"(Translation) 儒胥必知凡例"의 두 판 사이의 차이

Sanghoon Na (토론 | 기여) 잔글 |

Sanghoon Na (토론 | 기여) 잔글 |

||

| (같은 사용자의 중간 판 7개는 보이지 않습니다) | |||

| 40번째 줄: | 40번째 줄: | ||

| − | There are several different styles of writing. | + | There are several different styles of writing. Authors place a particular value on the literary style. Examinees learn to practice the writing styles for state examinations. Clerical workers practice a clerk’s writing style. |

| 168번째 줄: | 168번째 줄: | ||

凡文字之體 各自不同 爲文章之學者尙文章之體 爲功令之學者 習功令之體 爲吏胥之學者 講吏胥之體 | 凡文字之體 各自不同 爲文章之學者尙文章之體 爲功令之學者 習功令之體 爲吏胥之學者 講吏胥之體 | ||

| − | There are several different styles of writing. | + | There are several different styles of writing. Authors place a particular value on the literary style. Examinees learn to practice the writing styles for state examinations. Clerical workers practice a clerk’s writing style. |

所謂文章之學者 序∙記∙跋∙雜著等體也 所謂功令之學者 詩∙賦∙表∙策∙疑∙義等體也 所謂吏胥之學者 非獨文簿而已 上言∙所志∙議送等體 皆是吏胥之不可不知者 又非獨吏胥之所可知也 凡爲吏治者 亦不可不知者 然此等文字 於儒胥最近 故名之曰儒胥必知 而其法例 一一列之於左 | 所謂文章之學者 序∙記∙跋∙雜著等體也 所謂功令之學者 詩∙賦∙表∙策∙疑∙義等體也 所謂吏胥之學者 非獨文簿而已 上言∙所志∙議送等體 皆是吏胥之不可不知者 又非獨吏胥之所可知也 凡爲吏治者 亦不可不知者 然此等文字 於儒胥最近 故名之曰儒胥必知 而其法例 一一列之於左 | ||

| − | Literary writings refer to a preface, a journal, a postface, miscellaneous works, and so on. Exam writings refer to poetry, rhymeprose, a memorial,<ref> A memorial | + | Literary writings refer to a preface, a journal, a postface, miscellaneous works, and so on. Exam writings refer to poetry, rhymeprose,<ref> Rhyme-prose (''fu'' 賦) was a major poetic form in Chinese literature, most popular between the 2nd century BCE and 6th century CE. It is a hybrid of prose and rhymed verse, more expansive than the condensed lyrics.</ref> a memorial,<ref> A memorial (''biao'' 表) was a document presented by officials to the king or the emperor. It could be a statement of facts addressed to a government and often accompanied by a petition or remonstrance.</ref> a problem essay,<ref> A problem essay (''chaek'' 策) was a type of the state examination, which included comments on political matters and applied interpretations of quotations from the Confucian Classics.</ref> an explication,<ref> An explication (''ui'' 疑) refers to the clarification of doubtful points in the passages from the Confucian Classics.</ref> This refers to the interpretation of passages from the Classics.</ref> etc. Clerical writings refer to not only official documents and ledgers but also private requests, petitions, letters of appeal, and others. All of these writings are what clerks must know. Not merely do the clerks have to know but also governors ought to know them. However, these kinds of writings are mostly used by scholars and clerks, therefore this book is titled the Essential Knowledge for Literati and Clerks. The exemplary format for each document is provided individually as follows: |

| 208번째 줄: | 208번째 줄: | ||

一 女人呈訴 則始面云 某地居某召史 [如金姓人則曰金召史 李姓人則曰李召史 各隨其姓] 白活 起頭與結辭上同 [自稱其身曰矣女] | 一 女人呈訴 則始面云 某地居某召史 [如金姓人則曰金召史 李姓人則曰李召史 各隨其姓] 白活 起頭與結辭上同 [自稱其身曰矣女] | ||

| − | One: If a woman submits a petition, she should write the following phrase on the first page: “The ''balgwal'' of a certain woman (joy 召史) living in a certain area.” [If her family name is Kim, she is Kim joy. If Yi, then Yi joy. Each follows her family name.] The opening and closing lines are the same as above. [She should refer to herself as ''ui-nyeo'' 矣女 (“I, a woman”).] | + | One: If a woman submits a petition, she should write the following phrase on the first page: “The ''balgwal'' of a certain woman (''joy'' 召史) living in a certain area.” [If her family name is Kim, she is Kim ''joy''. If Yi, then Yi ''joy''. Each follows her family name.] The opening and closing lines are the same as above. [She should refer to herself as ''ui-nyeo'' 矣女 (“I, a woman”).] |

