"(Translation) 1801年 李希誠 衿給文記"의 두 판 사이의 차이

Sanghoon Na (토론 | 기여) 잔글 |

Sanghoon Na (토론 | 기여) |

||

| 19번째 줄: | 19번째 줄: | ||

=='''Introduction'''== | =='''Introduction'''== | ||

| − | There are three types of property distribution record (''punjaegi'' 分財記): the record of bequeathal (''hŏyŏmun’gi'' 許與文記) for inheritance to posterity, the record of amiable agreement (''hwahoemun’gi'' 和會文記) for the property distribution among siblings regarding intestate succession, and the record of special bequeathal (''pyŏlgŭpmun’gi'' 別給文記) for inheritance to those who had special merits. | + | There are three types of property distribution record (''punjaegi'' 分財記): the record of bequeathal (''hŏyŏmun’gi'' 許與文記) for inheritance to posterity, the record of amiable agreement (''hwahoemun’gi'' 和會文記) for the property distribution among siblings regarding intestate succession, and the record of special bequeathal (''pyŏlgŭpmun’gi'' 別給文記) for inheritance to those who had special merits, such as success in the civil service examination. |

| − | This record belongs to the first category | + | This record belongs to the first category, the record of bequeathal. It has a distinctive feature that deals with a cooperative association called ''kye'' (lit. “contract” or “bond”) organized for the purpose of mutual aid in the event of financial needs.<ref> For more information about the Korean ''kye'', see Gerard F. Kennedy, “The Korean Kye: Maintaining Human Scale in a Modernizing Society,” Korean Studies 1 (1977): 198 </ref> It is noteworthy that this association member consisted of a master and his slaves and thus was named slave-master association (''noju kye'' 奴主契). |

| − | Yi Huisŏng (李希誠, fl. 1741) and his ten slaves raised a grain fund by paying half and half and formed the slave-master association both for himself and for the slaves. For example, the grain was used for him to pay for the restoration of his fences. It was also used for the slaves to avoid corvée labor. In other words, when the labor imposed upon them, they could buy others to work for them by means of the grain fund of the association. It is significant that this association was organized in 1741 when many slaves fled from their masters. By allowing them to do so, the owner was able to retain his slaves under the pretext of protecting them. | + | According to this document, Yi Huisŏng (李希誠, fl. 1741) and his ten slaves raised a grain fund by paying half and half and formed the slave-master association both for himself and for the slaves. For example, the grain was used for him to pay for the restoration of his fences. It was also used for the slaves to avoid corvée labor. In other words, when the labor imposed upon them, they could buy others to work for them by means of the grain fund of the association. It is significant that this association was organized in 1741 when many slaves fled from their masters. By allowing them to do so, the owner was able to retain his slaves under the pretext of protecting them. |

In the end, however, Yi Huisŏng broke up the association and gave the grain to his son, Yi Rip 李岦 in 1801. It is also significant that 66,067 public slaves were emancipated at that time. He states in this record that he could not maintain the association because some slaves spent the grain and ran away or died, and other slaves left him for another family by marrying to a commoner or to another master’s slave. | In the end, however, Yi Huisŏng broke up the association and gave the grain to his son, Yi Rip 李岦 in 1801. It is also significant that 66,067 public slaves were emancipated at that time. He states in this record that he could not maintain the association because some slaves spent the grain and ran away or died, and other slaves left him for another family by marrying to a commoner or to another master’s slave. | ||

2018년 7월 18일 (수) 18:31 판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | ||

| Chinese | 1801年 李希誠 衿給文記 | |

| Korean(RR) | 1801년 이희성 깃급문기 (Yi Hui-seong gis-geub-mun-gi) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Social Life and Economic Strategies | |

| Type | Record | |

| Author(s) | 李希誠 | |

| Year | 1801 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | Master-slave Compact | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | ||

| Year | 2018 | |

목차

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Original Script

- 3 Discussion Questions

- 4 Further Readings

- 5 References

- 6 Translation

- 6.1 (sample) : Jaeyoon Song

- 6.2 Student 1 : (Write your name)

