(Translation) 擊蒙要訣

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | Key to Breaking Folly's Hold | |

| Chinese | 擊蒙要訣 | |

| Korean(RR) | 격몽요결 (RR: Gyeogmongyogyeol, MR: Kyŏngmong yogyŏl) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Literati Writings | |

| Type | Children's Primer | |

| Author(s) | 李珥(1536-1584) | |

| Year | 1577 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | 革舊習, 持身 | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2017 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Intermediate Training Group) | |

| Editor(s) | Sanghoon Na | |

| Year | 2017 | |

Introduction

This is an English translation of Yi I's Gyeongmong yogyeol, but contains only two parts of the book, which are the second chapter and the third chapter(Author's preface and the first chapter were already submitted to the Review of Korean Studies). There already appeared a complete English translation[1] for general readers in 2012, which is also uploaded on the website.[2] The published version, however, presents no more than a literal translation without a primary text or an annotation. So here this one attempts to offer a new version which is more faithful to the primary source text and supplies a proper amount of footnotes that the reader can find useful.

Yi I 李珥 (1536-1584) was one of the most prominent Confucian scholars during the Joseon period. He was also an active politician but left office in 1576 because of the factional strife between the Easterners and the Westerners.[3] The place where he went was his wife's hometown, Haeju in Hwanghae province (now located in North Korea).[4]

While he was in Haeju, a few students came to see him to ask questions about learning. At first he was reluctant to answer them because he had two problems. One belonged to himself, and the other to the students. He considered himself to be unqualified to teach and deemed them ineligible to learn unless they had a strong will. He wanted to give them something more than a makeshift solution or a desultory talk about learning.

In order to solve those two problems, he wrote Gyeongmong yogyeol 擊蒙要訣 (Key to Breaking Folly's Hold[5] in 1577.[6] By doing so, he did not have to teach them in person on the one hand, and he could provide them with something substantial, meaningful, and serious about learning.

There were two results he expected to get from himself and his readers. He wanted to alert himself with his book along with the Jagyeongmun 自警文 (Written to Alert Myself).[7] And furthermore, by his writing, he was eager to see the students' minds being cleansed and their decisions to learn being firmly made, and their actions being performed on the very day.

Besides the author's preface, the book consists of ten chapters that are unfolded as follows: making a resolution 立志, revamping the old habits 革舊習, conducting oneself 持身, reading books 讀書, serving parents 事親, performing mourning rites 喪制, conducting ancestral rituals 祭禮, staying at home 居家, treating others 接人, and finally, living in society 處世 in the last chapter.

Preface and Chapter one

Click on the following link "Preface and Chapter one"

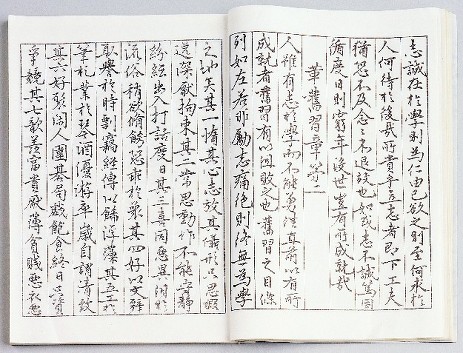

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

革舊習章 第二 02-01 人雖有志於學 而不能勇往直前 以有所成就者 舊習 有以沮敗之也 舊習之目 條列如左 若非勵志痛絶 則終無爲學之地矣

持身章 第三 03-01 學者必誠心向道 不以世俗雜事 亂其志然後 爲學有基址 故 夫子曰 主忠信 朱子釋之曰 人不忠信 事皆無實 爲惡則易 爲善則難 故 必以是爲主焉 必以忠信爲主而勇下工夫然後 能有所成就 黃勉齋所謂眞實心地 刻苦工夫兩言 盡之矣

|

革舊習章 第二 Chapter 2. Revamping the Old Habits

The reason why one is not able to courageously proceed straight ahead to [his] achievements, although he sets his mind on learning, is that his old habits prevent and discourage his mind. A list enumerates these old habits below. Unless one exerts his mind and ruthlessly breaks these habits, then in the end, there will be no base of learning.

The first habit is laziness of one's mind, a loose demeanor, thinking only of being free and idle, and deeply hating to be constrained, or disciplined. The second is constantly thinking of moving, not able to preserve the quietness, confusedly coming and going, and spending the day talking. The third is like to be same [as everyone else] but hate to be different, being familiarized with current customs, and only a little want to cultivate oneself and be cautious, being afraid of being alienated from majority. The fourth is to prefer to gain fame by literary skills in the generation, and decorate flowery writings by plagiarizing the classics. The fifth is to put efforts in [fancy] composition, be indulged in music and wine, and waste a year flirting and playing, talking to oneself that these are refined tastes. The sixth is to like gather idlers, play paduk(go) or chess, spend a day glutting oneself with foods, and only try fighting and competing. The seventh is to wish for riches and honor, but hate poverty and lowliness, being deeply ashamed of bad clothes and bad food.[8] The eighth is to enjoy carnal desires without self-control, being unable to cut them off, and consider property, wealth, music, and women as sweets.

Those harmful to mind among habits are generally like these. The others are hard to enumerate in detail. These habits make people's resolution week and make their conduct insincere. What one has done today is hard to correct tomorrow. In the morning one regrets his misconduct but in the evening he is supposed to do so again. One must greatly stir the brave heart, as if he sharply cut off tree roots with a stretch of the sword, and cleanse his heart so that not the slightest stain would be left and always exert the effort of rigorous self-examination. Only after ridding this mind of old contamination without a single spot, one would be able to consider the study of the advancement to learning.

03-01 學者必誠心向道 不以世俗雜事 亂其志然後 爲學有基址 故 夫子曰 主忠信 朱子釋之曰 人不忠信 事皆無實 爲惡則易 爲善則難 故 必以是爲主焉 必以忠信爲主而勇下工夫然後 能有所成就 黃勉齋所謂眞實心地 刻苦工夫兩言 盡之矣 A learner must face towards the Way with sincere heart and not disturb his will with various worldly matters, and then the pursuit of learning may have the foundation. Therefore, the Master said, "Hold faithfulness and sincerity as first principles."[9]. Master Zhu interpreted it and said, "One who is not loyal and trustworthy is all of his work is not truthful. Doing evil is easy, while doing good is hard. Therefore, one must take these to be of primary importance." Only after holding faithfulness and sincerity as first principles and resolutely set about studying, one would be able to have something accomplished. Huang Mianzhai[10] said, "Make your heart truthful. Be assiduous in your studies." These two sayings exhaust the meaning of what Confucius said.

Always one must rise early and retire late and properly order his clothing and cap. One's facial expression must be solemn and kneel down with his hands joined across his breast, and walk leisurely and carefully. Be cautious in your speech. Do not take each movement and repose lightly and let them go carelessly.

03-03 收斂身心 莫切於九容 進學益智 莫切於九思 所謂九容者 足容重(不輕擧也 若趨于尊長之前則不可拘此) 手容恭(手無慢弛 無事則當端拱 不妄動) 目容端(定其眼睫 視瞻當正 不可流眄邪睇) 口容止(非言語飮食之時則口常不動) 聲容靜(當整攝形氣 不可出噦咳等雜聲) 頭容直(當正頭直身 不可傾回偏倚) 氣容肅(當調和鼻息 不可使有聲氣) 立容德(中立不倚 儼然有德之氣像) 色容莊(顔色整齊 無怠慢之氣) 所謂九思者 視思明(視無所蔽則明無不見) 聽思聰(聽無所壅則聰無不聞) 色思溫(容色和舒 無忿厲之氣) 貌思恭(一身儀形 無不端莊) 言思忠(一言之發 無不忠信) 事思敬(一事之作 無不敬愼) 疑思問(有疑于心 必就先覺審問 不知不措) 忿思難(有忿必懲 以理自勝) 見得思義(臨財必明義利之辨 合義然後取之) 常以九容九思 存於心而檢其身 不可頃刻放捨 且書諸座隅 時時寓目 In possessing one's mind and body in a condition of recollection, nothing is better than the Nine Looks. In advancing to the learning and increasing knowledge, nothing is better than Nine Considerations. The so-called Nine Looks are as follows: [11] Feet should look grave. (Do not move your feet lightly. If you have to walk fast before elders[12], then you are not obliged to this [rule].) Hands should look polite. (Hands should not be sluggish. When there is no work at hand, then you must fold hands together and do not move them rashly. Eyes should look straightforward. (Fix your eyes and eyelashes. In looking down or up should be right. Do not ogle or look askance. Mouth should look closed. (If it is not time to speak or eat, then mouth should not be opened all the time.) Voice should sound quiet. (Properly arrange and conserve your material force. Do not make sundry sounds like belching, cough, and so on.) Head should look upright. (Adjust your head properly and straighten your body. Do not turn askew with your head tilted.) Breathing should look solemn. (Adjust the nose breath. Do not make a breathing sound. Standing should look virtuous. (Stand straight without leaning. Sternly have the spirit of virtue.) Face should look serious. (Countenance should be well-ordered without expression of negligence.) The so-called Nine Awarenesses are as follows:[13] In seeing, be aware of clarity. (In seeing, if there is nothing to block the sight, then it would be bright and there would be nothing invisible.) In listening, be aware of acuity. (In listening, if there is nothing to obstruct the hearing, then it would be clear and there would be nothing inaudible.) In countenances, be aware of warmth. (Face should be mild without the expression of anger.) In attitude, be aware of courtesy. (In body and demeanor there should be nothing untidy or frivolous.) In speech, be aware of truthfulness. (Even in uttering a word there should be nothing untruthful or untrustworthy.) In work, be aware of reverence. (Even in doing a [small] work there should be nothing disrespectful or incautious.) In doubt, be aware of question. (If you have doubt in your heart, go to a precursor and accurately inquire. If there is something unknown, do not leave it.) When angry, be aware of the difficulties that may ensue. (If you have an anger, restrain it. Overcome yourself with principle.) When seeing gain, be aware of righteousness. (Facing wealth, clarify the division of righteousness and profit. Only after it becomes harmonious to righteousness, take it.) Always keep the Nine Looks and the Nine Awarenesses in mind and examine yourself. Do not neglect [them] even for a second. And write them on the corner of the seating place. Set eyes on them all the time.

If it is not [in accordance with] propriety, do not look. If it is not propriety, do not listen. If it is not propriety, do not speak. If it is not propriety, do not act.[14] These four [injunctions] are the essentials of self-cultivation. Whether it is propriety or impropriety, it is difficult for a beginning student to discern, so that it is necessary to exhaustively investigate principle and clarify it. If only he diligently practice what he already knew, then his thoughts will embrace more than half [of the knowledge].

The pursuit of learning lies in the matters of everyday life. If, living in daily life, one is respectful when dwelling at home, mindful when handling affairs, and loyal in relationships with others be loyal,[15] then this would be called "the pursuit of learning." The act of reading a book is no other than to trying to clarify this principle.

Clothes should not be luxurious but no more than keep out the cold. Food should not be sweet and tasty but no more than stave off hunger. The dwelling place should not be too comfortable but no more than avoid being sick. As for the effort for learning, the right way for inner training, and the norms of decorum and dignity, one should work hard daily but not be self-complacent.

The study to overcome oneself is the most urgent in daily life. The so-called self is that what my heart desires is not in accordance with Heavenly principle. It is essential to examine my heart to see if it desires beauty, profit, fame, government position, rest and ease, the pleasures of feasting, or valuable curios. If all things being desired are not in accordance with the principle, then cut them all sharply and do not leave any buds or veins. Only after that, what my heart desires will begin to be in the righteous principle and there will be nothing to overwhelm myself.

Much speech and many worries are the most harmful to inner training. If there is no work, then sit in silence and preserve your heart. When meeting others, make choice of words and deliver them succinctly and cautiously. If one speaks timely, then words cannot but be succinct. Those who speak succinctly are near the Way.

If not the ancient kings' virtuous conduct, do not dare to practice.[16] These must be put on your breast(heart) to the end of your life.

Those who pursue learning should persistently face towards the Way and should not be overcome by external things. The improper ones among external things should not be kept in mind at all. In the place where village people gather if they set chess, paduk(go), dies and sticks and so on and play [them], then do not set eyes on [them] but stand back and retreat. In the place where village people gather if they set chess, paduk(go), dice and sticks and the like, and play [them], then do not set eyes on [them] but stand back and retreat. If you happened to meet entertainer-courtesans singing and dancing, then it would be necessary to avoid and leave there. If you encounter a big gathering in a village and by chance elders force you to stay, so you cannot avoid and retreat, then, despite seating there, tidy up your appearance and clean up your heart. Do not let lewd sounds or licentious sights have an influence on yourself. Being in feast and drinking wine, do not get heavily drunk. When feeling a bit tipsy, it is proper to stop [drinking]. All food should be eaten in proper amounts. Do not eat heartily lest it become harmful to qi, or spirits. Words and laughter should be succinct and cautious. Do not be so vociferous that it may cross the line of moderation. Moving and resting should be at ease and with care. Do not lose your dignity by coarseness and frivolity.

If there is work to do, then treat it with principle. When reading a book, exhaustively investigate principle with sincerity. Except for these two cases, sit in silence and concentrate your mind. Let it be calm and quiet so that there should be no disorderly-generated thoughts. It is proper to make it awake and alert without lapse into being beclouded. Correcting inner being with the so-called reverence is like this.

One must rectify the body and mind so that one's exterior and interior may be consistent. When being in darkness, act like being in the light. When alone, act like being in public. Let this mind be like the bright sun in the blue sky that people are able to see.

Always remember this saying: "Even if, by committing one unjust act or murdering one innocent person, I can get a whole world, I will not do it." [17] Keep this intent in mind.

03-14 居敬以立其本 窮理以明乎善 力行以踐其實 三者 終身事業也 By abiding in reverence, establish the foundation. By exhaustively investigating principle, clearly understand the good. By diligently doing [it], carry it out in actual practice. These three shall be one's business to the end of life.

"Have no evil thoughts"[18] and "Have no irreverence."[19] It is only these two phrases that will never be exhausted despite receiving and applying [them] to one's whole life. One ought to hang the phrases on the wall so that they may not be forgotten even for a moment.

03-16 每日 頻自點檢 心不存乎 學不進乎 行不力乎 有則改之 無則加勉 孜孜母怠斃而後已 On each day frequently examine yourself by asking, "Has my heart not been preserved?" or "Was there no progress made in learning?" or "Was there no effort made in practice?" If there was such case, correct it. If there was no, exert yourself more assiduously without laziness. You may stop after death.

|

- Discussion Questions:

Footnotes

- ↑ For more information, see Yi Kwang Ho 2012.

- ↑ http://gutenberg.us/details.aspx?bookid=wplbn0003466791 (last retrieval Feb 17, 2017).

- ↑ For more information, see Kim 1973, 27-28.

- ↑ For more information, see Pak 2009, 164.

- ↑ Translating the title has been tried several times: On the Secret of Expelling Ignorance (Yi Kwang Ho, 2012), Essentials of Enlightenment (Yi T’aejun 2009, 148), Important Methods of Eliminating Ignorance (Haboush 1999, 23). However, none of them delivers the subtle meaning of the character ‘Gyeok 擊’, so this version attempts to convey its literal meaning by translating it into "Breaking." And moreover, the meaning of the character ‘Mong 蒙’ is not limited to mere ignorance. It should be extended to all kinds of "folly" which was adopted here. The expression "Breaking Folly's Hold" was borrowed from Waltke's commentary on the Book of Proverbs (Waltke 2005, 216).)

- ↑ For more information, see Yi Dong-in 2014, 24.

- ↑ It was written three years after the death of his beloved mother in 1551. For further details, see Pokorny and Chang 2011, 142: “The so-called Jagyeongmun 自警文 (Written to Alert Myself) is relatively brief, yet marks a watershed in Yulgok’ intellectual development. It represents his written resolution to henceforth wholeheartedly adhere to Confucian teachings while keeping any ‘false doctrines’ (wihak 僞學) at distance. The authoring of the Jagyeongmun concludes his yearlong sojourn in a Buddhist monastery at Geumgangsan 金剛山.”

- ↑ Analects 4.9. The Master said, "A scholar, whose mind is set on truth, and who is ashamed of bad clothes and bad food is not fit to be discoursed with." 子曰 士志於道而恥惡衣惡食者 未足與議也

- ↑ Analects 1.8. The Master(Confucius) said, "If the scholar be not grave, he will not call forth any veneration, and his learning will not be solid. Hold faithfulness and sincerity as first principles. Have no friends not equal to yourself. When you have faults, do not fear to abandon them." 子曰 君子不重則不威 學則不固 主忠信 無友不如己者 過則勿憚改

- ↑ Huang Mianzhai is also known as Huang Kan (1152-1221). As Zhu Xi's pupil and son-in-law, he wrote the biographical account 行狀 of Zhu Xi.

- ↑ Liji. Yu Zao: He did not move his feet lightly, nor his hands irreverently. His eyes looked straightforward, and his mouth was kept quiet and composed. No sound from him broke the stillness, and his head was carried upright. His breath came without panting or stoppage, and his standing gave (the beholder) an impression of virtue. His looks were grave, and he sat like a personator of the dead. When at leisure and at ease, and in conversation, he looked mild and bland. 足容重,手容恭,目容端,口容止,聲容靜,頭容直,氣容肅,立容德,色容莊,坐如尸,燕居告溫溫。

- ↑ Analects 16.13. "He was standing alone once, when I passed below the hall with hasty steps" 嘗獨立 鯉趨而過庭

- ↑ Analects 16.10. Confucius said, "The superior man has nine things which are subjects with him of thoughtful consideration. In regard to the use of his eyes, he is anxious to see clearly. In regard to the use of his ears, he is anxious to hear distinctly. In regard to his countenance, he is anxious that it should be benign. In regard to his demeanor, he is anxious that it should be respectful. In regard to his speech, he is anxious that it should be sincere. In regard to his doing of business, he is anxious that it should be reverently careful. In regard to what he doubts about, he is anxious to question others. When he is angry, he thinks of the difficulties (his anger may involve him in). When he sees gain to be got, he thinks of righteousness." 孔子曰, 君子有九思, 視思明, 聽思聰, 色思溫, 貌思恭, 言思忠, 事思敬, 疑思問, 忿思難, 見得思義.

- ↑ Analects 12.1. The Master replied, "Look not at what is contrary to propriety; listen not to what is contrary to propriety; speak not what is contrary to propriety; make no movement which is contrary to propriety." 子曰:「非禮勿視,非禮勿聽,非禮勿言,非禮勿動。」

- ↑ Analects 13.19. The Master said, "It is, in retirement, to be sedately grave; in the management of business, to be reverently attentive; in intercourse with others, to be strictly sincere." 子曰:「居處恭,執事敬,與人忠。」

- ↑ Xiao Jing. Filial Piety in High Ministers and Great Officers: They do not presume to wear robes other than those appointed by the laws of the ancient kings, nor to speak words other than those sanctioned by their speech, nor to exhibit conduct other than that exemplified by their virtuous ways. 《孝經·卿大夫》: 非先王之法服不敢服,非先王之法言不敢道,非先王之德行不敢行。

- ↑ Mengzi. Gong Sun Chou I. 2. 24. And none of them, in order to obtain the throne, would have committed one act of unrighteousness, or put to death one innocent person. In those things they agreed with him.' 行一不義、殺一不辜而得天下,皆不為也。

- ↑ Analects. 2.2. The Master said, "In the Book of Poetry are three hundred pieces, but the design of them all may be embraced in one sentence - 'Having no depraved thoughts.'" 子曰 詩三百 一言以蔽之 曰思無邪.

- ↑ Liji. Qu Li I. The Summary of the Rules of Propriety says: Always and in everything let there be reverence; with the deportment grave as when one is thinking (deeply), and with speech composed and definite. 《曲禮》曰:「毋不敬,儼若思,安定辭。」

Further Readings

Haboush, JaHyun Kim, and Martina Deuchler, eds. 1999. Culture and the State in Late Chosŏn Korea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

Han, Hyeong-jo 한형조. 2015. “Yulgok’ui sasip’isejak Gyeongmong yogyeol’ui seomun’gwa iljang’eul tong’hae ing’nEun yugyo simhak’ui kichowa kangnyeong” 율곡의 42세 작, 『격몽요결』의 서문과 1장을 통해 읽는 유교 심학의 기초와 강령 [Reading “The Secret of Expelling Ignorance”]. 정신문화연구 [Korean Studies Quarterly] 38(3): 7-29.

Kalton, Michael C. 1988. To Become a Sage: The Ten Diagrams on Sage Learning, New York: Columbia University Press.

Kim, Han-sik 김한식. 1997. “Haengjang’eul tong’hae bon Yulgok’ui sasangsegye” 行狀을 통해 본 율곡의 사상세계 [Yulgok's Philosophical View Through His Posthumous Biography]. 한국정치학회보 [Korean Political Science Review] 30(4): 21-38.

Legge, James. The Chinese Classics. vol. 1, part 2. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1870. <http://ctext.org/mengzi> (last retrieval Feb 2, 2017).

Pak, Kyun-seop 박균섭. 2009. “Eunbyeongjeongsa yeongu: hangmun’gwa hakpung” 은병정사 연구: 학문과 학풍 [Study of Eunbyeong Private Academy: Learning and Academic Tradition]. 율곡사상연구 [Study of Yukgok's Philosophy] 19: 163-196.

Pokorny, Lukas, and Wonsuk Chang. 2011. “Resolutions to Become a Sage: An Annotated Translation of the Jagyeongmun.” Studia Orientalia Slovaca 10 (1): 139-54.

Waltke, Bruce K. 2005. The Book of Proverbs: Chapters 15-31, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Yi, Dong-in 이동인. 2014. “Gyeongmong yogyeol’eul tong’hae bon Yulgok’eu sasang’gwa saeg’ae” 『격몽요결(擊蒙要訣)』을 통해 본 율곡의 사상과 생애 [Life and Thoughts of Yulgok in Reference to His Work Gyeongmong yogyeol’]. 사회사상과 문화 [Journal of Social Thoughts and Culture] 29: 23-50.

Yi, Kwang Ho 이광호. 2012. Gyeongmong yogyeol 격몽요결 [On the Secret of Expelling Ignorance]. Seoul 서울: Luxmedia 럭스미디어. <http://gutenberg.us/details.aspx?bookid=wplbn0003466791> (last retrieval Feb 17, 2017).

Yi, I 李耳. Gyeongmong yogyeol 擊蒙要訣 [Key to Breaking Folly's Hold]. 栗谷先生全書 卷27 [Complete Works of Yulgok, vol. 27]. <http://db.itkc.or.kr/index.jsp?bizName=MK> (last retrieval July 21, 2017).

Yi, T’aejun. 2009. Eastern Sentiments. Translated by Janet Poole. New York: Columbia University Press.