"(Translation) 除蟲傳敎"의 두 판 사이의 차이

Henrylee2018 (토론 | 기여) (→Introduction) |

|||

| (다른 사용자 한 명의 중간 판 11개는 보이지 않습니다) | |||

| 1번째 줄: | 1번째 줄: | ||

{{Primary Source Document3 | {{Primary Source Document3 | ||

|Image = 제충전교1.jpg | |Image = 제충전교1.jpg | ||

| − | |English = | + | |English = Ordinance on Removing Pests |

|Chinese = 除蟲傳敎 | |Chinese = 除蟲傳敎 | ||

|Korean = 제충전교(''Jechungjeongyo'') | |Korean = 제충전교(''Jechungjeongyo'') | ||

|Genre = [[Royal Documents]] | |Genre = [[Royal Documents]] | ||

| − | |Type = | + | |Type = Decree |

| − | |Author = Jeongjo | + | |Author = King Jeongjo (r. 1776-1800) |

|Year = 1798 | |Year = 1798 | ||

| − | |Key Concepts= | + | |Key Concepts= ordinance, royal tombs, insects, Confucian thoughts and locus, benevolence |

| − | |Translator = | + | |Translator = Ji-Hyun Lee, Sanghoon Na, Goeun Lee, Meng-Heng Lee |

| − | |Editor = | + | |Editor = Ji-Hyun Lee |

|Translation Year = 2018 | |Translation Year = 2018 | ||

| 23번째 줄: | 23번째 줄: | ||

| − | This ordinance by King | + | This ordinance by King Jeongjo is to remove the bugs from the royal tombs. It shows the king's decision of how to deal with those insects that damage the trees planted around the graveyards: hiring people to catch pests and, in turn, driving them into marshland rather than burning them to death. By revealing the ruler’s logic of why he raised the alternative, this text also reflects his being influenced by Neo-Confucianism. |

| − | In 1798, King | + | In 1798, King Jeongjo learned that the trees growing around royal tombs were damaged by insects. After receiving this information, the king initially ordered the authorities to catch the bugs, trying to bring the lasting peace to his deceased ancestors with officials’ physical work, namely, catching the pests and then burning them as precedents in Tang China showed. However, he quickly realized that officials were also his people, of whom he should take care, and whose working force should not be abused. The ruler of the Joseon dynasty then changed his mind. He decided to financially reward the subjects who gathered the harmful creatures. And, instead of burning them, he also commanded administrations to drive those noxious beings into marshland, showing his respect to the righteousness and Heaven’s virtue of sparing lives. His shift between the two plans in this ordinance laid out the Neo-Confucianized mentality of a Joseon king. |

| − | The structure of this ordinance was built on Confucian thoughts and locus. This text began with the king’s highlighting the damage that the bugs cause. To show his reasoning for considering | + | The structure of this ordinance was built on Confucian thoughts and locus. This text began with the king’s highlighting the damage that the bugs cause. To show his reasoning for considering removing the harmful creatures, the ruler referred to several sources, such as the ''Classic of Poetry'', the ''Rites of Zhou'', and the sayings from Zhu Xi. However, the king raised another idea when he thought he should also treat the officials working for him well. To rationalize his reconsideration of the solution, he cited sentences from a poem written by Ouyang Xiu, the ''Compendium of Materia Medica'', ''Taiping Yulan'', and the ''Classic of Poetry''. By utilizing some locus supporting the banishment of the pests to challenge others justifying the execution of burning, at the end of this decree, King Jeongjo adopted the plans of purchasing insects and throwing them to marshlands and commanded his ministers to institutionalize the policies as what had been shown in the previous legal promulgation. |

| + | |||

| + | The importance of this document is: | ||

| + | 1. It manifests the heavy reliance of Joseon court on Confucian ideals and ancient tradition because | ||

| + | 1-1. the king and his subjects are referring to Confucian writings even for matters dealing with insects (經史, 紫陽之訓, 歐陽脩詩) | ||

| + | 1-2. the king was concerned about ethics even for killing insects (生之德並行於其間, 於義有何悖乎). > the king’s care for the dead and the living (both people and insects) | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. This document shows the Confucian transfer of attitude toward the removal of pests 除蟲, which is quite different from the early Joseon dynasty (cf.세종실록 113권, 세종 28년 7월 15일 신사 1번째기사 (1446) http://sillok.history.go.kr/id/kda_12807015_001) | ||

