"(Translation) 朴突夢傳"의 두 판 사이의 차이

(→Student 10 : (YoungSuk)) |

잔글 |

||

| (사용자 4명의 중간 판 14개는 보이지 않습니다) | |||

| 23번째 줄: | 23번째 줄: | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | A folk tale of Pak Tolmong was part of the collection of tales 『里鄕見聞錄』 "Ihyang gyeonmunrok" (Records of Memories from the Lanes and Villages) compiled by Yu Jaegeon 劉在建 (1793-1880) in 1862 (late Joseon). The compilation was somewhat unusual. It included narratives about representatives of lower and middle classes of the society or so-called 委巷人 ''wihangin'' (alley people), such as low-level officials and clerks and village residents. The collection also included narratives about Buddhist monks and slaves, as in the case of the story in question. Therefore, this tale can be valued not only as a piece of literature but also as a rich source of information on social realities of late Joseon at the time, such as the dynamics between the classes and notions of social mobility. We can also catch a glimpse of strong prevalence of Neo-Confucian values and its philosophy.<br /> | ||

| + | Author of the compilation worked in Kyujanggak 奎章閣 , a royal library established by King Jeongjo 正祖 in 1776. He was a low-level official himself, so it might suggest that his own status was part of his motivation to compile such narratives circulating at that time.<br /> | ||

| + | Tales in the collection, such as "Pak Tolmong," shared a similar narrative pattern. Protagonists of the stories, lower members of the society, express extreme diligence in learning, educate themselves in Confucian Classics, and impress others by their high level of literacy and knowledge of ethical standards propagated by Neo-Confucianism. The tale in question and the rest of the tales included in the collection expressed a prominent notion at the time: desire of ''wihangin'' members to elevate their status which put them up against the ''yangban'', privileged aristocrats, part of a rather ossified and immobile social structure. <br /> | ||

| + | At the same time, the tales are not idealized and rather realistic, in a sense that in the end the protagonists, while working hard to realize their dream, do not achieve a high position. We can also say that overall the tales are rather cautious and do not express openly the idea of striving to become part of ''yangban''. There were no radical ideas of subversion of authority and toppling of ''yangban''. Characters abide by Neo-Confucian values and moral principles. The lower status subject in question would defer to the higher ranks; Tolmong would loyally obey his master and would not sever ties with him. Therefore, the private yearning of raising one's status is deemphasized and would never interfere with the sacred hierarchical relationships, such as king-subject, father-son, or accordingly, master-servant.<br /> | ||

| + | The story suggests that while the common people based on their ability could be on the same level with ''yangban'' (or even higher, if we take the example of Tolmong and his master's son) in terms of literacy and education, the equality in social status, based on ethical standards deeply engraved in the society at the time, was still not possible. | ||

=='''Original Script'''== | =='''Original Script'''== | ||

{|class="wikitable" style="width:100%; font-size:110%; color:#002080; background-color:#ffffff;" | {|class="wikitable" style="width:100%; font-size:110%; color:#002080; background-color:#ffffff;" | ||

| − | !style="width: | + | !style="width:23%;"|Classical Chinese || style="width:77%;"| English |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| 57번째 줄: | 62번째 줄: | ||

|| | || | ||

| − | ( | + | Pak Tol-mong was a slave, paying tribute to the Kim family. Ever since he could speak he was aiming to learn reading and writing. However, his status did not allow him to have a teacher. Kim's family had a son. Every time the boy sat in the study room to read texts, Tol-mong followed him and watched the lesson from aside. Though Tol-mong could not understand the meaning, he followed the reading and remembered the words. Kim's son often forgot the pronunciation of a word and asked Tol-mong. |