| 228번째 줄: | 228번째 줄: | ||

一 謄書之際 上於平行者及上於二字者 皆依其法 使人無昧禮之嘆 | 一 謄書之際 上於平行者及上於二字者 皆依其法 使人無昧禮之嘆 | ||

| − | One: When this book was edited, certain characters were designed to be arranged one or two lines above the others according to the rule<ref> This rule is called ''daedubeop'' 擡頭法 (“rule of raising a head”), which was applied to characters indicating a king (sang 上) or a magistrate (''gwan'' 官).</ref> in order to prevent readers from sighing at the author’s ignorance of the appropriate custom. | + | One: When this book was edited, certain characters were designed to be arranged one or two lines above the others according to the rule<ref> This rule is called ''daedubeop'' 擡頭法 (“rule of raising a head”), which was applied to characters indicating a king (''sang'' 上) or a magistrate (''gwan'' 官).</ref> in order to prevent readers from sighing at the author’s ignorance of the appropriate custom. |

| 243번째 줄: | 243번째 줄: | ||

一 文券套 | 一 文券套 | ||

| − | One: The format for writing a deed ('' | + | One: The format for writing a deed (''mun'gwon'' 文券) is introduced. |

| 253번째 줄: | 253번째 줄: | ||

儒胥必知凡例終 | 儒胥必知凡例終 | ||

| − | The general guideline for the ''Essential Knowledge for Literati and Clerks'' is hereby concluded. | + | The general guideline for the ''Essential Knowledge for Literati and Clerks'' is hereby concluded. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=='''Further Readings'''== | =='''Further Readings'''== | ||

| 269번째 줄: | 265번째 줄: | ||

* 김봉좌,『유서필지』 판본 연구, 서지학보29, 2005. | * 김봉좌,『유서필지』 판본 연구, 서지학보29, 2005. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =='''Footnotes'''== | ||

2018년 9월 30일 (일) 14:33 기준 최신판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | General Introduction of the Essential Knowledge for Literati and Clerks | |

| Chinese | 儒胥必知凡例 | |

| Korean(RR) | 유서필지범례(Yuseo pilji beomnye) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Literati Writings | |

| Type | Manual | |

| Author(s) | Anonymous | |

| Year | ca. 1800 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | clerks, idu ("clerk readings"), document forms | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | Sanghoon Na | |

| Year | 2018 | |

목차

Introduction

Original Script

- Discussion Questions:

Annotated Interlinear Translation

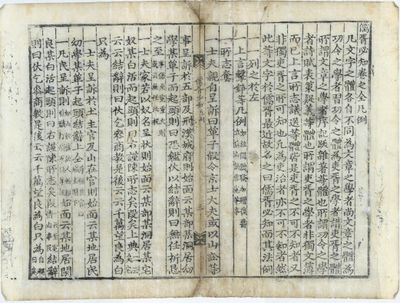

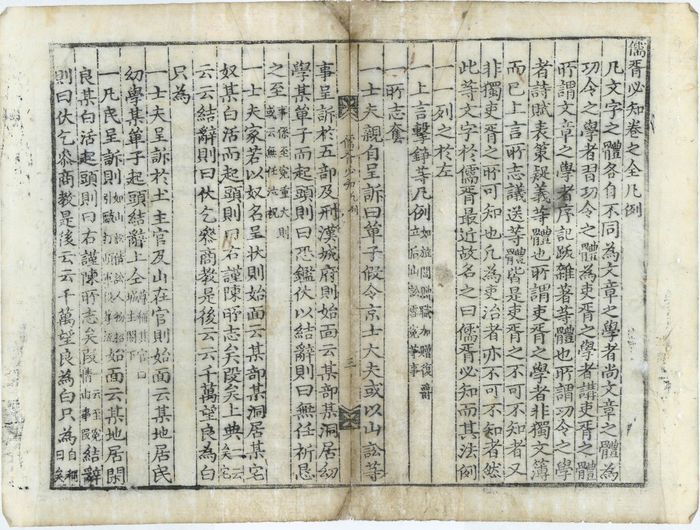

儒胥必知 凡例

General Guideline for the Essential Knowledge for Literati and Clerks

凡文字之體 各自不同 爲文章之學者尙文章之體 爲功令之學者 習功令之體 爲吏胥之學者 講吏胥之體

There are several different styles of writing. Authors place a particular value on the literary style. Examinees learn to practice the writing styles for state examinations. Clerical workers practice a clerk’s writing style.