=='''Original Script'''== | =='''Original Script'''== | ||

| 41번째 줄: | 48번째 줄: | ||

|| | || | ||

| − | ( | + | (Translation) |

| + | |||

| + | The [ordinance] message says: | ||

| + | Insects are reducing/damaging fine crops and noble trees [around royal tombs]. How could we not capture and eliminate them? Looking into the classics and history, from the past there had been such positions as that of Mr. Shu and Mr. Jian in “Zhouguan,” all installed for such work. Those feeding on sprouts are myeong (myŏng 螟), those feeding on leaves are teuk (tŭk 螣), those feeding on roots are mo 蟊, and those feeding on joints are jeok (jŏk 賊). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Laying hold of them and throwing them into flames is to pray to the spirit of the Father of Husbandry. Digging down pits to incinerate and bury them has been practiced from Yao Chong (650-721) in the Tang period. The dynasties of the past eventually had laws established based on this, all using people’s labor. As mentioned in Ziyang’s teachings, “How can one stay seated towards the success without getting a group of people to labor? It is just that a discerning person will grasp the fundamentals of gains and losses, knowing that laboring himself is nonetheless the way to leisure himself, will not complain to himself. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In recent days, mulberry trees and Manchurian walnut trees around the royal tombs got insect damages. So I commanded those magistrates of ten eup (prefectures) where the trees were planted to lead their local servants to capture and remove these insects, under the rationale of perpetual comfort with a short labor. However, the servants affiliated to the offices are also my people. Having in mind them laboring under the scorching sun, I am about to forget [desires] to sleep and eat. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Based on the line of Ouyang Xiu’s poem, “With twenty official coins [paid] per du [of insects], the piled harvest is like a mountain of grains,” a model of purchasing insects was specially created, luckily doing half the work and doubling the achievement. But in my heart I have something I cannot comfort myself with. These insects--despite having no such contribution as that of bees or silkworms and their malice being severer than that of mosquitos or horseflies--are still squirmy living things, too. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In accordance to the moral principle of a sage [saying], “Record the merit and reveal the harm,” we may certainly catch and eliminate them. When removing them, there ought to be a suitable way. We should make an order saying that the virtue of sparing life goes hand in hand with removing them but not [just] saying that they are harmful/Nobody should say that these insects are harmful. There are distinctive gaps of magnitude stemming from what they are as creatures. Driving them away into the marshland is better than being severe and burning them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Moreover, the line “lay hold of them and put them [in the blazing fire]” is just a talk/an expression. Burning and burying them was a real practice. The difference between the antiquity and the later era can be sufficiently observed. Earlier on, I heard that insects flying into the sea turned into fish or shrimps--it is [a story] about General Fubo governing Wuling which is still passed on as an explicit manifestation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For many days, I submerged myself to/deeply delve [into the matter] and decided to pronounce a decree: From now on, collect and throw them at Gupo. The distance to the estuary/inlet is not far away from where trees are planted, in close distance of 20 li. Purchasing insects reduces human labor and throwing them into the sea is narrated in tales (the precedent), what contradiction to righteousness could there be? | ||

| + | |||

| + | I summoned the magistrates to convey my intention in person and the trees at the tomb of Yeogang (present-day Yeoju), too, were certainly damaged by the insects. Purchasing insects and throwing them into water are based on the newly promulgated regulation of Hwaseong. I am sure, by not even a slightest means, that applying this [method] will not do. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I carried on to read the provincial governors’ account, telling that “catching them completely seems so out of reach for the time being and having people to labor at this season hinders the duty of agriculture.” I could not bear the thoughts glowing in mind that I called out for/lighted candles to issue a written instruction. Then I immediately ordered the court to lightningly notify the instruction to the provincial governors pertinent to this matter so from now on all the rest will be made regular businesses. Instruct [as such] to the Ministry of Rites and the Hanseong Magistracy. | ||