- 6.3 Student 2 : (Write your name)

- 6.4 Student 3 : Hu JIng

- 6.5 Student 4 : Martin

- 6.6 Student 5 : Inho Choi

- 6.7 Student 6 : Kanghun Ahn

- 6.8 Student 7 : King Kwong Wong

- 6.9 Student 8 : Younès M'Ghari

- 6.10 Student 9 : (Mengheng Lee)

- 6.11 Student 10 : (Ji-Hyun Lee)

- 6.12 Student 11 : Lee Goeun

- 6.13 Student 12 : Sanghoon Na

- 6.14 Student 13 : (Write your name)

- 6.15 Student 14 : (Write your name)

Introduction

There are three types of property distribution record (punjaegi 分財記): the record of bequeathal (hŏyŏmun’gi 許與文記) for inheritance to posterity, the record of amiable agreement (hwahoemun’gi 和會文記) for the property distribution among siblings regarding intestate succession, and the record of special bequeathal (pyŏlgŭpmun’gi 別給文記) for inheritance to those who had special merits, such as success in the civil service examination.

This record belongs to the first category, the record of bequeathal. It has a distinctive feature that deals with a cooperative association called kye (lit. “contract” or “bond”) organized for the purpose of mutual aid in the event of financial needs.[1] It is noteworthy that this association member consisted of a master and his slaves and thus was named slave-master association (noju kye 奴主契).

According to this document, Yi Huisŏng (李希誠, fl. 1741) and his ten slaves raised a grain fund by paying half and half and formed the slave-master association both for himself and for the slaves. For example, the grain was used for him to pay for the restoration of his fences. It was also used for the slaves to avoid corvée labor. In other words, when the labor imposed upon them, they could buy others to work for them by means of the grain fund of the association. It is significant that this association was organized in 1741 when many slaves fled from their masters. By allowing them to do so, the owner was able to retain his slaves under the pretext of protecting them.

In the end, however, Yi Huisŏng broke up the association and gave the grain to his son, Yi Rip 李岦 in 1801. It is also significant that 66,067 public slaves were emancipated at that time. He states in this record that he could not maintain the association because some slaves spent the grain and ran away or died, and other slaves left him for another family by marrying to a commoner or to another master’s slave.