| + | |||

| + | In the neighborhood there lived one Mr. Jeong, he stayed at home and gave lessons. As soon as Tol-mong tied up his hair (got married), he went to Mr. Jeong and asked to take classes. The teacher allowed him to do so. Tol-mong woke up at daybreak, embracing books he waited at the gate of the teacher's place. After the gates were opened he dare to enter. Lowering his head he swiftly approached the door of the teacher's bed chamber, and deferentially waited for the teacher to rise up. The teacher, knowing that he has arrived, asked through the window, "Tol-mong, are you here?" Tol-mong responded, "Yes." | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the group of disciples arrived later they all together entered the classroom. Tol-mong was ashamed of himself wearing a slave hat as he was lining up with students wearing scholarly gowns and ivory bodkins. He could not dare to enter the classroom moving his legs reluctantly. The teacher used his discretion to cover [Tolmong's identity as a slave] with a turban and made him enter. After taking a class he returned home and provided service as before. Nobody in Kim’s family knew about that. At the end of the year, he learned the Elementary Learning, the Analects and the Mencius. His knowledge of letters improved every day, and the teacher thought he was quite extraordinary. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His duty was to chop and tie up fire woods. Whenever he was axing and tying up the woods, he never failed to recite from the classics. People in the house pointed him as a moron. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [Because the master] was always afraid of catching malaria, the Kims gave him a break to cure his disease. Tol-mong privately told his wife saying, "This is the time of my studying." He went to his room, put on his hat, and tie up the string. He sat solemnly and read books aloud. The symptoms of malaria began to show, which made him shiver inside and had his teeth tremble. However, he sat more solemnly. His mouth never stopped reciting [books]. Three days later, his disease has already been cured. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Later his wife washed her clothes at the Tangcheon creek. On the flat stone, Tol-mong took off his hat, put up his pants, and sit down there. Then, he rubbed an ink stick on an ink stone, held his brush, and started to write the preface to the Elementary Learning, so it spread over the surface of the stone. In the evening, he moved, and lay down in a shade of a tree, and recited [classics]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The lad of Minister Cho, who was out to enjoy the spring in coincidence, witnessed Tol-mong 's doing and felt quite queer. The lad yelled at him, saying: "Who are you?" Tol-mong stood up gradually, responding, "I am a household servant.". Then the lad said:“Your master is not a human being! How could he allow a household servant to learn the classics and the commentaries? I blame your current master, and would like to be your new master. If you like, I will exempt your slave status." Tol-mong responded: "Because of me, my lord is suffering from blame and criticizing. [So] I cannot leave my old lord out of the righteousness". [By hearing this], the lad esteemed Tol-mong more. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The son of the Kim family grew gradually unrestrained and unbridled. He was not diligent in study. His father scolded him in anger, "You live idly and indulge yourself in being coddled, like a beast looking at meat. You are not even close to Tol-mong [in comparison]." The father chastised him several times, and the son had nowhere to vent his anger. Whenever he saw Tol-mong, he beat him and drove him away. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tol-mong said: “I would rather avoid them,not to cause antagonistic feelings between the father and son of my master’s family. ” He thence used his sickness as a pretext to quit his duty, and moved to live with his wife’s household. The master’s son could not relieve his bitter regret (against Tol-mong), when he met with the master he framed up Tol-mong behind his back. As things turned out, the master grew suspicious against Tol-mong and his wife. Tol-mong lamented: “This is my fate, I dare not to blame it on others!” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Taking his wife, he left home for Namyang prefecture, weaving baskets for a living there. After a year had passed, the sub-district administrator announced the military organization of the prefecture. Tol-mong said: “Weaving baskets is a way of scraping a meager living. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where can I go to earn some more money to pay the military taxes?” Incidentally the provincial examinations for the selection of the local military service men were held. He passed the test with fire arms, however, he did not pass the next level. He became severely depressed and thought about leaving the capital. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He went back to the Kim family. Not long after, he became a clerk in the local prison, and passed away in his forties. For him to become a clerk, Mr. Cho offered his helped. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mr Jeong’s name is Chihu. His character is tame and erudite. He was knowledgeable on geomancy. When he was young, he worked as a minor scribe in the Government Printing Office. <ref>芸館 is another name for 校書館(Government Printing Office) in jeoseon dynasty. </ref> Before getting old, he resigned on the ground of illness, and stayed home to teach students. | ||

| + | |||

|} | |} | ||

=='''Discussion Questions'''== | =='''Discussion Questions'''== | ||

| − | # | + | # What does the story of Tolmong tell us about the social mobility of slaves? Is this a common case or an exceptional one that depends on one's effort and determination? |

| − | # | + | # In the story, a man of status found it inhumane that Tol-mong knows the Classics but still serves as a slave. What does this passage tell us about the nature of this work of literature? What is the story's underlying message about slavery? |

| − | + | # Even though Tolmong is exceptionally diligent and manages to advance beyond his initial status, the final step of advancement seems unattainable even to someone hard working as him. Is this due to his background or does this emphasize the difficulty of the final exams? Can we see this as a critique of the examination system? | |

| + | # Taking into consideration that it was a record of a folk tale what was the purpose of such a story (in both oral and written rendition), to whom was it addressed in each case? | ||

=='''Further Readings'''== | =='''Further Readings'''== | ||

| 71번째 줄: | 102번째 줄: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

--> | --> | ||

| − | * | + | * '''[http://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/ArticleDetail/NODE06609917 『里鄕見聞錄(이향견문록)』 수록 인물의 사회계층적 위상과 신분 관념 The Social Position of the People Included in Ihyanggyeonmunrok and Their View of Status System in the Late Joseon Dynasty]''' |

| − | |||

| − | |||

=='''References'''== | =='''References'''== | ||

| 176번째 줄: | 205번째 줄: | ||

10. 軍租顧安所輸入." 會郡都試鄕兵, 突夢以砲中試, 及會試不果, 因鬱鬱思京洛, | 10. 軍租顧安所輸入." 會郡都試鄕兵, 突夢以砲中試, 及會試不果, 因鬱鬱思京洛, | ||

| − | Where can I go to earn some more | + | Where can I go to earn some more money to pay the military taxes? Incidentally the provincial examinations for the selection of the local military service men were held. He passed the test with fire arms, however, he did not pass the next level. He became severly depressed and thought about leaving the capital. |

| 185번째 줄: | 214번째 줄: | ||

2. What caused his serious depression? | 2. What caused his serious depression? | ||

| − | 3. Tolmong, realizing himself to be the master of life yet a nobi in reality, how did he cope with the discrepancy between the life of idea and that of reality? | + | 3. Tolmong, realizing himself to be the master of life yet a nobi in reality, how did he cope with the discrepancy between the life of idea and that of reality of his own? |

==='''Student 11 : (Lidan Liu)'''=== | ==='''Student 11 : (Lidan Liu)'''=== | ||

2017년 10월 31일 (화) 16:45 기준 최신판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | A folk tale of Pak Tolmong | |

| Chinese | 朴突夢傳 | |

| Korean(RR) | 박돌몽전 | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Old Documents (文書) | |

| Type | ||

| Author(s) | 金洛瑞(Hogojaejip 好古齋集) | |

| Year | - | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | ||

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2017 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | ||

| Year | 2017 | |

목차

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Original Script

- 3 Discussion Questions

- 4 Further Readings

- 5 References

- 6 Translation

- 6.1 Student 1 : (Irina)

- 6.2 Student 2 : (Kim Young)

- 6.3 Student 3 : (Masha)

- 6.4 Student 4 : (Jong Woo Park)

- 6.5 Student 5 : (Kanghun Ahn)

- 6.6 Student 6 : (Hu Jing)

- 6.7 Student 7 : King Kwong Wong

- 6.8 Student 8 : (Zhijun Ren)

- 6.9 Student 9 : 마틴

- 6.10 Student 10 : (YoungSuk)

- 6.11 Student 11 : (Lidan Liu)

- 6.12 Student 12 : (Dohee jeong)

- 6.13 Student 13 : (Write your name)

- 6.14 Student 14 : (Write your name)

- 7 Further Readings

Introduction

A folk tale of Pak Tolmong was part of the collection of tales 『里鄕見聞錄』 "Ihyang gyeonmunrok" (Records of Memories from the Lanes and Villages) compiled by Yu Jaegeon 劉在建 (1793-1880) in 1862 (late Joseon). The compilation was somewhat unusual. It included narratives about representatives of lower and middle classes of the society or so-called 委巷人 wihangin (alley people), such as low-level officials and clerks and village residents. The collection also included narratives about Buddhist monks and slaves, as in the case of the story in question. Therefore, this tale can be valued not only as a piece of literature but also as a rich source of information on social realities of late Joseon at the time, such as the dynamics between the classes and notions of social mobility. We can also catch a glimpse of strong prevalence of Neo-Confucian values and its philosophy.

Author of the compilation worked in Kyujanggak 奎章閣 , a royal library established by King Jeongjo 正祖 in 1776. He was a low-level official himself, so it might suggest that his own status was part of his motivation to compile such narratives circulating at that time.

Tales in the collection, such as "Pak Tolmong," shared a similar narrative pattern. Protagonists of the stories, lower members of the society, express extreme diligence in learning, educate themselves in Confucian Classics, and impress others by their high level of literacy and knowledge of ethical standards propagated by Neo-Confucianism. The tale in question and the rest of the tales included in the collection expressed a prominent notion at the time: desire of wihangin members to elevate their status which put them up against the yangban, privileged aristocrats, part of a rather ossified and immobile social structure.

At the same time, the tales are not idealized and rather realistic, in a sense that in the end the protagonists, while working hard to realize their dream, do not achieve a high position. We can also say that overall the tales are rather cautious and do not express openly the idea of striving to become part of yangban. There were no radical ideas of subversion of authority and toppling of yangban. Characters abide by Neo-Confucian values and moral principles. The lower status subject in question would defer to the higher ranks; Tolmong would loyally obey his master and would not sever ties with him. Therefore, the private yearning of raising one's status is deemphasized and would never interfere with the sacred hierarchical relationships, such as king-subject, father-son, or accordingly, master-servant.

The story suggests that while the common people based on their ability could be on the same level with yangban (or even higher, if we take the example of Tolmong and his master's son) in terms of literacy and education, the equality in social status, based on ethical standards deeply engraved in the society at the time, was still not possible.