| + | |||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | ○傳曰: “蟲損嘉禾宰樹, 安得不捕, 而除之? | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [ordinance] message says: | ||

| + | Insects are reducing/damaging fine crops and noble trees [around royal tombs]. How could we not capture and eliminate them? | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 攷之經史自昔伊然, 周官庶氏, 剪氏之職, 皆爲是而設耳. 食苗者螟, 食葉者螣, 食根者蟊, 食節者賊. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Looking into the classics and history, from the past there had been such positions as that of Mr. Shu and Mr. Jian in “Zhouguan,” all installed for such work. Those feeding on sprouts are myeong (myŏng 螟), those feeding on leaves are teuk (tŭk 螣), those feeding on roots are mo 蟊, and those feeding on joints are jeok (jŏk 賊). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 秉畀炎火, 祝于田祖之神, 掘坑焚瘞, 行於唐時姚崇, 歷代因之, 遂爲成憲, 皆用民力. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Laying hold of them and throwing them into flames is to pray to the spirit of the Father of Husbandry. Digging down pits to incinerate and bury them has been practiced from Yao Chong (650-721) in the Tang period. The dynasties of the past eventually had laws established based on this, all using people’s labor. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 紫陽之訓有云, ‘豈能不役人, 徒而坐致成功?’ 但有見識人, 見得利害之實, 知其勞我者, 乃所以逸我, 自不怨耳. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As mentioned in Ziyang’s teachings, “How can one stay seated towards the success without getting a group of people to labor? It is just that a discerning person will grasp the fundamentals of gains and losses, knowing that laboring himself is nonetheless the way to leisure himself, will not complain to himself. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 近者園寢桑梓, 有蟲損之害, 使植木十邑守宰, 率官隷捕除之, 以寓暫勞永逸之意, 而官隷亦民也. 念其烈陽使役, 殆忘寢食. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In recent days, mulberry trees and Manchurian walnut trees around the royal tombs got insect damages. So I commanded those magistrates of ten eup (prefectures) where the trees were planted to lead their local servants to capture and remove these insects, under the rationale of perpetual comfort with a short labor. However, the servants affiliated to the offices are also my people. Having in mind them laboring under the scorching sun, I am about to forget [desires] to sleep and eat. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 乃引歐陽脩詩: ‘官錢二十買一斗, 頃刻露積如京坻.’ 之句, 特創買蟲之式, 幸得事半而功倍, 於予心猶有不自安者. 是蟲也, 雖蔑蜂蠶之功, 較甚蚊蝱之毒. 然且卽亦蠢動之生物也. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Based on the line of Ouyang Xiu’s poem, “With twenty official coins [paid] per du [of insects], the piled harvest is like a mountain of grains,” a model of purchasing insects was specially created, luckily doing half the work and doubling the achievement. But in my heart I have something I cannot comfort myself with. These insects--despite having no such contribution as that of bees or silkworms and their malice being severer than that of mosquitos or horseflies--are still squirmy living things, too. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 遵聖人錄其功明其毒之義, 固可捕而除之, 除之之際, 亦應有方便之方. 宜令曰, 生之德, 竝行於其間, 莫曰爲害, 隨其爲物而有巨細之各異, 驅而放菹, 勝於烈而焚之. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (ver.1) In accordance to the moral principle of a sage [saying], “Record the merit and reveal the harm,” we may certainly catch and eliminate them. When removing them, there ought to be a suitable way. We should make an order saying that the virtue of sparing life goes hand in hand with removing them but not saying that each of their harmfulness has distinctive gaps of magnitude stemming from what they are as creatures. Driving them away into the marshland is better than being severe and burning them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (ver. 2) In accordance to the moral principle of a sage [saying], “Record the merit and reveal the harm,” we may certainly catch and eliminate them. When removing them, there ought to be a suitable way. We should make an order saying that the virtue of sparing life goes hand in hand with removing them but not [just] saying that they are harmful. There are distinctive gaps of magnitude stemming from what they are as creatures. Driving them away into the marshland is better than being severe and burning them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 況秉畀之詠, 托(託)辭也, 焚瘞之擧, 實事也, 邃古後世之別, 亦足可觀. 嘗聞蟲飛入海, 化爲魚蝦, 伏波之治武陵, 明驗尙傳. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Moreover, the line “lay hold of them and put them [in the blazing fire]” is just a talk/an expression. Burning and burying them was a real practice. The difference between the antiquity and the later era can be sufficiently observed. Earlier on, I heard that insects flying into the sea turned into fish or shrimps--it is [a story] about General Fubo governing Wuling which is still passed on as an explicit manifestation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 多日潛究, 決意著令. 此後拾投鷗浦, 海口浦之距, 植木所不遠, 而近爲二十里. 買蟲省人力, 投海述故事, 於義有何悖乎? | ||