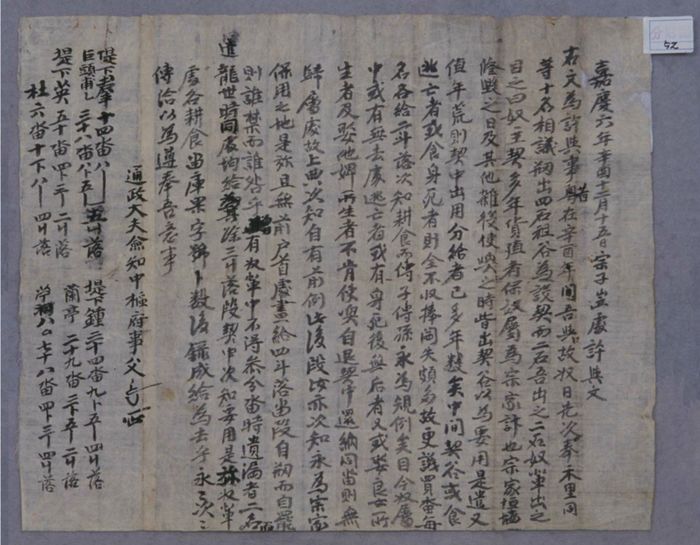

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

嘉慶六年辛酉十二月十五日宗子岦處許與文 右文爲許與事 昔在辛酉年間 吾與故奴日先次奉禾里同等十名相議 刱出四石租谷爲設契 而二石吾出之 二石奴輩出之 因之曰奴主契 多年貨殖者 保奴屬爲宗家計也 宗家坦檣修毁之日 及其他雜役使喚之時 皆出契谷 以爲要用是遣 又値年荒 則契中出用分給者 已多年數矣 中間契穀[2] 或食或逃亡者 或食身死者 則全不收捧 閪失頗多 故更議買畓 每名各給二斗落[3]次知耕食 而傳子傳孫 永爲規例矣 目今奴屬中 或有無去處逃亡者 或有身死後無後者 又或娶良女所生者 及娶他婢所生者 不肯使喚 自退契中 還納同畓 則無歸屬處 故上典次知自有前例 此後段 汝亦次知 永爲宗家保用之地是旀 且無前戶首處劃給四斗落段 自刱而自罷 則誰禁而誰咎乎 曾有奴輩中 不得參分畓時遺漏者二名 而龍世時同處均給爲㫆 其餘三斗落段 契中次知要用是旀 奴輩處各耕食畓庫果 字號卜數後錄成給爲去乎 永永次次 傳給以爲遵奉吾意事 通政大夫僉知中樞府事 父 (着名署押)

(後錄 -생략)

|

(translation) 李希誠 奴主契 許與文 (1801) 嘉慶六年辛酉十二月十五日宗子岦處許與文 The document of property distribution to the legitimate son, Rip, on the fifth day of the twelfth month of the year sinyu [1801], the sixth year of the Jiaqing Emperor's reign (1796-1820).

The document mentioned on the right is to bequeath my property as follows:

Earlier, in the year sinyu [1741], I and ten slaves, including the late slaves Ilseon, Cha'bong, and Hwaridong, had a discussion to set aside four sŏk of rice and formed an association (kye 契).

I offered two sŏk and a group of slaves presented the other two sŏk, thereby calling it slave-master association (noju kye 奴主契).

For many years we increased profits to protect slaves and to do good head family.

[For example,] when the family had to renovate the fences and slaves were employed to do miscellaneous menial tasks, all of us could take grain out of the compact granary for the necessary purposes.

Also encountering a drought, we have taken grain from the compact and distributed evenly amongst us.

Meanwhile, some ate grain and ran away, and others ate and then died, so we could not recollect them and such losses were huge.

Therefore, we discussed again and bought rice paddies. I distributed two turak of the paddies to each to live on them, and I made it a lasting ordinance to pass them down to descendants.

Now, there are slaves as follows: who ran away without any permanent place; who died without leaving any descendants; who married to a commoner woman and their children became commoners; who took another master’s slave as a wife and their children belonged to the master.

All of them would not work for this family, backed out of the compact, and returned the paddies. But since there was no place to return, the owner was supposed to take charge of them according to a precedent.

From now on, you [my son] will be in charge of them and make them a permanent property of this main house.

In addition, as for the four turak given to heads of households who were not present before, they were voluntarily pooled and given up, so who could be forbidden and who could be blamed?

Earlier there were two slaves who did not take part in the paddy distribution and were left out. They are Yongse and Sidong to whom you ought to distribute the land evenly.

As for the rest, three turak, they shall belong to the compact land and be used for its need.

As for the paddies distributed to slaves, I will state their location and yields in the postscript.

You shall respect my will by transmitting them for generation after generation, forever.

Great Master of Thoroughly Administrative (Tongjeong taebu) and Fifth Minister at the Office of Ministers-without-Portfolio, Father 【Put your name and signature】

The postscript is omitted.

|

Discussion Questions

Further Readings

References

- ↑ For more information about the Korean kye, see Gerard F. Kennedy, “The Korean Kye: Maintaining Human Scale in a Modernizing Society,” Korean Studies 1 (1977): 198

- ↑ ‘契谷’은 契員이 出資한 곡식으로서 ‘契穀’이 맞으나 음가가 같으므로 ‘谷’자로도 흔히 사용하였다.