所謂文章之學者 序∙記∙跋∙雜著等體也 所謂功令之學者 詩∙賦∙表∙策∙疑∙義等體也 所謂吏胥之學者 非獨文簿而已 上言∙所志∙議送等體 皆是吏胥之不可不知者 又非獨吏胥之所可知也 凡爲吏治者 亦不可不知者 然此等文字 於儒胥最近 故名之曰儒胥必知 而其法例 一一列之於左

Literary writings refer to a preface, a journal, a postface, miscellaneous works, and so on. Exam writings refer to poetry, rhymeprose,[1] a memorial,[2] a problem essay,[3] an explication,[4] This refers to the interpretation of passages from the Classics.</ref> etc. Clerical writings refer to not only official documents and ledgers but also private requests, petitions, letters of appeal, and others. All of these writings are what clerks must know. Not merely do the clerks have to know but also governors ought to know them. However, these kinds of writings are mostly used by scholars and clerks, therefore this book is titled the Essential Knowledge for Literati and Clerks. The exemplary format for each document is provided individually as follows:

一 上言擊錚等凡例 [如旌閭∙贈職∙加贈∙復爵∙立后∙山訟∙雪冤等事]

One: The general examples for written petitions (i.e. private requests) and oral petitions [5] are the documents asking for things like a memorial gate,[6] a posthumous title, an additional posthumous title, reinstatement, legal succession, burial site litigation, and a vindication.

一 所志套

One: The followings are formats for writing a petition.

一 士夫親自呈訴曰單子 假令京士大夫或以山訟等事 呈訴於五部及刑∙漢城府 則始面云某部某洞居幼 學某單子 而起頭則 曰恐鑑伏以 結辭則曰無任祈懇之至 [事係至寃重大 則或云無任泣祝]

One: A petition that a scholar submits himself is called danja 單子 (“a piece of note”). If a scholar in Seoul submits a petition to the Five Wards, the Board of Punishments, or the Seoul Magistracy because of the matters like burial site litigation, he should write the following phrase on the first page: “The danja of a certain scholar living in a certain town in a certain district.” For the opening line, state this: “I prostrate myself to ask you to take a look at this case.” For the closing line, write this: “I cannot help earnestly making a request with my utmost sincerity.” [If the matter is extremely grievous and grave, say this: “I cannot help but pray to you with tears.”]

一 士夫家若以奴名呈狀 則始面云某部某洞居某宅奴某白活 而起頭則曰右謹陳所志矣段 矣上典 [一云矣宅]云云 結辭則曰伏乞參商敎是後云云 千萬望良爲白只爲

One: If a member of a scholar’s family submits a petition in the name of his slave, he should write the following phrase on the first page: “The balgwal 白活 (“plea”) of a certain slave living in a certain family in a certain town in a certain district.” For the opening line, write this: “I reverentially submit this petition as follows: My master [or my master’s family] ….” For the closing line, write this: “I prostrate myself to beg you to consider this, and then… I wish ten thousand times for this.”

一 士夫呈訴於土主官及山在官 則始面云某地居民幼學某單子 起頭∙結辭 上同 [尊稱其官曰城主閤下]

One: If a scholar submits a petition to the magistrate in his town or to the magistrate in another town where his ancestor’s grave is located, he should write the following phrase on the first page: “The danja of a certain scholar, a resident of a certain area.” The opening and closing lines are the same as above. [He should address his magistrate by the title seongju hapha 城主閤下 (“His Excellency the Lord of the Castle.”)

一 凡民呈訴 則 [如山訟∙債訟∙人物招引∙毆打∙頉軍役等流] 始面云某地居閑良某白活 起頭則曰右謹陳所志矣段 [一云至寃情由事段] 結辭則曰伏乞參商敎是後云云 千萬望良爲白只爲 [自稱曰矣身 尊稱其官曰使道主∙案前主 隨其官職之品秩]

One: If a commoner submits a petition because of matters like burial site litigation, debt litigation, human trafficking, assault and battery, or a military exemption, he should write the following phrase on the first page: “The balgwal of a certain commoner living in a certain area.” For the opening line, write this: “I reverentially submit the petition as follows.” [or I report the most grievous case as follows.] For the closing line, write this: “I prostrate myself to beg you to consider this case, and then… I wish ten thousand times for this.” [He should refer to himself as uisin 矣身 (“I, myself”) and address his magistrate by the title sadoju 使道主 (“commissioned lord of the province”) or anjeonju 案前主 (“lord sitting at the desk”) according to his rank.]

一 女人呈訴 則始面云 某地居某召史 [如金姓人則曰金召史 李姓人則曰李召史 各隨其姓] 白活 起頭與結辭上同 [自稱其身曰矣女]

One: If a woman submits a petition, she should write the following phrase on the first page: “The balgwal of a certain woman (joy 召史) living in a certain area.” [If her family name is Kim, she is Kim joy. If Yi, then Yi joy. Each follows her family name.] The opening and closing lines are the same as above. [She should refer to herself as ui-nyeo 矣女 (“I, a woman”).]

一 議送者 呈于監營之謂也 無論士夫及凡民 起訟於本官 而本官不能公決 則落訟者可以議送於營門也 若或不由本官 直呈營門 則營門不許聽理

One: An appeal letter (uisong 議送) refers to a petition submitted to a provincial governor’s office. Regardless of a person’s status, whether he is a scholar or a commoner, if anyone attempts to petition his local magistrate but is not treated fairly by him, he can submit an appeal letter to a provincial governor’s office. [However,] if the letter goes directly to the governor’s office and not through the magistrate in charge of the area, it will not be allowed to be heard or proceed.

一 議送之套 與所志大同小異 而始面云 某地居某 [隨其人書之] 議送

One: The format for writing an appeal letter is similar to that of a petition, but one should write the following phrase on the first page: “The appeal letter of a certain person [his name and status are placed here] living in a certain area.”

一 雖有凡例 不見專(全)篇 則猶有不能纖悉之慮 故先自上言∙原情 以至于所志∙議送 各立條目 詳著一篇 使蒙學之人有所參考焉

One: Although there is a general guideline, if one does not read the entire book, he will not be able to know the details, which is my concern. Therefore, I provide a detailed example of each document, ranging from a private request and a complaint to a petition and an appeal letter, for beginning readers so that they may consult it.

一 謄書之際 上於平行者及上於二字者 皆依其法 使人無昧禮之嘆

One: When this book was edited, certain characters were designed to be arranged one or two lines above the others according to the rule[7] in order to prevent readers from sighing at the author’s ignorance of the appropriate custom.

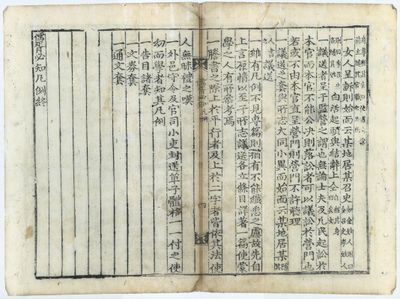

一 外邑守令及官司小吏封送單子 體格一一付之 使幼而學者 知其凡例

One: As for notes containing a list of items sent by magistrates in rural areas or of his clerks and petty officials, an exemplary format for each case is appended to it so that beginning readers may know the general principle.

一 告目諸套

One: The format for writing a letter to a superior (gomok 告目) is introduced here.

一 文券套

One: The format for writing a deed (mun'gwon 文券) is introduced.

一 通文套

One: The format for writing a circular letter (tongmun 通文) is introduced.

儒胥必知凡例終

The general guideline for the Essential Knowledge for Literati and Clerks is hereby concluded.

Further Readings

- 전경목 외, 유서필지, 사계절, 2006.

- 전경목, 19세기 『儒胥必知』 編刊의 특징과 의의, 장서각15, 2006.

- 김봉좌,『유서필지』 판본 연구, 서지학보29, 2005.

Footnotes

- ↑ Rhyme-prose (fu 賦) was a major poetic form in Chinese literature, most popular between the 2nd century BCE and 6th century CE. It is a hybrid of prose and rhymed verse, more expansive than the condensed lyrics.

- ↑ A memorial (biao 表) was a document presented by officials to the king or the emperor. It could be a statement of facts addressed to a government and often accompanied by a petition or remonstrance.

- ↑ A problem essay (chaek 策) was a type of the state examination, which included comments on political matters and applied interpretations of quotations from the Confucian Classics.

- ↑ An explication (ui 疑) refers to the clarification of doubtful points in the passages from the Confucian Classics.

- ↑ The Chinese characters for the oral petition are gyeokjaeng 擊錚, which literally means “striking a gong.” Through the gyeokjaeng system, commoners were allowed to strike a gong or drum in front of the palace or during the king’s public processions in order to appeal their grievances or petition to the king directly.

- ↑ The memorial gate (jeongnyeo 旌閭) was erected in honor of a person’s act of filial piety or chastity.

- ↑ This rule is called daedubeop 擡頭法 (“rule of raising a head”), which was applied to characters indicating a king (sang 上) or a magistrate (gwan 官).