| + | |||

| + | For many days, I submerged myself to (deeply delve) delve [into the matter] and decided to pronounce a decree: From now on, collect and throw them at Gupo. The distance to the estuary/inlet is not far away from where trees are planted, in close distance of 20 li. Purchasing insects reduces human labor and throwing them into the sea is narrated in tales (the precedent), what contradiction to righteousness could there be? | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 召見守臣, 面諭此意, 而又於驪江陵樹, 亦云蟲損. 買蟲與投水, 一依華城新頒式令. 用之, 而決知其毫無不可. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I summoned the magistrates to convey my intention in person and the trees at the tomb of Yeogang (present-day Yeoju), too, were certainly damaged by the insects. Purchasing insects and throwing them into water are based on the newly promulgated regulation of Hwaseong. I am sure, by not even a slightest means, that applying this [method] will not do. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 續見道伯之狀語, 畢拾姑杳然, 比時役民, 有妨農政. 不勝耿耿, 呼燭書下. 卽令廟堂, 星火知委該道, 而今後餘皆以爲例事. 分付禮曹, 漢城府.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | I carried on to read the provincial governors’ account, telling that “catching them completely seems so out of reach for the time being and having people to labor at this season hinders the duty of agriculture.” I could not bear the thoughts glowing in mind that I called out for ( lighted ) candles to issue a written instruction. Then I immediately ordered the court to lightningly notify the instruction to the provincial governors pertinent to this matter so from now on all the rest will be made regular businesses / exemplar. Instruct [as such] to the Ministry of Rites and the Hanseong Magistracy. | ||

=='''Discussion Questions'''== | =='''Discussion Questions'''== | ||

| − | + | 1. What references are being used by the king? And from which periods are those references? | |

| − | |||

| + | 2. What kind of insects was in the citation of the poet from Ouyang Xiu? What are the insects in this text? Which insect is the main focus of this text? | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3. Does King Jeongjo’s compassion on the living reflect his turn on Buddhism in his last years? | ||

=='''Further Readings'''== | =='''Further Readings'''== | ||

| 57번째 줄: | 142번째 줄: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

--> | --> | ||

| − | + | (1) 정조실록 48권, 정조 22년 4월 25일 己未 2번째기사 1798년 청 가경(嘉慶) 3년 | |

| − | + | ||

| + | http://sillok.history.go.kr/id/wva_12204025_002 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | (2) 승정원일기 1791책 (탈초본 94책) 정조 22년 4월 25일 기미 16/18 기사 1798년 嘉慶(淸/仁宗) 3년 | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://sjw.history.go.kr/id/SJW-G22040250-01600 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | (3) 비변사등록 > 국역비변사등록 187책 > 정조 22년 1798년 04월25일(음) | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://db.history.go.kr/item/compareViewer.do;jsessionid=ACC2B2F0A65BE12D7437FB34983A46C8?levelId=bb_187r_001_04_0350 | ||

| + | |||

| + | (4) 정조실록 1권, 정조 대왕 행장(行狀) | ||

| + | http://sillok.history.go.kr/id/wva_200008 | ||

| + | <!-- | ||

=='''References'''== | =='''References'''== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| 158번째 줄: | 258번째 줄: | ||

[[Category:2018 Hanmun Summer Workshop]] | [[Category:2018 Hanmun Summer Workshop]] | ||

[[Category:Advanced Translation Group]] | [[Category:Advanced Translation Group]] | ||

| + | --> | ||

2022년 2월 14일 (월) 23:55 기준 최신판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | Ordinance on Removing Pests | |

| Chinese | 除蟲傳敎 | |

| Korean(RR) | 제충전교(Jechungjeongyo) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Royal Documents | |

| Type | Decree | |

| Author(s) | King Jeongjo (r. 1776-1800) | |

| Year | 1798 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | ordinance, royal tombs, insects, Confucian thoughts and locus, benevolence | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Ji-Hyun Lee, Sanghoon Na, Goeun Lee, Meng-Heng Lee | |

| Editor(s) | Ji-Hyun Lee | |

| Year | 2018 | |

Introduction

This ordinance by King Jeongjo is to remove the bugs from the royal tombs. It shows the king's decision of how to deal with those insects that damage the trees planted around the graveyards: hiring people to catch pests and, in turn, driving them into marshland rather than burning them to death. By revealing the ruler’s logic of why he raised the alternative, this text also reflects his being influenced by Neo-Confucianism.

In 1798, King Jeongjo learned that the trees growing around royal tombs were damaged by insects. After receiving this information, the king initially ordered the authorities to catch the bugs, trying to bring the lasting peace to his deceased ancestors with officials’ physical work, namely, catching the pests and then burning them as precedents in Tang China showed. However, he quickly realized that officials were also his people, of whom he should take care, and whose working force should not be abused. The ruler of the Joseon dynasty then changed his mind. He decided to financially reward the subjects who gathered the harmful creatures. And, instead of burning them, he also commanded administrations to drive those noxious beings into marshland, showing his respect to the righteousness and Heaven’s virtue of sparing lives. His shift between the two plans in this ordinance laid out the Neo-Confucianized mentality of a Joseon king.

The structure of this ordinance was built on Confucian thoughts and locus. This text began with the king’s highlighting the damage that the bugs cause. To show his reasoning for considering removing the harmful creatures, the ruler referred to several sources, such as the Classic of Poetry, the Rites of Zhou, and the sayings from Zhu Xi. However, the king raised another idea when he thought he should also treat the officials working for him well. To rationalize his reconsideration of the solution, he cited sentences from a poem written by Ouyang Xiu, the Compendium of Materia Medica, Taiping Yulan, and the Classic of Poetry. By utilizing some locus supporting the banishment of the pests to challenge others justifying the execution of burning, at the end of this decree, King Jeongjo adopted the plans of purchasing insects and throwing them to marshlands and commanded his ministers to institutionalize the policies as what had been shown in the previous legal promulgation.

The importance of this document is: 1. It manifests the heavy reliance of Joseon court on Confucian ideals and ancient tradition because

1-1. the king and his subjects are referring to Confucian writings even for matters dealing with insects (經史, 紫陽之訓, 歐陽脩詩) 1-2. the king was concerned about ethics even for killing insects (生之德並行於其間, 於義有何悖乎). > the king’s care for the dead and the living (both people and insects)

2. This document shows the Confucian transfer of attitude toward the removal of pests 除蟲, which is quite different from the early Joseon dynasty (cf.세종실록 113권, 세종 28년 7월 15일 신사 1번째기사 (1446) http://sillok.history.go.kr/id/kda_12807015_001)

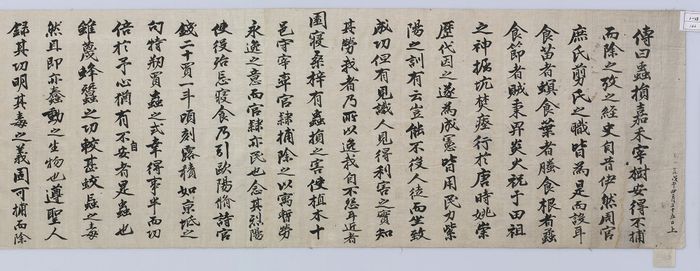

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

正祖戊午四月二十五日上 傳曰 蟲損嘉禾宰樹 安得不捕而除之 攷之經史 自昔伊然 周官庶氏剪氏之職 皆爲是而設耳 食苗者螟 食葉者螣 食根者蟊 食節者賊 秉畀炎火 祝于田祖之神 掘坑焚瘞 行於唐時姚崇 歷代因之 遂爲成憲 皆用民力 紫陽之訓有云 豈能不役人徒 而坐致成功 但有見識人 見得利害之實 知其勞我者 乃所以逸我自不怨耳 近者 園寢桑梓 有蟲損之害 使植木 十邑守宰 率官隷捕除之 以寓暫勞永逸之意 而官隷亦民也 念其烈陽使役 殆忘寢食 乃引歐陽脩詩 官錢二十買一斗 頃刻露積如京坻之句 特刱買蟲之式 幸得事半而功倍 於予心猶有不自安者 是蟲也 雖蔑蜂蠶之功 較甚蚊蝱之毒 然且卽亦蠢動之生物也 遵聖人錄其功明其毒之義 固可捕而除之 除之之際 亦應有方便之方 宜令曰 生之德並行於其間 莫曰爲害 隨其爲物而有巨細之各異 驅而放菹 勝於烈而焚之 況秉畀之詠托辭也 焚瘞之擧實事也 邃古後世之別 亦足可觀 嘗聞蟲飛入海 化爲魚蝦 伏波之治 武陵明驗尙傳 多日潛究 決意著令 此後拾投鷗浦海口 浦之距植木所不遠 而近爲二十里 買蟲省人力 投海述故事 於義有何悖乎 召見守臣 面諭此意 而又於驪江陵樹亦云蟲損 買蟲與投水 一依華城新頒式令用之 決知其毫無不可 續見道伯之狀語 畢拾姑杳然 此時役民有妨農政 不勝耿耿 呼燭書下 卽令廟堂 星火知委該道 而今後餘皆以爲例事 分付禮曹漢城府

|

(Translation) The [ordinance] message says: Insects are reducing/damaging fine crops and noble trees [around royal tombs]. How could we not capture and eliminate them? Looking into the classics and history, from the past there had been such positions as that of Mr. Shu and Mr. Jian in “Zhouguan,” all installed for such work. Those feeding on sprouts are myeong (myŏng 螟), those feeding on leaves are teuk (tŭk 螣), those feeding on roots are mo 蟊, and those feeding on joints are jeok (jŏk 賊). Laying hold of them and throwing them into flames is to pray to the spirit of the Father of Husbandry. Digging down pits to incinerate and bury them has been practiced from Yao Chong (650-721) in the Tang period. The dynasties of the past eventually had laws established based on this, all using people’s labor. As mentioned in Ziyang’s teachings, “How can one stay seated towards the success without getting a group of people to labor? It is just that a discerning person will grasp the fundamentals of gains and losses, knowing that laboring himself is nonetheless the way to leisure himself, will not complain to himself. In recent days, mulberry trees and Manchurian walnut trees around the royal tombs got insect damages. So I commanded those magistrates of ten eup (prefectures) where the trees were planted to lead their local servants to capture and remove these insects, under the rationale of perpetual comfort with a short labor. However, the servants affiliated to the offices are also my people. Having in mind them laboring under the scorching sun, I am about to forget [desires] to sleep and eat. Based on the line of Ouyang Xiu’s poem, “With twenty official coins [paid] per du [of insects], the piled harvest is like a mountain of grains,” a model of purchasing insects was specially created, luckily doing half the work and doubling the achievement. But in my heart I have something I cannot comfort myself with. These insects--despite having no such contribution as that of bees or silkworms and their malice being severer than that of mosquitos or horseflies--are still squirmy living things, too. In accordance to the moral principle of a sage [saying], “Record the merit and reveal the harm,” we may certainly catch and eliminate them. When removing them, there ought to be a suitable way. We should make an order saying that the virtue of sparing life goes hand in hand with removing them but not [just] saying that they are harmful/Nobody should say that these insects are harmful. There are distinctive gaps of magnitude stemming from what they are as creatures. Driving them away into the marshland is better than being severe and burning them. Moreover, the line “lay hold of them and put them [in the blazing fire]” is just a talk/an expression. Burning and burying them was a real practice. The difference between the antiquity and the later era can be sufficiently observed. Earlier on, I heard that insects flying into the sea turned into fish or shrimps--it is [a story] about General Fubo governing Wuling which is still passed on as an explicit manifestation. For many days, I submerged myself to/deeply delve [into the matter] and decided to pronounce a decree: From now on, collect and throw them at Gupo. The distance to the estuary/inlet is not far away from where trees are planted, in close distance of 20 li. Purchasing insects reduces human labor and throwing them into the sea is narrated in tales (the precedent), what contradiction to righteousness could there be? I summoned the magistrates to convey my intention in person and the trees at the tomb of Yeogang (present-day Yeoju), too, were certainly damaged by the insects. Purchasing insects and throwing them into water are based on the newly promulgated regulation of Hwaseong. I am sure, by not even a slightest means, that applying this [method] will not do. I carried on to read the provincial governors’ account, telling that “catching them completely seems so out of reach for the time being and having people to labor at this season hinders the duty of agriculture.” I could not bear the thoughts glowing in mind that I called out for/lighted candles to issue a written instruction. Then I immediately ordered the court to lightningly notify the instruction to the provincial governors pertinent to this matter so from now on all the rest will be made regular businesses. Instruct [as such] to the Ministry of Rites and the Hanseong Magistracy. |

○傳曰: “蟲損嘉禾宰樹, 安得不捕, 而除之?

The [ordinance] message says: Insects are reducing/damaging fine crops and noble trees [around royal tombs]. How could we not capture and eliminate them?

攷之經史自昔伊然, 周官庶氏, 剪氏之職, 皆爲是而設耳. 食苗者螟, 食葉者螣, 食根者蟊, 食節者賊.

Looking into the classics and history, from the past there had been such positions as that of Mr. Shu and Mr. Jian in “Zhouguan,” all installed for such work. Those feeding on sprouts are myeong (myŏng 螟), those feeding on leaves are teuk (tŭk 螣), those feeding on roots are mo 蟊, and those feeding on joints are jeok (jŏk 賊).

秉畀炎火, 祝于田祖之神, 掘坑焚瘞, 行於唐時姚崇, 歷代因之, 遂爲成憲, 皆用民力.

Laying hold of them and throwing them into flames is to pray to the spirit of the Father of Husbandry. Digging down pits to incinerate and bury them has been practiced from Yao Chong (650-721) in the Tang period. The dynasties of the past eventually had laws established based on this, all using people’s labor.

紫陽之訓有云, ‘豈能不役人, 徒而坐致成功?’ 但有見識人, 見得利害之實, 知其勞我者, 乃所以逸我, 自不怨耳.

As mentioned in Ziyang’s teachings, “How can one stay seated towards the success without getting a group of people to labor? It is just that a discerning person will grasp the fundamentals of gains and losses, knowing that laboring himself is nonetheless the way to leisure himself, will not complain to himself.

近者園寢桑梓, 有蟲損之害, 使植木十邑守宰, 率官隷捕除之, 以寓暫勞永逸之意, 而官隷亦民也. 念其烈陽使役, 殆忘寢食.

In recent days, mulberry trees and Manchurian walnut trees around the royal tombs got insect damages. So I commanded those magistrates of ten eup (prefectures) where the trees were planted to lead their local servants to capture and remove these insects, under the rationale of perpetual comfort with a short labor. However, the servants affiliated to the offices are also my people. Having in mind them laboring under the scorching sun, I am about to forget [desires] to sleep and eat.

乃引歐陽脩詩: ‘官錢二十買一斗, 頃刻露積如京坻.’ 之句, 特創買蟲之式, 幸得事半而功倍, 於予心猶有不自安者. 是蟲也, 雖蔑蜂蠶之功, 較甚蚊蝱之毒. 然且卽亦蠢動之生物也.

Based on the line of Ouyang Xiu’s poem, “With twenty official coins [paid] per du [of insects], the piled harvest is like a mountain of grains,” a model of purchasing insects was specially created, luckily doing half the work and doubling the achievement. But in my heart I have something I cannot comfort myself with. These insects--despite having no such contribution as that of bees or silkworms and their malice being severer than that of mosquitos or horseflies--are still squirmy living things, too.

遵聖人錄其功明其毒之義, 固可捕而除之, 除之之際, 亦應有方便之方. 宜令曰, 生之德, 竝行於其間, 莫曰爲害, 隨其爲物而有巨細之各異, 驅而放菹, 勝於烈而焚之.

(ver.1) In accordance to the moral principle of a sage [saying], “Record the merit and reveal the harm,” we may certainly catch and eliminate them. When removing them, there ought to be a suitable way. We should make an order saying that the virtue of sparing life goes hand in hand with removing them but not saying that each of their harmfulness has distinctive gaps of magnitude stemming from what they are as creatures. Driving them away into the marshland is better than being severe and burning them.

(ver. 2) In accordance to the moral principle of a sage [saying], “Record the merit and reveal the harm,” we may certainly catch and eliminate them. When removing them, there ought to be a suitable way. We should make an order saying that the virtue of sparing life goes hand in hand with removing them but not [just] saying that they are harmful. There are distinctive gaps of magnitude stemming from what they are as creatures. Driving them away into the marshland is better than being severe and burning them.

況秉畀之詠, 托(託)辭也, 焚瘞之擧, 實事也, 邃古後世之別, 亦足可觀. 嘗聞蟲飛入海, 化爲魚蝦, 伏波之治武陵, 明驗尙傳.

Moreover, the line “lay hold of them and put them [in the blazing fire]” is just a talk/an expression. Burning and burying them was a real practice. The difference between the antiquity and the later era can be sufficiently observed. Earlier on, I heard that insects flying into the sea turned into fish or shrimps--it is [a story] about General Fubo governing Wuling which is still passed on as an explicit manifestation.

多日潛究, 決意著令. 此後拾投鷗浦, 海口浦之距, 植木所不遠, 而近爲二十里. 買蟲省人力, 投海述故事, 於義有何悖乎?

For many days, I submerged myself to (deeply delve) delve [into the matter] and decided to pronounce a decree: From now on, collect and throw them at Gupo. The distance to the estuary/inlet is not far away from where trees are planted, in close distance of 20 li. Purchasing insects reduces human labor and throwing them into the sea is narrated in tales (the precedent), what contradiction to righteousness could there be?

召見守臣, 面諭此意, 而又於驪江陵樹, 亦云蟲損. 買蟲與投水, 一依華城新頒式令. 用之, 而決知其毫無不可.

I summoned the magistrates to convey my intention in person and the trees at the tomb of Yeogang (present-day Yeoju), too, were certainly damaged by the insects. Purchasing insects and throwing them into water are based on the newly promulgated regulation of Hwaseong. I am sure, by not even a slightest means, that applying this [method] will not do.

續見道伯之狀語, 畢拾姑杳然, 比時役民, 有妨農政. 不勝耿耿, 呼燭書下. 卽令廟堂, 星火知委該道, 而今後餘皆以爲例事. 分付禮曹, 漢城府.”

I carried on to read the provincial governors’ account, telling that “catching them completely seems so out of reach for the time being and having people to labor at this season hinders the duty of agriculture.” I could not bear the thoughts glowing in mind that I called out for ( lighted ) candles to issue a written instruction. Then I immediately ordered the court to lightningly notify the instruction to the provincial governors pertinent to this matter so from now on all the rest will be made regular businesses / exemplar. Instruct [as such] to the Ministry of Rites and the Hanseong Magistracy.

Discussion Questions

1. What references are being used by the king? And from which periods are those references?

2. What kind of insects was in the citation of the poet from Ouyang Xiu? What are the insects in this text? Which insect is the main focus of this text?

3. Does King Jeongjo’s compassion on the living reflect his turn on Buddhism in his last years?

Further Readings

(1) 정조실록 48권, 정조 22년 4월 25일 己未 2번째기사 1798년 청 가경(嘉慶) 3년

http://sillok.history.go.kr/id/wva_12204025_002

(2) 승정원일기 1791책 (탈초본 94책) 정조 22년 4월 25일 기미 16/18 기사 1798년 嘉慶(淸/仁宗) 3년

http://sjw.history.go.kr/id/SJW-G22040250-01600

(3) 비변사등록 > 국역비변사등록 187책 > 정조 22년 1798년 04월25일(음)

(4) 정조실록 1권, 정조 대왕 행장(行狀)