- ↑ 畓二斗落=600坪(1斗落=300坪, 1坪 =3.3058㎡)=1,983.48㎡=0.49ac(1ac=4,047㎡)

Translation

(sample) : Jaeyoon Song

- Discussion Questions:

Student 1 : (Write your name)

old document, slavery-slave compact, economic and social status of slaves , property distribution

- Discussion Questions:

Is all these documents written by the owner of the slaves themselves or by someone at a specific position? How are they going to ensure the legality of these compact?

Student 2 : (Write your name)

key words: slaves, master, compact, land, property, descendants social history, social mobility, tenant farmers,

- Discussion Questions:

What were the significances of the abolishment of 從賤法 and establishment of 從良法?

Student 3 : Hu JIng

- key words: yangban-nobi relation, economic life in Joseon, compact, social mobility in Joseon

- Discussion Questions:

1. What can we learn from this document with regard to the relation between the yangban and nobi in Joseon dynasty, particularly when thinking of that the slavery system was under transition at the point?

Student 4 : Martin

Inheritance Practices, Transformation of Korean slavery system

- Discussion Questions:

1. What does the document tell about the economical costs and value of slavery?

2. Following the contents of the document describing the inheritance of the compact between slaves and master, who actually benefited from the establishment of the contract?

Student 5 : Inho Choi

Master-Slave compact, Inheritance, Choson Slavery, Choson social history, Social Mobility

- Discussion Questions:

Is 契 a financial arrangement, a legal document, or both. Is 契 a exclusively private arrangement, or does government somehow guarantee its effect and helps its enforcement? Is there any shift in the meaning of 奴 in the early 19th century that allows them to make a compact with their master?

Student 6 : Kanghun Ahn

Choson social history, inheritance, property distribution, Korean slavery,

- Discussion Questions: How many 奴主契 documents can be found from the Choson dynasty? Was it kind of a common practice? And what sort of sociopolitical significance (or implication) does it have on Choson social history as a whole?

Student 7 : King Kwong Wong

- Keywords:

economic and social relationship between master and slaves, changing social condition, hereditary status of slaves

- Discussion Questions:

- How does this document reveal the relationship between master and slaves?

- How does this document tell about the status of slaves during the Joseon period?

- For what purposes, do both parties have this kind of agreement?

- What does this document tell us about the social condition of the time?

Student 8 : Younès M'Ghari

- Key Concepts:

Chosôn, social history, legacy transmission, contract between slaves and the master

- Discussion Questions:

Could the clauses of this contract be in conflict with the ones of the former slave contracts (there is no mention of "this contract hereby cancels the previous contract")? How would the author of this contract avoid such issues?

How would the slaves understand the contract if it is written in Korean Literary Sinitic language?

Student 9 : (Mengheng Lee)

- keyword:

slavery, the social status system, and social mobility in Chosŏn Korea, slave-master compact, and documents of distribution of property.

- Discussion Questions:

1. To what extent could we say that this document shows the upward social mobility in Chosŏn Korea?

2. What is the nature of slave-master compact that we can conceptualize from this document?

3. What's the historical significance of this document?

Student 10 : (Ji-Hyun Lee)

奴主契 slave-master compact,

奴婢 slavery

宗家 head-family

分財記 inheritance document

land and property distribution

Chosŏn contract

- Discussion Questions:

1. How would the inheritance of the 2 durak be changed in case of the demographic changes among the slaves, ex. more children in one slave's house whereas no children in the other's?

2. From where did the slaves employ the substitute laborers to fix the walls and to be paid?

3. How are the slaves in Korea different from serfs or peasants in European feudalism?

Student 11 : Lee Goeun

- Discussion Questions: Since when such compact between master and slaves began to appear in Joseon? Was this common in the society? Was there a regional difference or tendency?

- Key Concepts: Changing social strata in the turn to 19c Joseon

Student 12 : Sanghoon Na

- Discussion Questions:

How does Yi Huiseong rationalize/justify his distributing property to only his son?

How does the matrilineal rule for slaves (奴婢從母法) in the seventh year of King Yeongjo's reign(1731) affect this document issued in 1801?

- Key Concepts: Slave-master compact, mutual discussion 相議

Student 13 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 14 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions: