Current Status of Korean Cultural Heritage Interpretation

The purpose of this section is to provide an overview of the current status of Korean cultural heritage interpretation. This includes a summary of the kinds and number of heritages designated by or registered with the Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), the various interpretive resources available to the public, the process by which on-site interpretive texts are composed and translated (including a translation of the official CHA guidelines for interpretive text composition and translation), as well as a detailed breakdown of the kind of content generally found in on-site interpretive texts.

Contents

Korean Cultural Heritages and Managing Institutions

In South Korea, cultural heritages are designated by or registered with the Cultural Heritage Administration, which is an affiliated institution of the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism. Cultural heritages can be designated at a state or city/province level, with seven classifications at the state level and four at the city/province level. There are also classifications for Registered Cultural Heritages, which generally includes heritages from the 20th century, and Cultural Heritage Material, which are not designated as heritages, but still deemed to have preservation value. In addition to this are heritages registered with UNESCO. The number of cultural heritages designated or registered (including Cultural Heritage Material) with the CHA are as follows[1]:

Table 9 Statistics on current CHA designated cultural heritages

| Designation Level | Designation | Number |

|---|---|---|

| State | National Treasure | 331 |

| Treasure | 2,067 | |

| Historic Site | 493 | |

| Scenic Site | 110 | |

| Natural Monument | 456 | |

| National Intangible Cultural Heritage | 140 | |

| National Folklore Cultural Heritage | 292 | |

| City/Province | Tangible Cultural Heritage | 3,099 |

| Intangible Cultural Heritage | 519 | |

| Monument | 1,706 | |

| Folklore Heritage | 467 | |

| - | Registered Cultural Heritage | 697 |

| - | Cultural Heritage Material | 2,593 |

| World | UNESCO Heritage | 44 |

| Total | 13,014 |

The cultural heritages themselves are diverse in nature. They include archeological sites, paintings, sculptures, architectural structures, song and dance traditions, old documents, and many more. In total, the CHA categorizes its heritages into 136 different categories[2]. This thesis will focus on on-site cultural heritages, an unofficial category created for the purposes of this thesis, which include those heritages that are tangible in nature and usually found at heritage sites (as opposed to museums).

Although cultural heritages are designated by or registered with the Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), the direct management of heritages is left up to institutions such as public and private museums and archives, which manage artifacts and old documents, special CHA-affiliated organizations for important historical sites such as the Joseon Royal Palaces and UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and local province, city, county and district governments (of which there are 250 in total), which manage most on-site heritages and the objects contained there within. These managing institutions are also responsible for the interpretive resources about the heritages they manage, namely the composition and translation of interpretive texts on information panels and brochures, as well as other interpretive resources such as tours, educational programs, events, audio-visual guides, etc. (explained further in the following section), although some online resources, video resources and children's resources are developed directly by the CHA. Other related institutions, which do not manage heritages but are involved in research about heritages, are the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, the Korea National University of Cultural Heritage, the Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation, and more.

Resources

As mentioned in the “Definitions of Other Key Terms” section, interpretive resources are comprised of content (a particular topic) presented via a medium. The mediums were explained in that section in terms of visual, auditory, and tactile, as well as linguistic and non-linguistic. However, for the purposes of this section, interpretive resources will be grouped into four categories based on the presentation technology: analog and digital (offline, online, and metadata). Analog resources include resources which are experienced in-person without a digital interface of any kind, such as visits to a heritage site, print media, in-person interpretations by tour guides, hands-on experiential activities, and in-person performances. Digital resources include resources which are experienced via a digital device, such as an audio device, video screen, mobile phone, tablet, or computer. These may include things such as audio device guided tours, touch-screen activity panels, photo, video, and text content presented via a digital screen, and augmented or virtual reality experiences. There are two subcategories of digital resources: offline and online. Online resources refer to a specific subset of digital resources which are connected to the Internet, and therefore, can utilize the power of the World Wide Web, such as the ability to search for further information. Furthermore, unlike offline resources, which are only available to those visiting the heritage site or museum in person, online resources can be accessed anywhere by anyone with an internet connection. Metadata is a subset of online resources, and for the purposes of this thesis, refers to the basic data which identifies and described each cultural heritage.

Most official interpretive resources for cultural heritages fall somewhere the umbrella of the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism (MCST), which includes the Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), the National Museum of Korea (NMK), the Korea Culture Information Service Agency (KCISA), as well as the Korea Tourism Organization (KTO). Official content also includes that provided by local governments, which are directly in charge of the management and interpretation of designated and registered cultural heritages within their jurisdiction. Other institutions which provide interpretive resources on cultural heritages are those such as Jangseogak Archives at the Academy of Korean Studies, Kyujanggak Archives at Seoul National University, among others. There are also private museums which hold many heritage artifacts, like the Leeum Museum or the Gansong Art Museum, which also have their own interpretive resources. There also may be “unofficial” interpretive resources available online and offline that are provided by private businesses, individual scholars, and hobbyists, ranging from books or blog posts to guided tours. For the purposes of this review, these “unofficial” resources will not be considered.

The research in this section was based on the information provided on the various websites of the organizations mentioned above as well as the personal experiences of the author visiting heritage sites and museums around Korea, and the brochures and photos of information panels collected and taken during those visits. Online material and apps were accessed in May 2017, while brochure materials were compiled between 2013 and 2017.

Analog

Let us first look at analog interpretive resources. These resources, available in-person at museums or heritage sites, include text or visual material (via stationary information panels and brochures/pamphlets which visitors can take with them), guided tours led and commentated by a tour guide, passive and active experiential activities (such as musical performances or hands-on activities such as craft making), libraries and museum shops, and educational and volunteer programs. The experience of being in the same physical space as the heritages can also be considered an interpretive resource of its own.

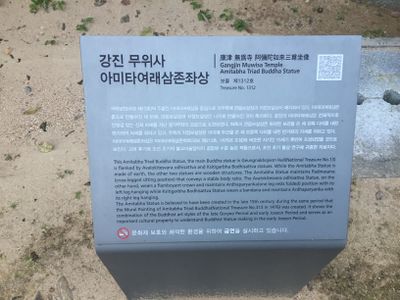

The most universally available analog resources are information panels and brochures. Most information panels include only interpretive texts, but some also include visual content such as diagrams. The amount of information provided varies, from a simple label with the heritage name and details on its time period and creator, to multi-paragraph text. Information panels usually include information on specific heritages, though in some cases they may explain concepts or other contextual material not directly about a particular heritage. Korean and English interpretive texts are standard on most information panels (though some older information panels may not have English), and popular heritage sites also have Chinese and Japanese texts as well. Some popular sites also have brochures available in the four languages, which usually include interpretive texts, photos, and maps of the museum or heritage site. More information on the system of information panels (i.e. the various kinds of information panels, how they are situated within a heritage site) can be found in the Cultural Heritage Guide Information (Explanatory Text, Etc.) and System Improvement Plan Research Final Report (hereafter “CHA Report”) (Cultural Heritage Administration, 2014a, 3-40).

The next most widely available analog interpretive resource is speech content provided by tour guides. At popular heritages sites and at museums, guided tours are provided on a regular schedule in Korean, English, Chinese, and Japanese. However, at less popular heritage sites and museums, the languages may be limited to just Korean and English or only Korean, and may only be available with an advanced request. For large groups, heritage sites (for example Changdeokgung, Gyeongbokgung) may also recommend private, volunteer-based tour guide services such as Palace Guide or Rediscovery of Korea.[3]

Some museums or heritage sites provide performances or experiences for visitors. These events and activities are generally open to the public. Some of these performances or experiences are free while others have fees (ranging from a few thousand won to up to some ten-of-thousands of won for special performance tickets). Some must be booked in advance, like concerts or evening palace viewings, while others can be viewed or participated in without any registration. Some activities (like folk games and trying on traditional attire) and performances (especially reenactments of palace guard changes, for example) are available every day, while others (like music performances and craft activities) are available at certain times during the week (like every Saturday and Sunday) or on holidays like Chuseok, Seollal, Daeboreum, or Dano. Special events may also correspond to traditional rituals, such as the performance of Jongmyo Jeryeak once a year at Jongmyo Shrine. In addition to the events provided by museums or heritage sites are those provided by institutions which specialize in traditional performances and experiences, such as the Korea House, KOUS, and the National Gugak Center.

Libraries and museum shops--only available at some museums, Gyeongbokgung and Changdeokgung Palaces, the Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation, and some Buddhist temples--are also interpretive resources in the sense that they provide access to further interpretive resources, such as books, audio, and various cultural items, including replicas of cultural heritages.

Finally, the most in-depth interpretive resource available in person are educational and support (volunteer or financial) programs. Like libraries and museum shops, such educational programs seem to be provided only by museums or institutions such as Buddhist temples (which provide temple stays) or Confucian academies (which provide programs on the Chinese and Korean Classics - included in this are Jangseogak and Kyujanggak Archives). Educational programs can be one-time academic events, such as lectures, or more long-term classes. Some educational programs, like the Teens Workbook for Student Visits provided by Leeum Museum, are meant to be used concurrently with the museum or heritage visit, while others are separate from the heritage viewing experience. Regardless, most must be registered for in advance. In the case of the National Museum of Korea (NMK), for example, various education programs are designed for a wide variety of audiences including children, teens, adults, families, professionals, those with special needs, and non-Koreans. It should be noted that almost all education programs advertised to non-Koreans are not academic programs as much as relatively short-term experiential activities such as craft making or cooking with background information explained concurrently. Education programs for Koreans display more variety along the spectrum of experiential and purely academic. Some institutions also provide internship opportunities, such as the National Folk Museum of Korea, or volunteer opportunities, such as that provided at the NMK or the Heritage Guardians program operated by the CHA. These volunteer opportunities are advertised as being only available to Koreans (i.e. they are not included on the English-language versions of their websites). In the case of the Leeum Museum and the NMK, visitors can become “friends” or “members” of the museum by donating money, which gives them access to additional or preferential educational opportunities. The Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation also offers a thesis competition for research relating to cultural heritage education.

Digital – Offline

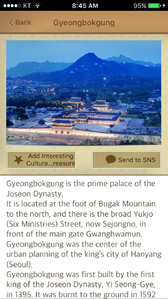

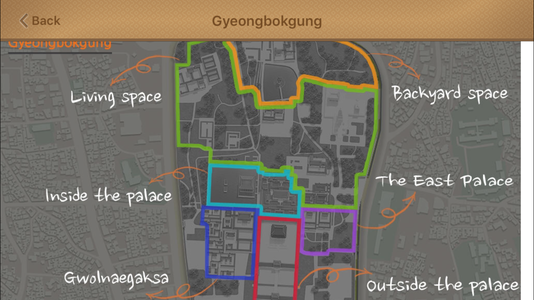

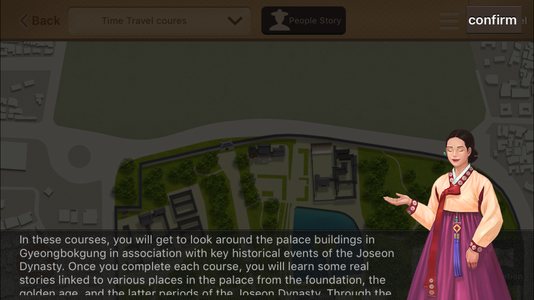

There are two kinds of digital resources: offline and online. Offline resources are those which do not need a connection to the internet to operate. This does not mean that they are not initially downloaded from the internet, but they are pre-installed or pre-downloaded in such a way that the resource can be used while not connected to the internet. Such resources can be accessed in two ways: via devices provided by the institution, such as AV guides, digital screens, or touch screen panels, or via personal devices brought by visitors, such as smart phones or tablets. Digital resources provided via institutional devices may only be accessible on-site. AV guides are usually only offered at museums and often take the place of tour guides, and allow visitors to have a semi-self-directed tour of the museum, with each heritage having a corresponding number the visitors input to hear the interpretive speech. Digital screens may provide videos or a slideshow of photos to convey a variety of interpretive content. These are usually available at museums, rather than heritage sites, although some heritages, like Jongmyo Shrine, have video to convey the various rituals or events that traditionally occur there. Some museums may have touch screens or other interactive installations which allow visitors to select additional content, including text, photos, video, and audio, about which they are interested in further learning. Some museums may also provide offline resources that are accessible via personal devices can be pre-downloaded and accessed anywhere, though they are usually meant to be used on-site in lieu of institutional AV devices. Such offline digital content available via personal devices usually comes in the form of mobile apps, though they are more like an e-book or audio guide which includes additional features such as GIS tracking, photo, video, animations, options to favorite certain heritages, and options to share information to SNS. An example of this kind of e-book style pre-downloaded mobile application is the “Palace in My Hand”[4] series provided by the CHA which is a collection of separately downloadable apps for the five royal palaces and Jongmyo Shrine.[5] The main resources (all of the photos, video, and text) of the application must be entirely pre-downloaded onto the personal device to be used (albeit in coordination with GIS location and the camera function), rather than accessed as needed as would happen with an application that connected to the internet (the CHA provides a different mobile service, “My Own Cultural Heritage Interpreter”[6] which does connect to the Internet and will be discussed below). In other words, some “mobile” resources, which one may think implies “connected to the internet,” function basically as offline AV resources which are only accessed via the visitor's personal mobile device instead of one provided by the institution directly.

- Figure 1 Screen captures from the official CHA “Gyeongbokgung, in my hands” app

Digital – Online

Online digital interpretive resources refer to resources which can be accessed via a digital device by anyone with an Internet connection. Online resources, thus, can be accessed both on-site and off-site. Such online resources usually come in the form of websites and mobile applications. Forms of online resources are varied, including searchable databases of individual heritages with photos, videos, diagrams and interpretive texts, written explanations of various concepts, glossaries of terminology with and without accompanying visual material, GIS information about heritages, or collections of narrative video content. There are so many of these resources that they are best introduced in the form of a table. These online resources have been reviewed and organized into a table by Kim (2015, 22; 40).[8][9] These websites or mobile apps all provide to the audience via the Web some kind of interpretive information about Korean cultural heritages - whether they are about specific cultural artifacts or about contextual elements (including historical figures, people, places, or events). They are organized by service type and topic. The services have been categorized into six types:

- glossary/encyclopedia – hosts a searchable list or database of terminology or entries on various items, i.e. cultural heritages

- map – allows cultural heritages to be seen on and searched for via a map, may include pre-suggested theme maps

- media content – provides academic articles or reports, photos, video, audio, 3D renderings, diagrams, etc.

- mobile app – a combination of the other service types designed to be used on a mobile device

- portal – does not directly host interpretive information, but provides searchable links to a variety of services which do

- theme – provides interpretive resources on certain topics

Not mentioned in the table are privately or collaboratively operated large-scale encyclopedia services like Doopedia or Wikipedia, which may provide quality interpretive information on cultural heritages and their contextual elements, but the scope and accuracy of which is difficult to verify. In total, the table includes 41 different digital resources (all “online” in the sense defined above except for the “In My Hands” mobile app series) by 10+ institutions on 19 different topics.

Table 10 Online Korean cultural heritage interpretive resources[10]

| Service Type | Topic | Site Name | Organization | Language | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media content | Cultural heritage | 3D Content | KCISA | Korean | 603 3D renderings of cultural heritage related items; searchable by keyword or browsable by the following categories: fashion, lifestyle item, interior design, tourism or exhibit, stationary, kitchen, education; includes rendered file and information on origin/period, material, use, owner, and a description. |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - Buddhist temple | Bulguksa Temple in my hands | CHA | Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese | In My Hands Mobile App Series; Includes basic information on sightseeing, cultural treasures, the local area, and a gallery; Includes three options for an AV guide - normal mode, time travel, and experience travel, which includes tour courses shown on an interactive map, animations, photos, audio, text, navigation, and image tracking; Includes options for posting to SNS, saving favorite cultural heritages, and making reports. |

| Glossary/encyclopedia | Cultural heritage - State and province/city designated | CHA Cultural Heritage Search | CHA | Korean | Search can be sorted by title, date, and relevance. Can only search by keyword and can only filter by designation type. |

| Portal | Cultural heritage | CHA Digital Library | CHA | Korean | Portal to the various CHA institution library pages; the main CHA library includes 62,501 materials; searchable and browsable alphabetically, by material type, and by material topic; some are available for viewing online |

| Theme | Cultural heritage - Royal palace | Changdeokgung | CHA | Korean | Theme service on Changdeokgung Palace including tourist information, information on events, educational content on history and buildings, links to related publications. |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - Royal palace | ChangDeokGung in my hands | CHA | Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese | In My Hands Mobile App Series; Includes basic information on sightseeing, cultural treasures, the local area, and a gallery; Includes three options for an AV guide - normal mode, time travel, and experience travel, which includes tour courses shown on an interactive map, animations, photos, audio, text, navigation, and image tracking; Includes options for posting to SNS, saving favorite cultural heritages, and making reports. |

| Theme | Cultural heritage - Royal palace | Changgyeonggung | CHA | Korean | Theme service on Changgyeonggung Palace including tourist information, information on events, educational content on history and buildings, links to related publications. |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - Royal palace | ChangGyeongGung in my hands | CHA | Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese | In My Hands Mobile App Series; Includes basic information on sightseeing, cultural treasures, the local area, and a gallery; Includes three options for an AV guide - normal mode, time travel, and experience travel, which includes tour courses shown on an interactive map, animations, photos, audio, text, navigation, and image tracking; Includes options for posting to SNS, saving favorite cultural heritages, and making reports. |

| Theme | Cultural heritage - For kids | Children and Youth Cultural Heritage Adminstration | CHA | Korean | Educational information on various themes relating to cultural heritage targeted at children |

| Glossary/encyclopedia | Misc. - Historical figures | Comphrehensive Information System of Korean Historical Figures | AKS | Korean | A digital encyclopedia of historical figures throughout Korean history; Some search results are hosted directly on the service while others links to entries in the Encyclopedia of Korean Culture; Can search and browse by various names (pen names, courtesy names, posthumous names, etc.); Additional glossaries of surnames and clans, government positions, civil service examinations, etc.; While the content is not directly related to cultural heritages, many cultural heritages gain their value from their relation to historical figures, and therefore, the information provided on this site serves as key contextual element information. |

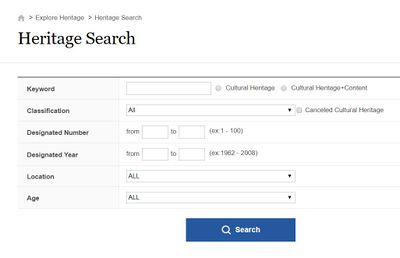

| Glossary/encyclopedia / theme | Cultural heritage - State designated | Cultural Heritage Administration English Site | CHA | English (Chinese, Japanese sites also available) | This is the English site for the CHA. It is entirely different in design and content from the main CHA site (and the Japanese and Chinese language sites which are different from the main CHA site, but the same as each other). It includes a heritage search feature for state-designated cultural heritages which bring up interpretive texts in English along with photos; The search feature includes the following filters: Location, Age (Period), and Designation Type, Number, and Year; There is basic interpretive information on the royal palaces, royal tombs, and UNESCO World Heritages. |

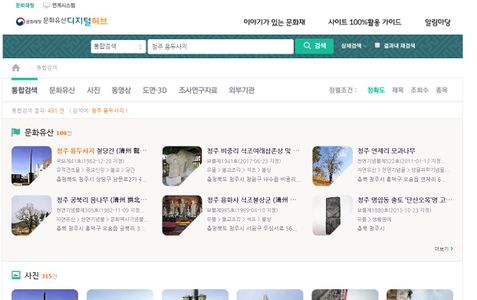

| Glossary/encyclopedia / theme | Cultural heritage - State and province/city designated | Cultural Heritage Digital Hub | CHA | Korean + | This service is mainly an improved version of the CHA Heritage Search, allowing for advanced search with filters, displaying search results for cultural heritages, photos, videos, diagrams and 3D, survey and research materials, and results from external institutions. Searches can be filtered by designation type, heritage type, region, and period and also automatically generates related heritages based on how many of these categories are shared in common. It presents the search and filter options in a more visual format. It also provides theme content, including articles and e-books, on various representative regional cultural heritages and "storytelling travel," and more. The interface is entirely in Korean, but the metadata and interpretive texts are pulled from each of the Korean, English, Japanese, and Chinese CHA websites when available; It may also be useful to note that as of publication, this service is not promoted on the CHA homepage. |

| Map service | Cultural heritage - State and province/city designated | Cultural Heritage GIS Service | CHA | Korean | Searchable map service of cultural heritages; Also includes pre-curated theme maps |

| Portal | Cultural heritage | Cultural Heritage Research Knowledge Portal | NRICH | Korean | Can search by medium, topic, or cultural heritage; Includes academic resources, 3D, diagrams, maps, video, audio, photo content on a wide range of topics relating to cultural heritages; |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - National treasures | Cultural Heritage Survey National Treasure Smart App | CHA | Korean | This app includes photo, text, and audio content on national treasures; Can be searched by keyword or browsed by heritage type. |

| Portal | Cultural heritage | Culturing | KOCCA | Korean | History and Culture Portal for Creators; Tag-based contents library of image (317,146), video (15,829), audio (13,401), and text (?) content available for reuse for educational purposes; search by content topic or type; pre-curated content including tag stories and tag tree map features; creative consulting |

| Map service | Cultural heritage - State designated | Daum Cultural Heritage Map | Daum | Korean | State-designated cultural heritages; Korean name, designation and number, period, description and photo |

| Theme | Cultural heritage - Royal palace | Deoksugung | CHA | Korean | Theme service on Deoksugung Palace including tourist information, information on events, educational content on history and buildings, links to related publications. |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - Royal palace | Deoksugung, in My Hands | CHA | Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese | In My Hands Mobile App Series; Includes basic information on sightseeing, cultural treasures, the local area, and a gallery; Includes three options for an AV guide - normal mode, time travel, and experience travel, which includes tour courses shown on an interactive map, animations, photos, audio, text, navigation, and image tracking; Includes options for posting to SNS, saving favorite cultural heritages, and making reports. |

| Glossary/encyclopedia / theme | Misc. - Local culture | Digital Local Culture Encyclopedia of Korea | AKS | Korean, English | A digital encyclopedia featuring articles and media content on a variety of topics relating to local Korean culture, among which are topics which relate to cultural heritage; includes directories (searchable by field, type, and period), indexes (on people, geographical/organization names, and books/art), a map, a timeline, and media content (including photo, video, audio, tables, graphs, and animation); Individual articles include metadata, text, media content, article author, and references, and include some links to related articles; The English version of the site is an abbrevitated version of the Korean one |

| Glossary/encyclopedia / theme | Misc. - Korean culture | Encyclopedia of Korean Culture | AKS | Korean | A digital encyclopedia featuring articles and media content on a variety of topics relating to Korean history and culture, among which are topics which relate to cultural heritage; includes directories (searchable by field, type, and period), indexes (on people, geographical/organization names, and books/art), searchable bibliography of reference materials, theme-based content, and media content (including photo, video, audio, tables, graphs, and animation); Individual articles include metadata, text, media content, article author, and references. |

| Theme | Cultural heritage - Royal palace | Gyeongbokgung | CHA | Korean | Theme service on Gyeongbokgung Palace including tourist information, information on events, educational content on history and buildings, childrens education content with quizzes, links to related publications. |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - Royal palace | Gyeongbokgung, in My Hands | CHA | Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese | In My Hands Mobile App Series; Includes basic information on sightseeing, cultural treasures, the local area, and a gallery; Includes three options for an AV guide - normal mode, time travel, and experience travel, which includes tour courses shown on an interactive map, animations, photos, audio, text, navigation, and image tracking; Includes options for posting to SNS, saving favorite cultural heritages, and making reports. |

| Glossary/encyclopedia | Cultural heritage | Heritage Terminology Dictionary | CHA | Korean | Includes 1,803 terms relating to cultural heritages in Korean and Chinese characters along with a definition of the term; can browse alphabetically or search for a particular term. |

| Glossary/encyclopedia | Cultural heritage | Heritage Type-based Search | CHA | Korean | Can retrieve a list of heritages by heritage type and sub-type (main types include historical site structure, artifact, documentary heritage, intangible heritage, natural heritage); can run a term-based search within the type-based heritage list; can download search results via Excel including designation type and number, heritage name in Korean and Chinese, region, address, manager, owner, and designation date. |

| Theme | Cultural heritage - Royal shrine | Jongmyo | CHA | Korean | Theme service on Jongmyo Shrine including tourist information, information on events, educational content on history and buildings, links to related publications. |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - Royal shrine | Jongmyo in my hands | CHA | Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese | In My Hands Mobile App Series; Includes basic information on sightseeing, cultural treasures, the local area, and a gallery; Includes three options for an AV guide - normal mode, time travel, and experience travel, which includes tour courses shown on an interactive map, animations, photos, audio, text, navigation, and image tracking; Includes options for posting to SNS, saving favorite cultural heritages, and making reports. |

| Theme | Cultural heritage - Royal palaces and Jongmyo Shrine | Joseon Royal Palace | CHA affiliate | Korean | Theme service on the royal palaces and Jongmyo Shine, including tourist information, information on events, educational content on history and buildings, links to related publications; This site does not seem to link to the individual sites for each palace and Jongmyo Shrine also featured in this table. |

| Media content | Cultural heritage | K-HERITAGE Channel | CHA | Korean, English | Videos about Korean cultural heritages; Some videos in English |

| Portal | Cultural heritage - State designated | Korea National Heritage Online | CHA | Korean | This website is divided into three sections: Learn, Explore, and Experience; The Learn Section includes video content in multiple languages, 3D renderings, e-books on heritages in each region, and educational materials; The Explore section includes pre-curated introduction and list of related or representative heritage on various topics grouped into categories such as world heritages, royal palaces and tombs, religions, history, periods, natural heritages, and people; The Experience section includes links to other interpretive resources, including those mentioned in this table like mobile apps and the Cultural Heritage Digital Hub, as well as learning and volunteer opportunities. |

| Glossary/encyclopedia / theme | Cultural heritage - Local | Local Government Tourism Sites | Local governments | Korean + | Local government sites; most have tourist information which includes information on the cultural heritages under its jurisdiction in varying degrees of depth; the amount of information in other languages varies from government to government |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - State and province/city designated | My Own Cultural Heritage Interpreter | CHA | Korean | This app is more or less a mobile version of the CHA Heritage Search website, including photos, video, metadata and interpretive texts (with auto-generated audio). Nearby heritages can be searched for, as well, using GIS locations. There is also a tab for "related cultural heritages," but through a basic test of the app, it appears that these related heritage results are not automatically generated, but pre-selected for a very few heritages like some royal palaces. The app also includes services such as a travel itinerary creator, ways to report on cultural heritages (such as mistakes on the information panels), and an SNS feature which appears to allow users make posts about their visits to heritages. Apart from the Heritage Search feature, the remaining services on the app require a personal identification log in. |

| Glossary/encyclopedia | Cultural heritage | Names of Parts of Cultural Heritages | CHA | Korean | Includes diagrams of the parts that make up heritages with the label of each part named; 44 topics/diagrams total. |

| Portal | Cultural heritage - Documentary | National Memory Heritage Service | CHA | Korean | Portal to the CHA heritage database including educational information on documentary heritage |

| Media content | Cultural heritage | National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage | NRICH | English (Chinese, Japanese sites also available) | This site's content differs to some extent from the Korean one. It includes content which relates to cultural heritages including research reports, videos, audio, slides, and the Journal of Korean archaeology. It also includes information on the various research projects relating to cultural heritages underway at the institute. |

| Glossary/encyclopedia | Cultural heritage - North Korea | North Korean Cultural Heritage Information | NRICH | Korean | A searchable list of North Korean cultural heritages which can be filtered by designation, type, material, period, and region; Includes photo material and interpretive texts. |

| Theme | Cultural heritage - Royal tombs | Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty | CHA affiliate | Korean | Theme service on the royal tombs, including tourist information, information on events, educational content on history and buildings, links to related publications. |

| Mobile app | Misc. - Tourist sites | Smart Tour Guide | KTO | Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese | This app features interpretive resources on key tourism sites (mostly cultural heritages) including text, audio, and photos; Sites are browsable via region, category, and GIS location tracking; Can also be searched for via keyword. The Korean version has more content than that in the other languages. |

| Glossary/encyclopedia | Cultural heritage | Traditional Korean Art Search | Samsung | Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese | A searchable list of cultural heritages owned by Samsung at the Leeum Museum; filterable by type; includes the name, period, material, dimensions, designation type and number, its display location, and a description. |

| Media content | Misc. - Traditional patterns | Traditional Pattern Design | KCISA | Korean | 9,718 traditional korean patterns (9,062 2D, 656 3D); information on their significance; sometimes a photo of the real heritage off of which the pattern was based; name of the pattern, pattern differentiation, origin/period, the heritage it was taken from, the owner of the heritage, the material of the heritage, explanation, design elements, items which it could be applied to, design direction. |

| Mobile app | Cultural heritage - Fortress | World Heritage Suwon Hwaseong | Gyeonggi Tourism Organization | Korean | This app includes information about Hwaseong Fortress and the Temporary Palace, with an interactive map, audio recordings of interpretive texts, links to videos, and games including true/false quizzes and spot the difference pictures. It also allows users to bookmark sites, take notes, and read QR codes. |

The list demonstrates that there already exist a significant number of resources relating to Korean cultural heritage interpretation, however, as the following sections will show, this does not necessarily speak to the quality or organization of such resources. Many of the resources have redundant information (i.e. nearly identical information on the same topic). These resources are furthermore often not linked to one another, especially inter-institutional links, which presents a challenge to the discovery of helpful and related resources.

Figure 2 Screen capture of the CHA website homepage with annotations for interpretation-related information.[11]

Figure 3 Screen capture from the “Network” pop-up on the CHA website homepage. This shows the network of main websites of the CHA, some of which do not provide interpretive resources; The Cultural Heritage Digital Hub is notably not included here.[12]

- Figure 4 Screen captures of the CHA Cultural Heritage Digital Hub website homepage and search results for Iron Flagpole at Yongdusa Temple Site.

- Figure 5 Screen capture of the Korea National Heritage Online website.

Cultural Heritage Administration Metadata

The CHA utilizes metadata in their administration of cultural heritages. This metadata can act as a kind of interpretive data, conveying interpretive information about the period, region, and type of a heritage. However, the current metadata, as shown in the figures below, is not sufficient for fully explaining the complicated context of cultural heritages. The figures and table below show three services where users can currently access metadata information about cultural heritages: the basic Heritage Search function accessible via the CHA Heritage Search, the Cultural Heritage Digital Hub, and information stored on E-Minwon site.[15]

- Figures 6, 7, 8 Screen captures of metadata for Iron Flagpole at Yongdusa Temple Site, Cheongju

Table 11 CHA Korean cultural heritage metadata[19]

| Metadata | Heritage Search | Digital Hub | E-Minwon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manager | ○ | ○ (En, Ch, Jp Only) | ○ |

| Owner | ○ | ○ (En, Ch, Jp Only) | ○ |

| Quantity/Area | ○ | ○ (En, Ch, Jp Only) | ○ |

| Period (with King) | × | ○ (En, Ch, Jp Only) | ○ |

| Name (English) | × | ○ (En Only) | ○ |

| Address | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Designation Number | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Text (Korean) | ○ | ○ | × |

| Name | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Name (Chinese) | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Text (Chinese) | × | ○ | × |

| Text (English) | × | ○ | × |

| Text (Japanese) | × | ○ | × |

| Category | ▣ | ▣ (Kr Only) | ○ |

| Designation Date | ▣ | ▣ | ○ |

| Designation Type | ▣ | ▣ | ○ |

| Period | ▣ | ▣ | ○ |

| Region | ▣ | ▣ | ○ |

| K-Heritage Channel (Video) | ○ | × | × |

| Narration | ○ | × | × |

| Photos | ○ | × | × |

| Video | ○ | × | × |

| Affiliated Items/Facilities | × | × | ○ |

| City and Province | × | × | ○ |

| Text (History, Origin, Legend) | × | × | ○ |

| Creator | × | × | ○ |

| Text (Current Status) | × | × | ○ |

| Designated Zone Area | × | × | ○ |

| Designated Zone Designated Area | × | × | ○ |

| Text (Designation Rationale) | × | × | ○ |

| Dimensions/Size | × | × | ○ |

| Form | × | × | ○ |

| Items Under Protection | × | × | ○ |

| Material | × | × | ○ |

| Misc. | × | × | ○ |

| Owner Type | × | × | ○ |

| Protection Zone Area | × | × | ○ |

| Protection Zone Designated Area | × | × | ○ |

| Structure | × | × | ○ |

It should be noted that not all heritages have an E-Minwon metadata entry, and not all metadata fields (on any of the sites) are filled out for every heritage. As the table shows, the main Heritage Search and the Digital Hub allow for filters of period, region, categorization, designation type, and designation date. However, only one of these can be selected at a time (i.e. a user cannot search for both Joseon and Goryeo at the same time; only one can be selected).

Figure 9 Screen capture of advanced search options in on the English CHA website (same as Korean advanced search)[20]

This method of describing heritages via metadata is clearly not designed with the objective of interpretation. It was originally designed for the purpose of managing heritages (see also Cultural Heritage Administration, 2014a, 247). Thus, one cannot expect it to fully describe all interpretive information. However, the CHA clearly aims to facilitate, at the minimum, searching for heritages, yet current metadata does not allow users to search for heritages in ways that may be helpful for them.

The Bridge Between Analog and Online

At a heritage site or museum, visitors usually have access to a few analog resources which could possibly connect them with digital resources: text content in the form of an information panel and sometimes a brochure, content on AV devices or mobile apps, as well as any information to further resources as advertised by tour guides. As mentioned above, AV devices are usually limited to museums, while mobile apps are also limited to the “My Own Interpreter,” “In My Hands,” and “Smart Tour Guide” apps, how well these are advertised on-site is uncertain. So, do these resources contain pathways to connect in-person visitors to digital or other analog resources? First, let us look at the information panels. All newly installed information panels have a QR code which links to the online version of the interpretive text as provided via the Cultural Heritage Administration site. The link opens in a browser, which is almost identical the “My Own Interpreter” mobile application interface. The mobile link includes photos (as well as video and documentaries for some more well-known heritages), an option to have the interpretive text play as audio, as well as interpretive texts in English, Japanese, and Chinese when available (usually for state-designated heritages only). In some cases, like Baekje Historic Areas, the QR codes may link to interpretive texts and photos provided on the website of the institution which manages the heritage.[21]

Figure 10 On-site information panel with QR code[22]

The on-site interpretive texts and online interpretive texts usually differ. The online interpretive texts are generally slightly longer, with most of the information largely the same, just written in a different order. Therefore, whether they provide any greater detail than the on-site text varies entirely from heritage to heritage. Metadata on the heritage is provided, but in Korean only.[23] There is also a tab for “Related Heritages,” but these appear to be only available for the royal palaces and Jongmyo Shrine.[24] The only external links available on the page are to the CHA mobile homepage, a search bar, Facebook, and Twitter. The mobile search function only allows for keyword based searching and does not allow for any filtering based on metadata (such as a period, location, or heritage type), nor does it allow for results to be sorted alphabetically.[25] If the visitor clicks on the link to the CHA mobile homepage, they are taken to a mobile version of the CHA homepage, which does not include any links to the terminology or diagram glossaries as provided on the desktop version of the site.

Based on this, what options does the visitor have to seek out further resources based on the information panel? The online content as accessible via the QR code does not include any links to definitions or explanations of any related people, places, events, or concepts that the visitor may have been curious about or not fully understood. There is also no way to find similar or nearby heritages.[26] The one action which is facilitated is to follow the CHA via Facebook and Twitter and check the CHA homepage. Furthermore, the mobile version of the CHA homepage does not include information about any education or volunteer opportunities, and while an event list is provided, these events are not related to the heritage the visitor is visiting.

Let us next consider the brochures. Not every heritage site has a brochure or pamphlet. Sometimes the only additional resource is a local tourist guide with maps and information about local heritage sites (including the one the visitor is currently visiting), cultural events, and restaurants and local goods. To gauge the extent to which brochures (among those brochures that are available) inform visitors about further resources, 25 brochures from major museums and various heritage sites were collected and reviewed.[27] They included 11 individual heritage sites, 10 museums, and four local tourist guides. All include admission information or directions and short interpretive texts of the various heritages available to see, usually with accompanying photos. Almost all brochures contain a website link or QR code linking to a website. Many include maps which show nearby attractions, including other heritages. Only three mentioned SNS resources, and these were all museums. Only five museums, all four local tourist guides, and one individual heritage site included information on further educational or experiential opportunities. Only two local tourist guides made mention of a mobile app (one of which no longer seems to be available), and none of the brochures mentioned anything about the mobile apps provided by the CHA or the Smart Tour Guide. This shows that the main role of brochures seems to be duplicating the interpretive information on the information panels and providing admission information, rather than advertising to visitors further interpretive resources (analog or digital) - apart from some museums and local tourist guides. In the other direction, digital resources seem to provide significant information on analog resources, including information on events, educational programs, heritage admission information, etc. They also sometimes link to other digital resources; however, it is rarely made clear exactly what content is on those digital resources; audiences have to click the link and open the site to find out. Oftentimes, websites which should be advertised on one another are not. For example, the main Royal Palaces website and the individual palace and shrine websites, are not linked to one another, even though they are made by the same organization and are obviously related, while the Digital Hub website is not advertised anywhere on the CHA Homepage, and seems to be advertised only via the Korean National Heritage Online website. Digital resources provided by other institutions (even if they are a part of the same Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism) are also rarely featured on one another. Therefore, this may cause confusion as to what resources exist online, what content is provided on each website, and how to access those websites.

Processes

The purpose of this section is to explain how, by whom, and based on what standards interpretive resources are composed and translated. As shown in the previous section on interpretive resources, such resources are developed and provided by a variety of institutions. However, it is difficult to ascertain the exact processes of resource development and translation for all institutions – partly because there are so many, but also because there is no public information or official guidelines on how and by whom such resources are developed. Furthermore, it is not necessary to understand how all resources are developed to gain an understanding of the general practices. Therefore, this section focuses on the composition and translation of interpretive texts found on information panels at heritage sites (and online). Such texts are available for almost all heritages and are, as such, the most widely available and utilized interpretive resource. This section focuses primarily on the methods employed by local governments, which are responsible for most interpretive text composition and translation.

There is no official process outlined by the Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA) for the composition and translation of Korean cultural heritage interpretive texts. When possible, official guidelines and documents provided by the CHA regarding interpretive text composition and translation have been referred to (Cultural Heritage Administration 2010, Cultural Heritage Administration 2014a). An official at the CHA in charge of information panels and a member of the exhibit department of the National Museum of Korea were contacted via phone in an attempt to understand who is in charge of the interpretive text composition and translation process, however neither could say exactly who was in charge of interpretive text composition nor what their qualifications were. Due to the fact that it is nearly impossible to find official information on the composition and translation process of interpretive texts by any other means, much of the accounts in this section are written from the researcher's, and her colleagues', personal experience editing and translating interpretive texts as a part of the Korean Cultural Heritage English Interpretive Text Compilation Research Team (hereafter Research Team)[28], which has fact-checked and translated over 130 interpretive texts on behalf of ten local governments across the country, as well as directly for the CHA, over the course of nearly two years, and whose members have had years of experience beyond this in the field of cultural heritage-related translation work. The fact that it cannot be known exactly how, by whom, and to what standard interpretive texts are composed and translated, demonstrates the shortcomings of the current process, as will be evaluated later in the thesis. Thus, this section should be seen as an overview of how the composition and translation of interpretive texts has been undertaken at various times in the recent past, but may not apply to all scenarios.

Although cultural heritages are registered with the CHA, the composition and translation of the majority of new or updated interpretive texts are under the jurisdiction of the institutions which directly own or manage cultural heritages. Included among these institutions are, of course, public and private museums and archives, historical sites such as palace complexes and UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and private collections. But, also included are local province, city, county and district governments (of which there are 250 total) which oversee most on-site heritages such as historic houses, Buddhist temples, Confucian academies, commemorative pavilions, tombs and shrines, natural monuments, fortresses, and the objects contained there within. While there are guidelines regarding the content and design of interpretive texts and information panels provided by the CHA (2010, 2014a), there are no official regulations regarding qualifications of the authors or translators, or what process should be followed. Therefore, each institution is at liberty to compose and translate interpretive texts as they wish, resulting in differences in the order of the process and the kinds of individuals or organizations to which work is outsourced.

Museums, archives, palace complexes and UNESCO sites often have staff who are professionally trained in museum or archival studies, and thus have some level of knowledge the composition of interpretive texts as well as cultural heritages themselves and may be able to do some interpretations in-house. However, local governments are staffed only by civil officials who likely have no knowledge of cultural heritages or interpretive composition, let alone translation, staying in their position for a short period of a few years or less. Therefore, the composition and translation of interpretive texts must be outsourced. However, it is up to the jurisdiction of each local government to whom to outsource these jobs, and each local government may have different financial resources and human connections with which to work. There have been multiple cases (in the experience of the Research Team) in which the civil official in charge of overseeing the composition and interpretation process is brand new to their job and had been provided with almost no information about how to go about it.

How the Korean interpretive texts are composed varies. In the case of newly registered heritages, the texts are usually based off the reports which detail the reasons for a heritage receiving its designation, which are usually compiled by or approved by academics (as will be shown in the evaluative section, however, this information is not always accurate). However, who actually composes the interpretive text – its structure, whether terminology is explained or not, etc. – is unclear. In cases when a new information panel is being installed for an existing heritage, the same Korean text may be reused, or it may be altered in some way. Sometimes these texts are (nearly) the same as those provided on the CHA website (the authors of which are also unknown), other times they are different. Sometimes there is additional information added, but where such information is sourced from is unknown. Furthermore, though ideally the guidelines and suggestions made in the Cultural Heritage Information Panel Guideline and Improvement Case Studies (Cultural Heritage Administration 2010) or Report (Cultural Heritage Administration 2014a) are followed regarding content and stylistic choices, this seems to be more often than not, not the case, and who is responsible for making those editorial choices, and their qualifications to do so, are unknown. As a result, the structure, tone, and content of the Korean texts vary widely.

English translations are based on the original Korean texts, but there are almost no guidelines for the English translations (as is shown in the following section). How translators are recruited is also unknown. Even the Research Team does not know exactly by what means local civil officials get its contact information.[29] Oftentimes, the responsibility of text translation is passed on to the design company responsible for designing the information panels, and there is no way to know how they are finding translators or what those translators' qualifications are. After translations are made, they may or may not be proofread by Koreans and/or native English speakers. In cases when previous translations are found to be of extremely poor quality, they may be retranslated by different translators. After compositions and translations are finalized, they are sent to a design company, after which they are double-checked for errors in the layout process, and then made into information panels.

Very little is known about outsourced authors, translators, and fact-checkers and editors of interpretive texts. Surely some payment records may exist which show to whom the work was outsourced, however as this information is not made public, and because civil officials change so frequently, this information is quickly forgotten. When the outsourcing of translation is given to the information panel design companies, even local governments may have no record of who translated the texts. As a result, we cannot know what these authors', etc., qualifications are, how they were recruited, or what information (such as guidelines) they were provided regarding how to compose or translate the interpretive texts. This also means that new civil officials tasked with the job of getting new interpretive texts made may have difficulty finding reputable interpretive text authors and translators. Furthermore, due to a lack of cultural heritage expertise and interpretive text composition skills, along with limited time and budget, local civil officials in charge of interpretive text composition and translation may have little option but to approve the texts and their translations without fact-checking or proofreading by other experts, cultural heritage educators, or native English speakers.

The interpretive texts also do not undergo any approval process with the CHA, and neither are they sent to the CHA for further use or upload on the CHA website. The only time the CHA would be contacted about the content of the interpretive texts is if there is some specific problem discovered regarding factual information which needs to be reviewed by an expert – in which case a member of the CHA's advisory committee would be contacted. As mentioned above, the CHA does provide composition, translation, and design guidelines (2010; 2014a), it cannot be known whether these guidelines are actually provided to authors or translators, or if they are, to what extent they actually followed without surveying all organizations and individuals involved with interpretive text composition and translation, a large undertaking not within in the scope of this thesis. As will be showed in the following sections, many interpretive texts include terminology which is difficult for ordinary Koreans to understand and the content and style of the writing varies widely even among otherwise similar heritages. And, regarding English translations, it is clear that in many cases (especially outside of Seoul) interpretive texts are not proofread by a native speaker even for basic grammar and punctuation. To those who know a bit about cultural heritages, it is also clear that the translators usually do not have any background knowledge of Korean cultural heritages. This all suggests that guidelines regarding interpretive texts and their translations are not being followed, that not all authors and translators are qualified for the job, and that the texts and translations are not edited after being received by civil officials. In other words, there is, in practice, little oversight of the content and translations of interpretive texts by local governments, and no oversight by the CHA.

In summary, based on information available on the CHA website and inquiries of the CHA and local governments, what can be known for sure is that there is no one person or division responsible for overseeing interpretive texts, including their composition, translation, presentation, and utilization. There is no standard system for creating and translating interpretive texts. The composition and translation of interpretive texts is the solely the responsibility of civil official-staffed local governments. Any fact-checking or proofreading is managed either locally or via inquiries of the advisory committee at the CHA. The installation of on-site information panels, the development of educational content, and the development and management of the CHA online search engine and apps are managed by entirely different divisions of the CHA. In the case of independent sub-organizations (such as the palaces in Seoul, museums, and archives), the management of websites and the interpretive content provided there within appears to be entirely separate from the CHA divisions mentioned above. Thus, we can see that the composition and translation of interpretive texts is not only divided by locale and discipline, but is considered as work which is entirely separate from the development of educational or digital content at the CHA.

On-Site Interpretive Text Guidelines

In 2010, the CHA provided guidelines for information panels, which focused mostly on the design standards for the panels, but also included a section on interpretive text composition and translation (Cultural Heritage Administration 2010). This guideline is the only official guideline provided by the CHA. It is as follows.

Content should include (39):

- history and origin of the heritage

- its historical and cultural value

- related myths, legends, and folk beliefs

- key visitor points of interest

- other things the author deems appropriate

Guidelines for English translations:

- partial translation of the original text

General Guideline Principles (41):

- The objective of the central information in the informative text is to convey objective facts. However, if it serves to convey some sympathy or allow the visitor to experience greater interest in the heritage, content which may be considered subjective information may be added.

- Historical facts should be based on that which is officially approved; the Cultural Heritage General Survey and reissued content on CHA homepage should be considered first.

- The language and content should be easy and simple so that visitor may discern the respective cultural heritage. If necessary a drawing or photo can be included, is should be in accordance with the design and layout of the informative panel.

- Sentence order can vary depending on the importance of the content, with high priority content being written in the first sentence; Apart from special circumstances, this determination of importance is left up to the author.

- The first sentence should be written to include information to discern the respective heritage, with the heritage's function, origin, unique qualities, and historical and cultural value coming first.

- Depending on the form, size, or scale of the panel, content may be omitted or minimized. (Example included)

- If there are related myths or legends, these should be actively utilized; Even if they are just contemporary facts or a story, they should be included if they provide visitors with fun, emotion, or valuable information.

- When possible, expert terminology or abstruse language should be avoided within the informative text; if inclusion is absolutely necessary, then an explanation of the term should accompany it. (Example included)

- The English translation should be an interpretation, not a direct translation, of the original text; When needed, additional text can be added solely for the English text.

- Any sentence which does not relate to the explanation of the cultural heritage should be omitted.

The guideline also states that heritages have artistic, historical, and academic value and provides the following tips for how to convey such values:

- Depiction of artistic value: “should strive for a balance between depicting both the heritage's universal and individual beauty, should have additional explanations of why it is beautiful, and should explain the heritage's beauty in such a way to avoid too much comparison to other heritages (40).”

- Depiction of historical value: “should focus on explaining the historical events of key figures. Explanations should focus on the facts, but should strive to make the reader feel like they are brought into the historical time and space [of the key figures and events] (48).”

- Depiction of academic value: “contains inherent difficulty in that they must use terminology to convey the expert and academic value. They should explain the unique and contrasting features of the heritage by explaining the various elements which make it up, and if necessary, should convey a time-space perspective by showing convenience or change as created by a particular construction method or technique (59).”

The guideline also includes formatting rules for dates, Chinese characters, and dimensions, but does not take into account how these may need to be formatted differently in English.

The content as prescribed in the guideline is vague in nature. It fails to discriminate in the content that should be included for heritages of different forms - for instance, the content included in an interpretive text for a painting would be much different than that of an interpretive text for a historical site, yet the guidelines do not differentiate these different forms. It also does not clearly outline the order of the content, merely stating that the “most important” information, including “function, origin, unique qualities, and historical and cultural value” should be in the first sentences. Furthermore, the guideline provides few best practice examples for the author or translator to model, failing to show examples of a well-structured text, how to responsibly include subjective stories such as myths, or what is “too much” comparison with other heritages, or how one might “bring the reader into the historical time and space” as referenced in the tips. The guidelines for translators to “partially translate of the original text” and avoid a “direct interpretation” may not be helpful for translators in their judgment of what content is suitable for foreign audiences, i.e. specifically what kind of information should be omitted and included. There is also no mention of making sure common terms and their definitions are consistent across interpretive texts.

By leaving the content, structure, and style up to the author and translator, the CHA also assumes that the authors and translators know best what is most important, what the audience ought to know, and how it should be conveyed. Yet, as was explained above, the identities of said authors/translators and their qualification to judge what audiences “ought to” know are unknown. Furthermore, the guideline implies that the interpretive text will only be conveyed in text (as opposed to visual) and print (as opposed to online) forms – despite the fact that the interpretive texts are often provided online. Apart from suggesting the inclusion of a complex map in the case of a site with multiple structures, it does not ask the author to consider alternatives ways to convey the interpretive information in a timeline, chart or diagram. It also does not mention the inclusion of links to related media, further reading, or definitions of terms or historical figures – all of which are very easy to include in online interpretive texts and could significantly aid in the reader's comprehension of the information.

To supplement the 2010 guidelines, the CHA published a report in 2014 (Cultural Heritage Administration 2014a) which detailed the extent of problems with the English translation of the interpretive texts, and suggestions for the structure a digital information system while also providing additional composition guidelines and suggested improvements for both Korean and English interpretive texts based on international standards and case studies of interpretive texts at heritages abroad (147-239). This report was completed by the Cultural Informatics Lab at the Academy of Korean Studies on behalf of the CHA. The report first includes a Korean translation of the ICOMOS standard for interpretation and presentation (147-151). It then looks at case studies of interpretive texts abroad, from countries including six from England, two from Japan, and two from China (152-166).

The description of what content should be included in the interpretive text (167-170) is the same as the 2010 guideline, except that it also includes “human interest story; interesting storytelling elements related to the heritage such as facts, people, events, etc.” and created a category for additional information (to be included in brochures, online) in which myths, legends, and folk belief as well as the origin and history of related people, events, are included. For English interpretive texts, it suggests omitting or supplementing information in consideration of the foreign audience, creating an objective depiction that considers East Asia and the entire world, and including spatial or temporal comparison if necessary. It also outlines questions and elements which should be answered via the interpretive text, such as:

- What is it?

- What origin or story does it have?

- What value or excellence does it have?

- An explanation of how to view/appreciate it

- Administrative information (i.e. dates and places of creation, relocation, restoration, designation) should be shown separately

The report goes on to outline further rules and standards for composition of both Korean and English interpretive texts.

Korean interpretive text principles (170-3):

- An interpretive text with the general public as the target audience

- Contextualized depiction

- Organic explanation

- A cultural heritage that is meaningful for today

- Utilization of storytelling techniques

- Exclude description of shape/form

- Sources with facts that are officially approved by academia

Korean interpretive text standard in detail (173-4):

- Easy terminology, easy sentences

- Key value and unique features in the first part

- Short text, separated sentences

- Proper grammar, strong sentences

- Formatting that matches official standards

English interpretive text composition principles (174-6):

- The majority of foreigners do not have background knowledge on Korea.

- The mere translation of a Korean interpretive text does not beget an English interpretive text.

- Does not make abstract or exaggerated assertions or explanations.

- Interpret with a context that connects with elements both in Korea and abroad.

- Information panels are read by diverse people.

- Simple language is an international trend.

English interpretive text standard in detail (176-7):

- Easy terminology, easy sentences

- Key value and unique features in the first part

- English-like and concise sentences

- Formatting that matches official standards

The report then goes into specifics about the proper style formatting for English interpretive texts (177-199).

Based on these guidelines, the report analyzes 19 sample interpretive texts in both Korean and English, outlines their specific failures based on the guidelines, and recomposes six Korean texts and five English texts to meet the guideline and serve as best practice examples (200-239). The samples include palace/shrine complexes and buildings, Buddhist temple complex, statue, painting, and stele, a royal tomb, a battlefield, a magistrate's office, a traditional house, a Confucian academy, a fortress, two folk villages, a natural monument (tree), a scenic site, and two dolmens.

This report successfully addresses some of the weaknesses of the 2010 report, namely how to compose interpretive texts in a way that considers the general public's background knowledge and interests. It also provides numerous, specific examples to help the author/translator understand exactly what is meant by the recommendations, while also adding a section for English formatting. Yet, this report falls short in outlining interpretive text content in detail (with distinctions for different kinds of heritages which would naturally include different information), specifying exactly what kinds of omissions or supplements need to made for English interpretive texts, addressing how to overcome the inherent bias of having a text written and translated by a single author/translator, and considering non-text, non-print forms of interpretation.

While the 2014 report is a significant improvement on this front, neither report provides specific guidelines on how to translate certain commonly occurring cultural heritage terminology, nor do they specify exactly when to omit or supplement information for foreign audiences. There are also various resources for translators, including online and print glossaries, dictionaries, and books in English relating to Korean cultural heritages. One CHA resource available is the 2014 English Names for Korean Cultural Heritages (Cultural Heritage Administration 2014b), which lists officially sanctioned translations for terms appearing in the names of Korean cultural heritages, as well as the English names for all nationally designated and registered cultural heritages. Translators may also reference previously composed interpretive texts available online. However, these resources significantly vary in quality and it would be difficult for the average translator, especially a non-native English speaker and non-expert on cultural heritage, to judge. Most importantly, these resources are not provided to translators by local governments or the CHA, and it would be up to the translator to seek out and/or purchase such resources themselves. Given that many current interpretive text translations do not even follow basic Romanization standards, it is unlikely that the vast majority of interpretive text translators ever referenced such resources.

In summary, both guidelines fail to acknowledge the bias and weaknesses of authors and translators, while also not considering digital applications of the interpretive resources. They also lack specificity in terms of content and fail to provided translators with sufficient resources for translating cultural heritage terminology. However, even if these were sufficient guidelines for authors and translators to work with, there is no way to know whether authors or translators were ever provided with such guidelines or resources prior to doing their work. Since it is up to each local government to outsource the work, if they fail to convey these guidelines, then the guidelines lose their meaning. And even if they are provided, it is uncertain if the author or translator will follow them. Given that the CHA does not request, let alone approve, these interpretive texts, the local government has no incentive to make sure the guidelines are followed.

Content

Before we can understand how we may reimagine interpretive content in a way which maximizes utilization of the full range of digital technologies – as will be discussed later – we first must clearly understand what interpretive content includes. This is necessary prior to undertaking the design of an ontology which will serve as the framework for future applications of interpretive content. The most accessible form of interpretive content is the interpretive text, as can be accessed online, can be easily reorganized and sorted through, and does not vary the way oral presentations may. The reason the content which makes up existing interpretive texts must be reviewed is that there must be a clear and precise understanding of the various elements which make it up and the ways those elements relate to one another. However, interpretive texts, as was argued in previous sections, are not complete, nor are they always successful in achieving their interpretive objectives. In this process of analyzing the interpretive texts to understand the nature of their content, both information which is unhelpful and unnecessary, as well as information which would be useful but is missing, can be identified. This also allows for gaps in previous guidelines to be filled in.

The Korean Cultural Heritage English Interpretive Text Compilation Research Team (hereafter Research Team) has reviewed the content of and developed a standard structure for interpretive texts through its translation of over 130 interpretive texts. The original Korean texts often had illogical and inconsistent organization of information, with seemingly unimportant facts being presented first, and important key points presented last. These inconsistencies are not intentional reflections of the varied values and natures of the heritages, but rather merely a consequence of a lack of oversight. If translated into English with the same structure, foreign audiences would have a hard time understanding the significance of the heritage. Therefore, the Research Team sought a standard for how to organize and structure the information in English translations which would be more effective in achieving interpretive objectives. In other words, rather than simply retranslating the sentences as found in the Korean text, the team wanted to parse out the key points the interpretive text was attempting to convey, and use these points to compose an entirely different English text in a structure that was methodological and clear. Therefore, the key kinds of information found in the original texts were broken down and organized into a standardized structure. This analysis was not necessarily done in a scientific or methodological way from the start, but was a result of trial-and-error in the process of retranslating over a hundred interpretive texts. The following guideline is based on that original structure developed by the Research Team, but more detail has been included by the author.

- Definition

- What kind of heritage is it?

- How old is it or its legacy (date or period)?

- What or who does it depict or commemorate? (if applicable)

- What was it used for? (if applicable)

- What kind of value does it have? For example:

- first of its kind

- oldest extant of its kind

- well-preserved in its original condition

- representative of a time period or form

- has unique features that different in a meaningful way from similar heritages

- provides academically valuable information

- related/dates back to an important historical figure, event, site, or object

- Related People, Events, Sites, and Objects (if applicable)

- Definition of the person, event, site or object

- What is the relationship between the heritage and the person, event, site or object

- What is the significance of the person, event, site or object

- Description

- Where is it held?

- Of what is it comprised?

- materials

- parts

- What qualities do those parts have?

- What do those parts and qualities have to do with its value? (if applicable)

- History

- How has it physically changed over time? For example:

- repaired/renovated

- rebuilt

- relocated

- parts lost/added

- expanded in size

- destroyed

- discovered/excavated

- How has its functionally changed over time? For example:

- change in uses

- renamed

- changed owners

- Who or what was responsible for the above changes?

- How has it physically changed over time? For example:

- Dimensions

- height, width, depth, weight

- Korean units (i.e. kan)