and Economic Strategies |

| Type | Record |

| Author(s) | Yi Hyeongsang (李衡祥, 1653-1733) |

| Year | |

| Key Concepts | |

| Translation Info | |

| Translator(s) | Participant of 2016 Jangseogak Hanmun Workshop Program |

| Editor(s) | Song Jaeyoon, Hyeok Hweon Kang |

| Year | 2016 |

Primary Source Text

| English | Classical Chinese |

|---|---|

|

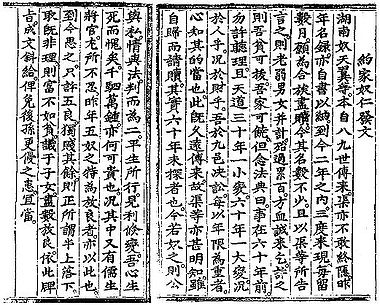

Certificate of Manumission for the House Slave Sŏnil

|

約家奴善一契券

|

|

Certificate of Manumission for the House Slaves Inbal et al.

|

約家奴仁發文

|

Discussion Questions

- Was Korea a slave society? What constitutes a slave or a slave society? Is nobi a slave?

- Why is slavery not discussed in Korean historiography as much?

- How does the idea of a land-owning slave or an outside-resident slave different from the slaves we are familiar with?

- How might you compare the nobi system with slavery institutions from elsewhere in the world? Is the nobi system qualitatively different from, for example, American slavery? Is it appropriate or useful to compare the two? Is it problematic to use universalizing analytic categories such as slavery to frame research?

- What does this document tell us about the position and mobility of slaves in Choson society? Who is determining for us how to understand this case? To what extent does this document appear as formulaic rhetoric? Can we ever know a slave’s opinion?

- Why would a male slave want his family to be reincorporated into his master’s family after 60 years of “freedom” (fending for themselves without paying tribute to the master)? What is the main driving force behind Yi Hyŏngsang’s manumission of slaves? How do the two cases differ in this regard? What is his attitude towards wealth, as suggested in the second document?

Further Readings

- Ellen Salem. “The Landowning Slave.” Korea Journal 16:4 (April 1976): 27-34.

- Ellen Salem. “Slavery in Medieval Korea.” Unpubl. Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, (1978).

- Ellen Salem. “The Utilization of Slave Labor in the Koryŏ Period; 918-1392.” Papers of the 1st International Conference on Korean Studies, 1980: 630-642.

- Kim Hyong-in, “Rural Slavery in Antebellum South Carolina and Early Chosŏn Korea,” Ph.D dissertation, University of New Mexico, 1990.

- Palais, James B. “Slavery and Slave Society in the Koryŏ Period,” Journal of Korean Studies 5 (1984): 173-90.

- Rhee Young-hoon and Yang Donghyu. “Korean Nobi in American Mirror: Yi Dynasty Coerced Labor in Comparison to the Slavery in the Antebellum Southern United States.”

- Kim, Chong Sun. “Slavery in Silla and its Sociological and Economic Implications.” in Andrew G. Nahm, ed., Traditional Korea: Theory and Practice (1974): 29–43.

- Kim Kichung. “Unheard Voices: The Life of the Nobi in O Hwi-mun’s Swaemirok.” Korean Studies 27 (2003): 10–37.

- “Case 3. Yi Pong-dol: A Defiant Slave Challenges His Overlord with Death (Anŭi, Kyŏngsang Province, 1842).” In Sun Joo Kim and Jungwon Kim, Wrongful Deaths: Selected Inquest Records from Nineteenth-Century Korea. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014), 55–61.

- Kim, Joy Sung-hee, “Representing Slavery. Class and Status in Late Chosŏn-Korea,” Ph.D dissertation, Columbia University, 2004.