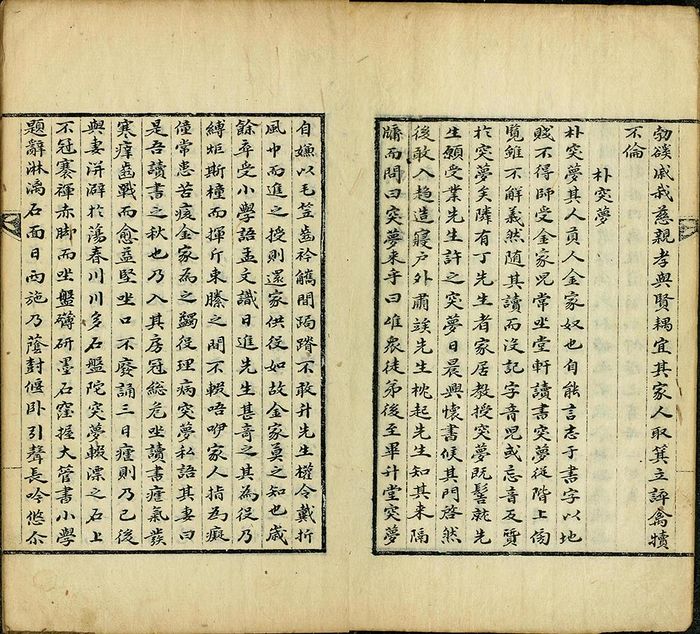

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

1. 朴突夢, 其人貢人, 金家奴也. 自能言, 志于書字, 以地賤不得師受. 金家兒, 常坐堂軒讀書, 突夢從階上傍覽, 雖不解義, 然隨其讀而沒其字音. 兒或忘音, 反質於突夢矣. 2. 隣有丁先生者, 家居敎授, 突夢旣髻, 就先生願受業, 先生許之, 突夢日晨興, 懷書候其門, 啓然後敢入, 趨造寢戶外, 肅竢先生枕起, 先生知其來, 隔牖而問曰, "突夢來乎?" 曰"唯." 3. 衆徒弟後至畢升堂, 突夢自嫌以毛笠齒衿, 觿間跼蹐不敢升, 先生權令戴折風巾而進之, 授則還家, 供役如故, 金家莫之知也. 歲餘卒受小學語孟, 文識日進, 先生甚奇之. 4. 其爲役乃縛炬斯橦, 而揮斤束縢之間, 不輟唔咿, 家人指爲癡僮. 常患苦痎, 金家爲之蠲役理病, 突夢私語其妻曰, 是吾讀書之秋也. 乃入其房冠總, 危坐讀書, 瘧氣發寒㾕齒戰, 而愈益堅坐, 口不廢誦, 三日瘧則乃已. 5. 後與妻洴澼於蕩春川, 川多石盤陀, 突夢輟漂之石上, 不冠褰褌, 赤脚而坐, 盤礴硏墨石窪, 握大管書小學題辭, 淋漓石面, 日西施, 乃蔭樹偃臥, 引聲長吟, 悠尒自得. 6. 趙尙書家郞, 適遊春蕩春 見其所爲, 心異之, 就而呼曰, "爾何爲者?" 突夢徐起而對曰, "家人奴也." 郞曰 "而主非人也, 豈有學經傳而爲人奴者乎? 吾爲爾責而主, 而免而身." 曰, "以奴故, 令老主覯閔, 義不敢出也." 郞尤重之. 7. 金家兒長益挑達, 不勤學, 其父恚罵曰, "汝逸居肆姐, 禽鹿視肉, 反不若突夢." 數督過之, 兒無所起怒, 見突夢, 輒抶驅之. 8. 突夢曰 "吾寧避之, 以定主家父子間, 乃辭以病不任役, 移居其妻之家 兒憾毒不釋, 見主家陰以他事搆害之, 主家果疑其夫妻, 突夢乃歎曰 "命也, 敢誰怨乎!" 9. 挈其妻 流寓南陽郡, 織籠爲生, 歲餘, 里正白郡編之束伍, 突夢曰, "織籠所以餬口也. 10. 軍租顧安所輸入." 會郡都試鄕兵, 突夢以砲中試, 及會試不果, 因鬱鬱思京洛, 11. 還歸金家, 居無何爲典獄吏, 年四十餘卒, 其作吏, 趙郞有力焉. 12. 丁先生致厚其名, 爲人淳素篤學, 兼善風水說, 少爲芸館小史, 未老以病謝歸, 閉門敎授. |

Pak Tol-mong was a slave, paying tribute to the Kim family. Ever since he could speak he was aiming to learn reading and writing. However, his status did not allow him to have a teacher. Kim's family had a son. Every time the boy sat in the study room to read texts, Tol-mong followed him and watched the lesson from aside. Though Tol-mong could not understand the meaning, he followed the reading and remembered the words. Kim's son often forgot the pronunciation of a word and asked Tol-mong. In the neighborhood there lived one Mr. Jeong, he stayed at home and gave lessons. As soon as Tol-mong tied up his hair (got married), he went to Mr. Jeong and asked to take classes. The teacher allowed him to do so. Tol-mong woke up at daybreak, embracing books he waited at the gate of the teacher's place. After the gates were opened he dare to enter. Lowering his head he swiftly approached the door of the teacher's bed chamber, and deferentially waited for the teacher to rise up. The teacher, knowing that he has arrived, asked through the window, "Tol-mong, are you here?" Tol-mong responded, "Yes." After the group of disciples arrived later they all together entered the classroom. Tol-mong was ashamed of himself wearing a slave hat as he was lining up with students wearing scholarly gowns and ivory bodkins. He could not dare to enter the classroom moving his legs reluctantly. The teacher used his discretion to cover [Tolmong's identity as a slave] with a turban and made him enter. After taking a class he returned home and provided service as before. Nobody in Kim’s family knew about that. At the end of the year, he learned the Elementary Learning, the Analects and the Mencius. His knowledge of letters improved every day, and the teacher thought he was quite extraordinary. His duty was to chop and tie up fire woods. Whenever he was axing and tying up the woods, he never failed to recite from the classics. People in the house pointed him as a moron. [Because the master] was always afraid of catching malaria, the Kims gave him a break to cure his disease. Tol-mong privately told his wife saying, "This is the time of my studying." He went to his room, put on his hat, and tie up the string. He sat solemnly and read books aloud. The symptoms of malaria began to show, which made him shiver inside and had his teeth tremble. However, he sat more solemnly. His mouth never stopped reciting [books]. Three days later, his disease has already been cured. Later his wife washed her clothes at the Tangcheon creek. On the flat stone, Tol-mong took off his hat, put up his pants, and sit down there. Then, he rubbed an ink stick on an ink stone, held his brush, and started to write the preface to the Elementary Learning, so it spread over the surface of the stone. In the evening, he moved, and lay down in a shade of a tree, and recited [classics]. The lad of Minister Cho, who was out to enjoy the spring in coincidence, witnessed Tol-mong 's doing and felt quite queer. The lad yelled at him, saying: "Who are you?" Tol-mong stood up gradually, responding, "I am a household servant.". Then the lad said:“Your master is not a human being! How could he allow a household servant to learn the classics and the commentaries? I blame your current master, and would like to be your new master. If you like, I will exempt your slave status." Tol-mong responded: "Because of me, my lord is suffering from blame and criticizing. [So] I cannot leave my old lord out of the righteousness". [By hearing this], the lad esteemed Tol-mong more. The son of the Kim family grew gradually unrestrained and unbridled. He was not diligent in study. His father scolded him in anger, "You live idly and indulge yourself in being coddled, like a beast looking at meat. You are not even close to Tol-mong [in comparison]." The father chastised him several times, and the son had nowhere to vent his anger. Whenever he saw Tol-mong, he beat him and drove him away. Tol-mong said: “I would rather avoid them,not to cause antagonistic feelings between the father and son of my master’s family. ” He thence used his sickness as a pretext to quit his duty, and moved to live with his wife’s household. The master’s son could not relieve his bitter regret (against Tol-mong), when he met with the master he framed up Tol-mong behind his back. As things turned out, the master grew suspicious against Tol-mong and his wife. Tol-mong lamented: “This is my fate, I dare not to blame it on others!” Taking his wife, he left home for Namyang prefecture, weaving baskets for a living there. After a year had passed, the sub-district administrator announced the military organization of the prefecture. Tol-mong said: “Weaving baskets is a way of scraping a meager living. Where can I go to earn some more money to pay the military taxes?” Incidentally the provincial examinations for the selection of the local military service men were held. He passed the test with fire arms, however, he did not pass the next level. He became severely depressed and thought about leaving the capital. He went back to the Kim family. Not long after, he became a clerk in the local prison, and passed away in his forties. For him to become a clerk, Mr. Cho offered his helped. Mr Jeong’s name is Chihu. His character is tame and erudite. He was knowledgeable on geomancy. When he was young, he worked as a minor scribe in the Government Printing Office. [1] Before getting old, he resigned on the ground of illness, and stayed home to teach students. |

