"(Translation) 文憲書院學規"의 두 판 사이의 차이

(→Introduction) |

(→Introduction) |

||

| 24번째 줄: | 24번째 줄: | ||

The first Confucian academy 書院 appeared on the Korean peninsula in 1543 with the establishment of the White Cloud Grotto Academy 白雲洞書院 by Chu Sebung 周世鵬 (1495-1554) in P'unggi, Kyŏngsang-Province. This academy, founded to honor the Koryŏ scholar An Hyang 安珦 (1243-1306), who is usually credited with bringing Neo-Confucian teachings from China to Korea, in 1550 was royally chartered to the name Sosu Academy 紹修書院 on the advice of T'oegye Yi Hwang 退溪 李滉 (1501-1570).<ref> See Hejtmanek, Milan; "The Elusive Path to Sagehood. Origins of the Confucian Academy Systemn Chosŏn Korea“, in: Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 26/2 (December 2013), p. 233–268. </ref> | The first Confucian academy 書院 appeared on the Korean peninsula in 1543 with the establishment of the White Cloud Grotto Academy 白雲洞書院 by Chu Sebung 周世鵬 (1495-1554) in P'unggi, Kyŏngsang-Province. This academy, founded to honor the Koryŏ scholar An Hyang 安珦 (1243-1306), who is usually credited with bringing Neo-Confucian teachings from China to Korea, in 1550 was royally chartered to the name Sosu Academy 紹修書院 on the advice of T'oegye Yi Hwang 退溪 李滉 (1501-1570).<ref> See Hejtmanek, Milan; "The Elusive Path to Sagehood. Origins of the Confucian Academy Systemn Chosŏn Korea“, in: Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 26/2 (December 2013), p. 233–268. </ref> | ||

| − | Confucian academies had already existed in China since the Tang-Dynasty and had developed from librarian institutions into fully-fledged schools contending with, and sometimes replacing, the official state school system. During the Northern Song-Dynasty many academies flourished and gained far-reaching reputations. Later some became associated with the proliferation of the Zhu Xi's teachings, as their private setting provided space to teach interpretations of the Confucian canon outside of the government orthodoxy.<ref> See Chan, Wing-tsit: "Chu Hsi and the Academies“, in: de Bary, Wm. T./Chaffee, J. W., Neo-Confucian Education. The Formative Stage, Berkeley 1989, p. 389-413 </ref> Most famous among these academies was the White Deer Grotto academy 白鹿洞書院 restored by Zhu Xi himself in 1180 and often understood as the essential academy model in Korea. | + | Confucian academies had already existed in China since the Tang-Dynasty and had developed from librarian institutions into fully-fledged schools contending with, and sometimes replacing, the official state school system. During the Northern Song-Dynasty many academies flourished and gained far-reaching reputations. Later some became associated with the proliferation of the Zhu Xi's teachings, as their private setting provided space to teach interpretations of the Confucian canon outside of the government orthodoxy.<ref> See Chan, Wing-tsit: "Chu Hsi and the Academies“, in: de Bary, Wm. T./Chaffee, J. W., Neo-Confucian Education. The Formative Stage, Berkeley 1989, p. 389-413 </ref> Most famous among these academies was the White Deer Grotto academy 白鹿洞書院 restored by Zhu Xi himself in 1180 and often understood as the essential academy model in Korea. |

| − | Backed by royal endowments of land, slaves, books and other resources many academies gained fame and authority in their localities. Being part of Yangban status culture, they began to dominate their local societies and often pressed the local population into their service. With the increasing factional political struggle gripping Korean court politics in the latter half of the Chosŏn-period academies often functioned as economic and political bases for their respective factions. Especially during the 18th and 19th century, they were viewed as limiting state authority outside the capital and putting a financial burden on the people. Therefore, after several failed attempts to curb the power of the academies, in 1871 the royal regent Hŭngsŏn Taewŏn'gun 興宣大院君 (1820-1898) in his reforms tried to limit the number of Confucian academies to 47, preserving only some important royally chartered academies and abolishing most of the others. | + | Already known in Korea since at least the early 15th century,<ref> See http://sillok.history.go.kr/id/wda_10011003_012, Already in 1418 King Sejong tried to foster the spread of Confucian academies by giving incentives to officials for founding them </ref> Confucian academies spread rapidly in Chosŏn from the second half of the 16th century and by 1720 their numbers had already reached about 400 individual institutions.<ref> See Moon, Tae-soon; "Kyoyuk kigwan-ŭrosŏ sŏwŏn-ŭi sŏnggyŏk yŏn'gu [A Study of the Character of Academies as Educational Institution]“, in: Kyoyuk paljŏn yŏn'gu, 20/1 (June 2004), p. 7-21 </ref> Backed by royal endowments of land, slaves, books and other resources many academies gained fame and authority in their localities. Being part of Yangban status culture, they began to dominate their local societies and often pressed the local population into their service. With the increasing factional political struggle gripping Korean court politics in the latter half of the Chosŏn-period academies often functioned as economic and political bases for their respective factions. Especially during the 18th and 19th century, they were viewed as limiting state authority outside the capital and putting a financial burden on the people. Therefore, after several failed attempts to curb the power of the academies, in 1871 the royal regent Hŭngsŏn Taewŏn'gun 興宣大院君 (1820-1898) in his reforms tried to limit the number of Confucian academies to 47, preserving only some important royally chartered academies and abolishing most of the others. |

The Munhŏn Academy 文憲書院 was also founded by Chu Sebung during his time in Haeju in the Hwanghae-Province, modern day North Korea, as Suyang Academy 首陽書院 in 1549. It received a royal charter in 1555 and was renamed the Munhŏn Academy, an allusion to Koryŏ scholar Ch’oe Ch’ung 崔沖 (984~1068), a native of Haeju, who was also enshrined in the academy. Its regulations were drafted by the famous scholar Yulgok Yi I 栗谷 李珥 (1536-1584) in 1578. By this time Yulgok had actively served in different post of the government and was deeply involved in reforming the educational system of the state, as for example in his work "Model for Schools" 學校模範, suggesting curricula and teaching methods for the schools. | The Munhŏn Academy 文憲書院 was also founded by Chu Sebung during his time in Haeju in the Hwanghae-Province, modern day North Korea, as Suyang Academy 首陽書院 in 1549. It received a royal charter in 1555 and was renamed the Munhŏn Academy, an allusion to Koryŏ scholar Ch’oe Ch’ung 崔沖 (984~1068), a native of Haeju, who was also enshrined in the academy. Its regulations were drafted by the famous scholar Yulgok Yi I 栗谷 李珥 (1536-1584) in 1578. By this time Yulgok had actively served in different post of the government and was deeply involved in reforming the educational system of the state, as for example in his work "Model for Schools" 學校模範, suggesting curricula and teaching methods for the schools. | ||

2017년 7월 20일 (목) 16:47 판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | The Regulations of the Munheon Academy | |

| Chinese | 文憲書院學規 | |

| Korean(RR) | 문헌서원학규(Munheonseowon hakgyu) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Literati writings | |

| Type | Regulations | |

| Author(s) | 栗谷 李珥 | |

| Year | 1578 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | ||

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2017 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | King Kwong Wong (Translation), Martin Gehlmann (Introduction) | |

| Year | 2017 | |

목차

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Original Script

- 3 Discussion Questions

- 4 Further Readings

- 5 References

- 6 Translation

- 6.1 Student 1 : (Hu Jing)

- 6.2 Student 2 : King Kwong Wong

- 6.3 Student 3 : (Zhijun Ren)

- 6.4 Student 4 : Martin

- 6.5 Student 5 : (Young Suk)

- 6.6 Student 6 : (Do hee Jeong)

- 6.7 Student 7 : (Irina)

- 6.8 Student 8 : (Kim Young)

- 6.9 Student 9 : (Masha)

- 6.10 Student 10 : (Jong Woo Park)

- 6.11 Student 11 : (Kanghun Ahn)

- 6.12 Student 12 : (Write your name)

- 6.13 Student 13 : (Write your name)

- 6.14 Student 14 : (Write your name)

- 7 Further Readings

Introduction

The first Confucian academy 書院 appeared on the Korean peninsula in 1543 with the establishment of the White Cloud Grotto Academy 白雲洞書院 by Chu Sebung 周世鵬 (1495-1554) in P'unggi, Kyŏngsang-Province. This academy, founded to honor the Koryŏ scholar An Hyang 安珦 (1243-1306), who is usually credited with bringing Neo-Confucian teachings from China to Korea, in 1550 was royally chartered to the name Sosu Academy 紹修書院 on the advice of T'oegye Yi Hwang 退溪 李滉 (1501-1570).[1]

Confucian academies had already existed in China since the Tang-Dynasty and had developed from librarian institutions into fully-fledged schools contending with, and sometimes replacing, the official state school system. During the Northern Song-Dynasty many academies flourished and gained far-reaching reputations. Later some became associated with the proliferation of the Zhu Xi's teachings, as their private setting provided space to teach interpretations of the Confucian canon outside of the government orthodoxy.[2] Most famous among these academies was the White Deer Grotto academy 白鹿洞書院 restored by Zhu Xi himself in 1180 and often understood as the essential academy model in Korea.

Already known in Korea since at least the early 15th century,[3] Confucian academies spread rapidly in Chosŏn from the second half of the 16th century and by 1720 their numbers had already reached about 400 individual institutions.[4] Backed by royal endowments of land, slaves, books and other resources many academies gained fame and authority in their localities. Being part of Yangban status culture, they began to dominate their local societies and often pressed the local population into their service. With the increasing factional political struggle gripping Korean court politics in the latter half of the Chosŏn-period academies often functioned as economic and political bases for their respective factions. Especially during the 18th and 19th century, they were viewed as limiting state authority outside the capital and putting a financial burden on the people. Therefore, after several failed attempts to curb the power of the academies, in 1871 the royal regent Hŭngsŏn Taewŏn'gun 興宣大院君 (1820-1898) in his reforms tried to limit the number of Confucian academies to 47, preserving only some important royally chartered academies and abolishing most of the others.

The Munhŏn Academy 文憲書院 was also founded by Chu Sebung during his time in Haeju in the Hwanghae-Province, modern day North Korea, as Suyang Academy 首陽書院 in 1549. It received a royal charter in 1555 and was renamed the Munhŏn Academy, an allusion to Koryŏ scholar Ch’oe Ch’ung 崔沖 (984~1068), a native of Haeju, who was also enshrined in the academy. Its regulations were drafted by the famous scholar Yulgok Yi I 栗谷 李珥 (1536-1584) in 1578. By this time Yulgok had actively served in different post of the government and was deeply involved in reforming the educational system of the state, as for example in his work "Model for Schools" 學校模範, suggesting curricula and teaching methods for the schools.

His regulations for the Munhŏn Academy can be viewed in a similar light, trying to correcting the perceived ills of his time like nepotism and emphasizing the importance of seniority in all areas of life in the academy. However compared to other academy regulations of the time the Munhŏn Academy rules are less concerned with promoting a more private education away from studying for success in the examinations than for example T'oegye Yi Hwang's regulations for the Isan Academy 伊山書院. Yulgok also viewed the academy as to be embedded in its local community and tried to instate close connections through community compacts and granaries. The Munhŏn Academy was to be demolished under the command of the king regent in 1871.

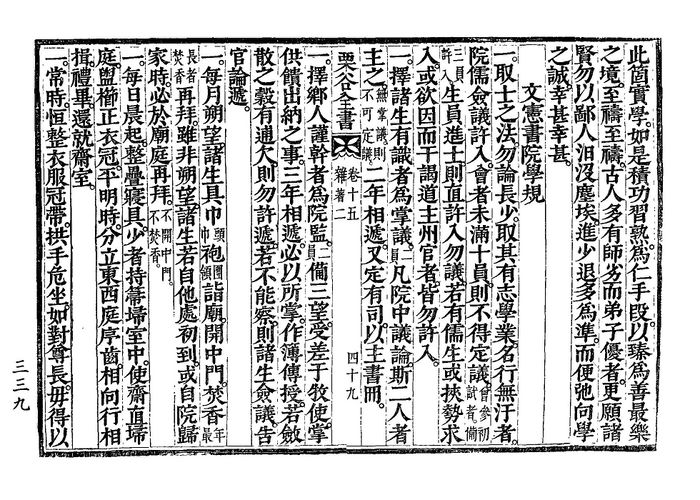

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

文憲書院學規

7. 一。凡居處必以便好之地。推讓長者。毋或自擇其便。年十歲以長者出入時。少者必起。 一。凡食時。長幼齒坐。於飮食不得揀擇取舍。常以食無求飽爲心。

|

School Regulations of the Munhŏn Academy One. As for the method of selecting literati, [enroll students] regardless of age. Select students from those who have the determination in the undertaking of learning, with untainted reputation and behavior. The admission should be discussed by the academy faculty. Should the number of the committee member be less than ten, the meeting is invalid. (In the case of candidates who have attended the preliminary examination, they can be enrolled if there are more than three candidates.) For those who have passed the preliminary or higher level of civil service examinations, they can be admitted directly without discussion. Should there be any Confucian students who rely on the powerful to seek admission, or for that reason ask favors from the provincial governor or prefecture officials, they are not allowed to be admitted. One. Choose among the students those who are erudite as student chiefs (two members). For every discussion meeting within the academy, these two chair them. (If no chief [is presented in the meeting], then the meeting is invalid.) Their term is two years. In addition, a student official should be appointed to manage books. One. Select diligent and hardworking local persons as the academy overseer (two members). Prepare three candidates to be dispatched by the county magistrate. They are in charge of the matter regarding the income and expenditure of sacrificial rites. Their term is three years. For what they are in charge of, they have to maintain bookkeeping for later record. Should the income and expenditure of grain have any discrepancy, they are not allowed to be dismissed. When the reason is unable to be discerned, all the students should form a council to discuss and report to officials about their dismissal. One. Every first and fifteenth of the month, all students have to don their headgear (cap), and gowns (circular collar-robes) to pay respects at the shrine. Open the middle gate, light incense (the oldest lights the incense), and bow again. Even it is not the first or fifteenth day of the month, if students arrive from a different place for the first time, or when students go back home, they must bow to the shrine again. (Without opening the middle gate and lighting incense.) One. Everyday get up at daybreak. Tidy up and stack up your bedding. The younger students should hold the broom and sweep the room. Order the student-on-duty to sweep the courtyard. Wash your face, comb your hair, and adjust your attire. At sunrise, line up in two ranks on the eastern and western sides of the courtyard respectively according to seniority. Face each other and bow with hands clasped. After this ritual is completed, return to the classroom. One. Ordinarily, always adjust your attire, cap, and sash, cup your hands before your chest, and sit solemnly, just as you treat honorable seniors. Do not serve your own convenience by wearing comfortable clothes. (You must wear straight-collar.) Also, do not wear resplendent and beautiful attire that is near extravagant. As for desk, books, brush, ink stone and the likes, you should put them in place tidily. Do not leave them disorderly and untidily. You must write squarely in regular script style. Do not write on the windows, doors, and walls. One. For dwelling places, you should yield convenient and comfortable places to seniors. Do not even by mistake choose convenience for yourself. Whenever seniors, who are ten years or above elder, enter or exit, the younger ones should stand up. One. While having meals, all students sit according to seniority. Do not choose your food. Always have in mind that you should not sate your hunger fully. One. While reading, keep your body straight and cup your hands and sit solemnly. Focus your mind and carry through your will. Work hard at exhausting the right meaning. Do not look at each other and chat. One. As for speaking, be cautious at the language. Do not utter that which is not considered as classics nor propriety and right. Do not talk about licentious, disrespectful, baffling, disorderly, and occult stories. Do not speak of others' mistakes. Do not discuss politics of the court. Do not comment on the success and failure of officials at each administrative unit. One. Friends and peers should strive to be harmonious and respectful to each other. Correct each other with mistakes and reproach each other with good intention. Do not boast your status, wisdom, talent, father and brother, knowledge, so as to be arrogant to your peers. Moreover, do not ridicule and mock your peers. And do not play pranks. Violator will be dismissed from his seat. (This refers to ostracizing. Before a student is released from ostracization, he should face the chastisement of the full house.) One. From the moment one wakes up in the early morning until he goes to bed at night, throughout the entire day, there must be things that one attends to. Whether reading a book, composing a treatise, discussing argumentation and reason, raising questions regarding lectures, or asking clarification about instructions, nothing but the undertaking of learning. As for one's leisure time or swimming in the streams, everyone, likewise, should behave calmly and in orderly fashion. Follow the order of seniority. At dusk, one should light the lantern, and as the night grows long, one should go to bed. If one does not comply with the school regulations, one's manners and bearing would loosen up and become unrestrained. One who is indolent in the undertaking of learning will be dismissed from his seat. If one does not repent and mend one's ways, he will be expelled from the academy. (Those who are expelled from the academy, their names are removed from the roaster.) One. Books within the academy should not be carried out of the gate. If one violates [this regulation], he will be punished. In the case of a serious offense, he will be expelled from the academy. In the case of a light offense, he will be dismissed from his seat. One. If one does not participate in the sacrificial rites of Spring and Autumn without any reason, he will be dismissed from his seat. One. Among those enrolled in the roster, if one behaves unrulily and taints the Confucian custom, his case will be discussed in the council and he will be removed from the roster. One. In the first months of the Four Seasons, the student chiefs will meet all students at the academy, discussing school regulations and examining their success and failure. Those who do not attend without providing reasons will be dismissed from their seats. (Those who have reasons should have a list to state their reasons.) Everyone who enter the academy for the first time should read the school regulations prior to his admission. |

Discussion Questions

- Considering these regulations How was the life of academy students? Were these rules kept well? If not, are there any records showing the Chosŏn Confucian students deviation from their tightly structured routine?

- The rules, such as not writing on windows and walls, implied that there were such precedents. For the modern readers who went through the education system anywhere in the world, this kind of rules are easy to relate to and understand. What does it say about universal human behavior and education process?

- Among Yi I's regulations, which clause emphasizes the practical aspect of communal living, and which clause focuses on cultivating moral principles? Yi I seems to place great emphasis on individual cultivation and the proper relation between peers. What does it tell us about Yi I’s envisioning of an ideal academy? On the whole, do you find the rules practical or idealistic? Why?

- There are documents similar to the regulations written by Yi I. They are, in particular, closely related to those written by Pak Se-ch'ae 朴世采 (1631-95). Pak was one of Yi I's disciples who belonged to the Sŏin 西人 (Westerner) faction. Does this mean that the regulations of the Munhŏn Academy reflected the mind of the Sŏin faction? Did the factions and literati purges shape the writing of regulations?

- What overarching Confucian values do you think are being emphasized in these regulations? Is the values emphasized by Yi I universal--shared by Confucian societies in other parts of the world--or specific to Korea?

- The regulations of the Munhŏn Academy show that in the past education had its main function of not only gaining knowledge but of building up the character and habits of learners. To what extent do modern schools and universities have this function? To what extent does a student's success nowadays depends on his knowledge and to what extent it depends on his behavior?

- Can you see any remaining effect of these regulations on Korean culture today? Which of the listed rules are outdated in modern Korea and which are still in practice? In modern standards, such a rule might come off as unreasonable and oppressive to the younger. What is the Confucian logic for defending this rule, and how would you be able to justify it?

Further Readings

References

- ↑ See Hejtmanek, Milan; "The Elusive Path to Sagehood. Origins of the Confucian Academy Systemn Chosŏn Korea“, in: Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 26/2 (December 2013), p. 233–268.

- ↑ See Chan, Wing-tsit: "Chu Hsi and the Academies“, in: de Bary, Wm. T./Chaffee, J. W., Neo-Confucian Education. The Formative Stage, Berkeley 1989, p. 389-413

- ↑ See http://sillok.history.go.kr/id/wda_10011003_012, Already in 1418 King Sejong tried to foster the spread of Confucian academies by giving incentives to officials for founding them

- ↑ See Moon, Tae-soon; "Kyoyuk kigwan-ŭrosŏ sŏwŏn-ŭi sŏnggyŏk yŏn'gu [A Study of the Character of Academies as Educational Institution]“, in: Kyoyuk paljŏn yŏn'gu, 20/1 (June 2004), p. 7-21

Translation

Student 1 : (Hu Jing)

1. 一。取士之法。勿論長少。取其有志學業。名行無汚者。院儒僉議許入。會者未滿十員。則不得定議。(曾參初試者。備三員許入。) 生員進士。則直許入勿議。若有儒生或挾勢求入。或欲因而干謁道主州官者。皆勿許入。

As to the way to select literati, [enroll students] regardless of age. Select students from those who have the will to devote themselves to study, with unstained names and behavior. The admission should be discussed by the academy faculty. Should the number of the committee member be less than ten, any discussion is invalid. (In the case of candidates who have attended the preliminary examination, students can be enrolled if there are more than three candidates.) As to candidates who have passed the preliminary examination, they could be admitted without discussion. Should there are any Confucian students who coerce the admission or pull the wires of province or prefecture officials, the enrollment is forbidden.

- Discussion Questions:

1. In the Joseon dynasty, how did the students make a choice on which academy to attend? Given that the students make the decision based on the master of the academy, how did you get the information about that?

2. We can learn from the text that the academy holds sacrifice regularly. How can we understand the sacrifice cultrue in the Confucianism?

Student 2 : King Kwong Wong

2. 一。擇諸生有識者爲掌議(二員)。凡院中議論。斯二人者主之。(無掌議。則不可定議。) 二年相遞。又定有司。以主書冊。

Choose among the students those who are erudite as student presidents (two members). For every discussion meeting within the academy, these two chair them. (If no president [is presented in the meeting], then it is not allowed to reach a decision.) Both will be substituted in two years. In addition, a student official should be appointed to manage books.

- Discussion Questions:

- How did Yi I and his academy enforce its regulations? Given the high-handed nature of the regulations, how do they reflect the quality of students?

- Why do the regulations forbade the discussion of politics? Considering the last literati purge happened in 1545, would it be a consequence of the literati purges during the Chosŏn period?

Student 3 : (Zhijun Ren)

一。擇鄕人謹幹(diligent and hardworking)者爲院監overseers(二員)。Select two diligent and hardworking persons from the locals, let them be the overseers of the academy. 備三望。受差于牧使。掌供饋出納之事。they are appointed by the local governor. they would be in charge of the matters of income and expenditure. 三年相遞。必以所掌。作簿傳授。they will alternate every three years. they have to maintain bookkeeping for what they are in charge. 若斂散之穀有逋欠。則勿許遞。 若不能察。則諸生僉議(public discussion)。告官論遞。

- Discussion Questions:

Yi I seems to place great emphasis on individual cultivation and the proper relation between peers. What does it tell us about Yi I’s envisioning of an ideal academy?

Student 4 : Martin

一。每月朔望。諸生具巾 (頭巾) 袍 (團領) 詣廟。開中門焚香. 年最長者焚香 再拜。雖非朔望。諸生若自他處初到。或自院歸家時。必於廟庭再拜。不開中門。不焚香。

One. Every first and fifteenth of the lunar month, all students have to don their headgear (cap), and gowns (circular collar-robes) to pay respects at the shrine. Open the middle door, and light incense (the oldest lights the incense), bow down twice. Even if it is not the first or fifteenth day of the month, if literati from a different place are visiting for the first time, or when students go back home, they must bow to the shrine twice, then do not open the middle door and do not light incense.

- Discussion Questions:

1. Considering that students of different (yangban-) backgrounds could enter the academies, do you think Yulgoks emphasis on the order of seniority could have been problematic at times? What times could that be?

2. Looking at modern school systems some of this rules seem quite obvious, check your schools regulations for similarities and differences?

Student 5 : (Young Suk)

每日晨起。整疊寢具。少者持箒埽室中。使齋直埽庭。盥櫛正衣冠。平明時。分立東西庭序齒。相向行相揖。禮畢。還就齋室。

Everyday get up at daybreak. Tidy up and fold your bedding away. The younger students should sweep up the room. Let the errand boy arrange the court yard. Wash your face, comb your hair, and adjust your attire. At sunrise line up in two ranks according to age, east and west in the courtyard. Face each other and bow down with your hands together. On completion of this ritual, immediately return to the lecture room.

- Discussion Questions:

1. Yi Yulgok wrote the regulations in a meticulous manner. Is this based on his belief in Confucian philosophy of the ki (氣) school that relates the essence of human mind (理) and human behavior(氣) not to be separate but one under the non-dual principle?

2. The name of the academy originates from Ch'oe Ch'ung's (984-1098, Koryŏ dynasty) posthumous name, Munhŏn (文憲). Ch'oe Ch'ung was called 'Confucius of the Land East of the Sea' and the founder of the first private Confucian Academy in Korea. Ch'oe must have composed the regulations for his academy too. If so, what connections might there be between the original Ch'oe's and Yi's regulations?

Student 6 : (Do hee Jeong)

一。常時。恒整衣服冠帶。拱手危坐。如對尊長。 First. In ordinary times, you always adjust your cloths, cap, sash1) and salute with the hands folded and sit gingerly, just as you encounter honorable senior

毋得以褻服自便。[必著直領] Do not consult your own convenience by wearing comfortable clothes. [you must wear jingnyeong 2)]

且不得著華美近奢之服。 And do not wear clothes which is resplendent and extravagant

凡几案書冊筆硯之具。皆整置其所。毋或亂置不整。 you should orderly replace a table, books, a brush, an inkstone in place. If and when do not leave disorderly those(?)

作字必楷正。毋得書于窓戶壁上。 When writing, you must write in regular script style and do not write on the windows and doors and the wall

1)cloths worn by the literati

2)coat with a straightened collar, wearing in from the the Late Goryeo Dynasty to Joeseon Dynasty

- Discussion Questions:

There are similar documents as these regulations written by Yi I. They are in particular closely related to those written by Park Sech'e (朴世采, 1631-95). Park was one of Yi I's disciples who belonged to Soe-in (西人) school. Does this mean that the Munheon Academy regulations reflected the mind of Soe-in school? Did the factions likewise influence the academies in writing regulations during the Joseon dynasty?

Student 7 : (Irina)

- Discussion Questions:

The Regulations of the Munheon Academy show that in the past education had as its main function not only gaining of knowledge but the build-up of the character and habits of learners. To what extent today schools and universities have this function? To what extent does a student's success nowadays depends on his knowledge and to what extend it depends on his behavior.

Which of the listed rules are outdated in modern Korea and which are still in practice?

7. 一。凡居處必以便好之地。推讓長者。毋或自擇其便。年十歲以長者出入時。少者必起。

If the place to stay is nice and comfortable, you should give it to the senior. It is not acceptable to prefer the convenience for yourself. When someone who is 10 or more years elder comes in or out, the younger ones should stand up.

一。凡食時。長幼齒坐。於飮食不得揀擇取舍。常以食無求飽爲心。

While having meal, seniors sit first. It is not acceptable to select your food. Always have in mind that you should not sate your hunger fully.

Student 8 : (Kim Young)

8.。一。讀書時。必端拱危坐。專心致志。務窮義趣。毋得相顧談話。一。凡言語必愼重。非文字禮法則不言。毋談淫褻悖亂神怪之事。毋談他人過惡。毋談朝廷政事。毋說州縣官員得失。 一。朋友務相和敬。相規以失。相責以善。毋得挾貴挾賢挾才挾父兄挾多聞見。以驕于儕輩。且不得譏侮儕輩。以相戲謔。違者黜座。(卽損徒也。解損時。必滿座面責。)

One. When reading, organize your body and sit solemnly. Focus your mind and extend your intent. Work hard at exhausting the meaning. Do not look at each other and chat.

One. As to speaking, the language should be cautious. Do not talk about what is not written in the classics as propriety and ritual. Do not talk about licentious, dirty, destructive, disorderly, and occult stories. Do not speak of others' mistakes. Do not discuss the politics of the court. Do not bring up the gain and loss of prefects at each administrative unit.

One. Friends should strive to be harmonious and respectful. They should correct each other's mistakes and reproach each other to do better. Do not boast your status, wisdom, talent, father and brother, knowledge, so as to be arrogant to your peers. Moreover, do not ridicule and mock each other. And don't play pranks. Violators will have to leave their seats. (This refers to ostracizing. Before a student is pardoned from ostracization, he should be scolded in front of everyone.)

- Discussion Questions:

1. Among Yulgok's regulations, which clause emphasizes the practical aspect of communal living, and which clause focuses on cultivating moral principles? On the whole, do you find the rules to be more practical or more idealistic? Why?

2. Why do you think it is so important to respect the elderly and prioritize their needs in Confucian society? From modern standards, such a rule might come off as unreasonable and oppressive to the younger. What is the Confucian logic for defending this rule, and how would you be able to justify it?

3. From which classics does Yulgok pull quotations, and what are the meaning and significance of these quotations?

Student 9 : (Masha)

9. 一。自晨起至夜寢。一日之閒。必有所事。或讀書。或製述。或講論義理。或請業請益。無非學業。至於暇時或游泳川上。亦皆從容齊整。長幼有序。昏必明燈。夜久就寢。若不遵學規。威儀放曠。學業怠惰者黜座。不悛則黜院 [黜院者。削其籍。]

From the moment one wakes up in early morning until he goes to bed at night and throughout entire day there must be things one attends to. Reading a book, engaging in composition, discussing argumentation and reason, or asking questions regarding lessons as well as asking for instructions. Nothing but the undertaking of learning. As for one's leisure time or swimming in the streams, everyone, likewise, should behave in a proper manner and in orderly fashion. Follow the order in seniority. At dusk one must light the lantern, and as the night grows long one must go to bed. If one does not comply with the school regulations, one's manners and bearing would loosen up and become unrestrained. One who is indolent in the undertaking of learning will be dismissed from the classroom. If one does not repent and mend one's ways, he will be expelled from the academy. [Ones who are expelled from the academy, their name gets removed from the roaster.]

- Discussion Questions:

1. Many of the listed regulations are common sense in modern Korean society, such as the order of seniority, and are abided to throughout one person's life. What does it imply for the time these regulations were compiled, why were they extensively described? How do they compare to the regulations prescribed in current school environment?

2. What do these particular rules imply about standards of behavior? For example, why would straightened clothes or being tidy and organized matter? What was the role of the academies aside from formal education?

3. The rules, such as not writing on windows and walls, implied that there were such precedents. For the modern readers who went through the education system anywhere in the world this kind of rules are easy to relate to and understand them. What does it say about universal human behavior and education process?

Student 10 : (Jong Woo Park)

10.

一。院中書冊。毋得出于院門。違則罰其主者。重則黜院。輕則黜座。

One. Books belong to the academy should not be moved out of the academy. If one violates it, the violator will be expelled from the academy in the case of a serious offense or he will be removed from his seat in the case of a light offense.

一。春秋祭。無故不參者黜座。

One. If one does not participate in the scarifies rites of spring and autumn without any reason will be removed from his seat.

一。寄名院籍。或有失身毀行。玷辱儒風者。則僉議削籍。

One. Among those enrolled in the roster, if one behaves unrulily and pollutes the custom of Confucius, his case will be discussed in the council and he will be removed from the roster.

- Discussion Questions:

(1) What kind of Confucian culture or values do these regulations represent?

(2) Is what Yi I emphasizes in this document universal--shared by Confucian societies in other parts of the world--or specific to Korea?

(3) Can you see any remaining effect of this (kind of) regulation on Korean culture today?

Student 11 : (Kanghun Ahn)

一。四孟之月。掌議會諸生于院。講議學規。檢察諸生得失。無故不參者黜座。有故則必具單子。告其由。 凡初入院者。必使先讀學規。

Discussion questions: How was the life of Choson's Confucian students in conjunction with such regulations? Were these rules kept well? If not, are there any records showing the Choson Confucians' deviation from their tightly structured routine?

Student 12 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 13 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 14 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions: 1. Among these regulations, which do you think are applicable today, and which inapplicable? 2. What overarching values do you think are being emphasized here in these regulations? 3. Why do you think these rules regulate the ways in which the students conduct their behaviors? 4. What are the rules and regulations from?