Discussion Questions

- What does the story of Tolmong tell us about the social mobility of slaves? Is this a common case or an exceptional one that depends on one's effort and determination?

- In the story, a man of status found it inhumane that Tol-mong knows the Classics but still serves as a slave. What does this passage tell us about the nature of this work of literature? What is the story's underlying message about slavery?

- Even though Tolmong is exceptionally diligent and manages to advance beyond his initial status, the final step of advancement seems unattainable even to someone hard working as him. Is this due to his background or does this emphasize the difficulty of the final exams? Can we see this as a critique of the examination system?

- Taking into consideration that it was a record of a folk tale what was the purpose of such a story (in both oral and written rendition), to whom was it addressed in each case?

Further Readings

References

- ↑ 芸館 is another name for 校書館(Government Printing Office) in jeoseon dynasty.

Translation

Student 1 : (Irina)

朴突夢, 其人貢人, 金家奴也. 自能言, 志于書字, 以地賤不得師受. 金家兒, 常坐堂軒讀書, 突夢從階上傍覽, 雖不解義, 然隨其讀而沒其字音. 兒或忘音, 反質於突夢矣.

Pak Tol-mong was a slave, paying tribute to the Kim family. Ever since he could speak he was aiming to learn reading and writing. However, his status did not allow him to have a teacher. Kim's family had a son. Every time the boy sat in the studying room to read texts, Tol-mon followed him and watched the lesson from aside. Though Tol-mong could not understand the meaning, he followed the reading and remembered the words. It was often Kim's son to forgets the pronunciation of a word and to asks Tol-mong.

- Discussion Questions:

Reading this text we can conclude that the slaves at that time had the freedom to live as they decide. To what extent was slavery in Korea a real deprivation of slaves of human rights, or rather symbolically placing them in a lower position than upper classes?

Student 2 : (Kim Young)

2. 隣有丁先生者, 家居敎授, 突夢旣髻, 就先生願受業, 先生許之, 突夢日晨興, 懷書候其門, 啓然後敢入, 趨造寢戶外, 肅竢先生枕起, 先生知其來, 隔牖而問曰, "突夢來乎?" 曰"唯."

In the neighborhood there lived a Mr. Jeong, he stayed at home and gave lessons. As soon as Dolmong tied up his hair (got married), he went to Mr. Jeong and asked to take classes. The teacher allowed him to do so. Dolmong woke up at daybreak, embracing books he waited at the gate of the teacher's place. After the gates were opened he dare to enter. Lowering his head he swiftly approached the door of the teacher's bed chamber, and deferentially waited for the teacher to rise up. The teacher, knowing that he has arrived, asked through the window, "Dolmong, are you here?" Dolmong responded, "Yes."

- Discussion Questions:

1. The story does not mention Dolmong's child. Based on what we understand about the Joseon slavery system, if Dolmong bore a child, what would have been the life of that child like?

2. In the story, a man of status found it inhumane that Dolmong knows the Classics but still serves as a slave. What does this passage tell us about the nature of this work of literature? What is the story's underlying message about slavery?

Student 3 : (Masha)

3. 衆徒弟後至畢升堂, 突夢自嫌以毛笠齒衿觿間, 跼蹐不敢升, 先生權令戴折風巾而進之, 授則還家, 供役如故, 金家莫之知也. 歲餘卒受小學語孟, 文識日進, 先生甚奇之.

After the group of disciples arrived later they all together entered the classroom. Tolmong was ashamed of himself wearing a slave hat as he was lining up with students wearing scholarly gowns and ivory bodkins. He could not dare to enter the classroom moving his legs reluctantly. The teacher used his discretion to cover [Tolmong's identity as a slave] with a turban and made him enter. After taking a class he returned home and provided service as before. Nobody in Kim family knew about that. At the end of the year, he learned Xiaoxue, Lunyu and Mengzi. His knowledge of letters improved every day, and the teacher thought he was quite extraordinary.

- Discussion Questions:

1. What does it tell us about the role of education and Confucian Classics? The dedication to learning heals Tolmong's disease, yet he does not get a high position. Did the society allow the possibility of the slave to rise up in the society or there were still certain limitations?

2. Taking into consideration that it was a record of a folk tale what was the purpose of such a story (in both oral and written rendition), to whom was it addressed in each case?

Student 4 : (Jong Woo Park)

4. 其爲役乃縛炬斯橦, 而揮斤束縢之間, 不輟唔咿, 家人指爲癡僮.

常患苦痎, 金家爲之蠲役理病, 突夢私語其妻曰, 是吾讀書之秋也. 乃入其房冠總, 危坐讀書, 瘧氣發寒㾕齒戰, 而愈益堅坐, 口不廢誦, 三日瘧則乃已.

His duty was to tie up and chop fire woods. Whenever he was axing and tying up the woods, he never failed to recite from the classics. People in the house pointed him as a moron.

[Because the master] was always afraid of catching malaria, the Kims gave him a break to cure his disease. Tolmong privately told his wife saying, "This is the time of my studying." He went to his room, put on his hat, and tie up the string. He sat solemnly and read books aloud. The symptoms of malaria began to show, which made him shiver inside and had his teeth tremble. However, he sat more solemnly. His mouth never stopped reciting [books]. Three days later, his disease has already been cured.

- Discussion Questions:

Was Tolmong able to escape from his slave status? Doss passing an exam guarantee the elevation of one's status?

Student 5 : (Kanghun Ahn)

後與妻洴澼於蕩春川, 川多石盤陀, 突夢輟漂之石上, 不冠褰褌, 赤脚而坐, 盤礴硏墨石窪, 握大管書小學題辭, 淋漓石面, 日西施, 乃蔭樹偃臥, 引聲長吟, 悠尒自得.

Later his wife washed her clothes at the Tangchun creek. On the flat stone, Tolmong took off his hat, put up his pants, and sit down there. Then, he rubbed an ink stick on an ink stone, held his brush, and started to write the preface to the Elementary Learning, so it spread over the surface of the stone. In the evening, he moved, and lay down in a shade of a tree, and recited [classics].

Discussion questions: Were literate slaves just being disregarded throughout the Choson dynasty? Didn't their masters give any specific roles (functions) toward them?

Student 6 : (Hu Jing)

6. 趙尙書家郞, 適遊春蕩春 見其所爲, 心異之, 就而呼曰, "爾何爲者?" 突夢徐起而對曰, "家人奴也." 郞曰 "而主非人也, 豈有學經傳而爲人奴者乎? 吾爲爾責而主, 而免而身." 曰, "以奴故, 令老主覯閔, 義不敢出也." 郞尤重之.

The lad of Minister Cho, who was out to enjoy the spring in coincidence, witnessed Dolmong's doing and felt quite queer. The lad yelled at him, saying:"Who are you?" Dolmong stood up gradually, responding:"I am a household servant.". The chide said:“Your master is not a human being! How could he allow a household servant to learn the classics and commentaries? I blame your current master, and would like to be your new master. If you like, I will exempt your slave status." Dolmong said:"Because of me, my lord is suffering from blame and criticizing. [So] I cannot leave my old lord out of the righteousness". [By hearing this], the lad esteemed Dolmong more.

- Discussion Questions:

Student 7 : King Kwong Wong

7. 金家兒長益挑達, 不勤學, 其父恚罵曰, "汝逸居肆姐, 禽鹿視肉, 反不若突夢." 數督過之, 兒無所起怒, 見突夢, 輒抶驅之.

The son of the Kim family grew gradually unrestrained and unbridled. He was not diligent in study. His father scolded him in anger, "You live idly and indulge yourself in being coddled, like a beast looking at meat. You are not even close to Tolmong [in comparison]." The father chastised him several times, and the son had nowhere to vent his anger. Whenever he saw Tolmong, he beat him and drove him away.

- Discussion Questions:

- What does the story of Tolmong tell us about the social mobility of slaves? Is this a common case or an exceptional one that depends on one's effort and determination?

Student 8 : (Zhijun Ren)

突夢曰 "吾寧避之, 以定主家父子間, 乃辭以病不任役, 移居其妻之家 兒憾毒不釋, 見主家陰以他事搆害之, 主家果疑其夫妻, 突夢乃歎曰 "命也, 敢誰怨乎!"

Tolmong said: “I would rather avoid them,not to cause antagonistic feelings between the father and son of my master’s family. ” He thence used his sickness as a pretext to quit his duty, and moved to live with his wife’s household. The master’s son could not relieve his bitter regret (against Tolmong), when he met with the master he framed up Tolmong behind his back. As things turned out, the master grew suspicious against Tolmong and his wife. Tolmong lamented: “This is my fate, I dare not to blame it on others!”

Student 9 : 마틴

挈其妻 流寓南陽郡, 織籠爲生, 歲餘, 里正白郡編之束伍, 突夢曰, "織籠所以餬口也

Taking his wife, he left home for Namyang prefecture, weaving baskets for a living there. After a year had passed, the sub-district administrator announced the military organization of the prefecture. Tolmong said: “Weaving baskets is a way of scraping a meager living,

- Discussion Questions:

1. Even though Tolmong is exceptionally diligent and manages to advance beyond his initial status the final step of advancement seems unattainable even to someone hard working as him. Is this due to his background or does this emphasize the difficulty of the final exams? Can we see this as a critique of the examination system?

Student 10 : (YoungSuk)

10. 軍租顧安所輸入." 會郡都試鄕兵, 突夢以砲中試, 及會試不果, 因鬱鬱思京洛,

Where can I go to earn some more money to pay the military taxes? Incidentally the provincial examinations for the selection of the local military service men were held. He passed the test with fire arms, however, he did not pass the next level. He became severly depressed and thought about leaving the capital.

- Discussion Questions:

1. Why did Tolmong fail the exam?

2. What caused his serious depression?

3. Tolmong, realizing himself to be the master of life yet a nobi in reality, how did he cope with the discrepancy between the life of idea and that of reality of his own?

Student 11 : (Lidan Liu)

還歸金家。居無何爲典獄吏,年四十餘卒。其作吏,趙郞有力焉.

He went back to the Kim family. Not long after, he became a clerk in the local prison, and passed away in his forties. For him to become a clerk, Mr. Cho offered his helped.

- Discussion Questions:

Student 12 : (Dohee jeong)

丁先生致厚其名 爲人淳素篤學 兼善風水說 少爲芸館小史 未老以病謝歸 閉門敎授

Teacher jung’s name is chihu. His character is desertion and tame and erudite. Also he was good at geomancy. When he was young, he worked as a minor scribe in Government Printing Office 1). Before getting too old, he resigned on the ground of illness, and stayed home to teach students.

1)芸館 is another name for 校書館(Government Printing Office) in jeoseon dynasty.

- Discussion Questions:

Student 13 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 14 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions: