"(Translation) 老乞大新釋序"의 두 판 사이의 차이

Jangseogak (토론 | 기여) (→Original Script) |

Jangseogak (토론 | 기여) |

||

| 25번째 줄: | 25번째 줄: | ||

=='''Introduction'''== | =='''Introduction'''== | ||

| − | The ''Nogôldae'' (老乞大, RR: ''Nogeoldae''), translated in English as the ''Old Cathayan'', was a textbook of colloquial northern Chinese that was first written and published in Korea in the 14th century. It consisted in a collection of dialogues built around Korean merchant’s journey from Koryǒ to Beijing and his return to his homeland. During his travel, he would for instance introduce himself to Chinese people, say what classics he likes to read, buy and sell products and discover Beijing. | + | The ''Nogôldae'' (老乞大, RR: ''Nogeoldae''), translated in English as the ''Old Cathayan'', was a textbook of colloquial northern Chinese that was first written and published in Korea in the 14th century. Until now, the exact year of its publication and its author(s) is unknow. |

| + | |||

| + | It consisted in a collection of dialogues built around Korean merchant’s journey from Koryǒ to Beijing and his return to his homeland. During his travel, he would for instance introduce himself to Chinese people, say what classics he likes to read, buy and sell products and discover Beijing. Here an extract of these dialogues to which I added an English translation: | ||

| + | blabla | ||

| + | extract | ||

| + | translation | ||

조선 영조 39년(1763)에 역관 김창조(金昌祚), 변헌(邊憲) 등이 엮은 책. 중국어 학습서로 꾸며진 ≪노걸대≫의 잘못된 곳을 바로잡아 간행하였다. 1책. | 조선 영조 39년(1763)에 역관 김창조(金昌祚), 변헌(邊憲) 등이 엮은 책. 중국어 학습서로 꾸며진 ≪노걸대≫의 잘못된 곳을 바로잡아 간행하였다. 1책. | ||

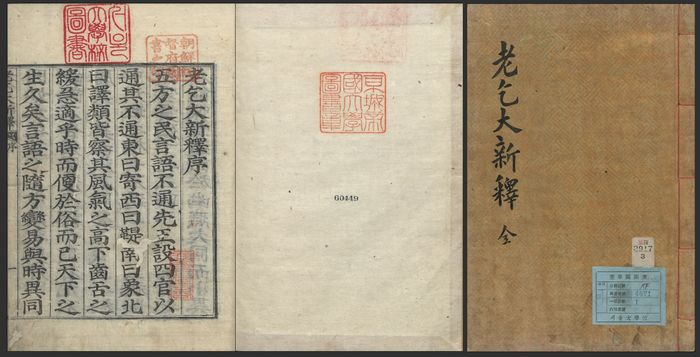

| − | + | The ''Nogôldae'' went through several editions from the 14th to 18th centuries and each consisted in either adding Korean glosses or modifying the original Chinese dialogues. The present New edition of the 'Old Cathayan' (老乞大新釋, MR: ''Nogǒldae Sinsǒk'', RR: ''Nogeoldae Sinseok'') was written in 1761 and proposes a first revision of the Chinese content; colloquial Chinese was likely to have evolved during the three centuries following the first publication of the ''Nogǒldae''. The following extract shows some of the changes operated in comparison with the extract of the original text above: | |

| − | + | blabla | |

| + | extract | ||

| + | translation | ||

| − | + | The preface was not written by ___ but by | |

| + | { {INTRO PREFACE upcoming} } | ||

| + | A corresponding text with gloses, the ''Nogǒldae Sinsǒk Ǒnhae'' (老乞大新釋諺解, RR: ''Nogeoldae Sinseok Eonhae''), was published in 1763 but appears to be no longer extant. | ||

=='''Original Script'''== | =='''Original Script'''== | ||

2018년 7월 21일 (토) 16:36 판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | Preface to the New Edition of the 'Old Cathayan' | |

| Chinese | 老乞大新釋 序 | |

| Korean(RR) | 노걸대신석 서(Nogeoldae Sinseok Seo) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | ||

| Type | ||

| Author(s) | ||

| Year | 1761 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | ||

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2018 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | Younès M'Ghari | |

| Year | 2018 | |

Introduction

The Nogôldae (老乞大, RR: Nogeoldae), translated in English as the Old Cathayan, was a textbook of colloquial northern Chinese that was first written and published in Korea in the 14th century. Until now, the exact year of its publication and its author(s) is unknow.

It consisted in a collection of dialogues built around Korean merchant’s journey from Koryǒ to Beijing and his return to his homeland. During his travel, he would for instance introduce himself to Chinese people, say what classics he likes to read, buy and sell products and discover Beijing. Here an extract of these dialogues to which I added an English translation:

blabla extract translation

조선 영조 39년(1763)에 역관 김창조(金昌祚), 변헌(邊憲) 등이 엮은 책. 중국어 학습서로 꾸며진 ≪노걸대≫의 잘못된 곳을 바로잡아 간행하였다. 1책.

The Nogôldae went through several editions from the 14th to 18th centuries and each consisted in either adding Korean glosses or modifying the original Chinese dialogues. The present New edition of the 'Old Cathayan' (老乞大新釋, MR: Nogǒldae Sinsǒk, RR: Nogeoldae Sinseok) was written in 1761 and proposes a first revision of the Chinese content; colloquial Chinese was likely to have evolved during the three centuries following the first publication of the Nogǒldae. The following extract shows some of the changes operated in comparison with the extract of the original text above:

blabla extract translation

The preface was not written by ___ but by

{ {INTRO PREFACE upcoming} }

A corresponding text with gloses, the Nogǒldae Sinsǒk Ǒnhae (老乞大新釋諺解, RR: Nogeoldae Sinseok Eonhae), was published in 1763 but appears to be no longer extant.

Original Script

| Text | Translation |

|---|---|

|

五方之民,言語不通,先王設四官以通其不通:東曰寄,西曰鞮,南曰象,北曰譯。類皆察其風氣之高下,齒舌之缓急,適乎時而便於俗而已。天下之生久矣,言語之随方燮易、與時同,固如水之益下,况中州之與外國,其齟齬不合,差毫釐而謬千里者,尤不腾其月異而歲不同矣。然我國之於中州,地之相去不過二千餘里,視閩、浙、雲,貴之人能喋喋通话於幽燕,大同而小異,我國則雖老譯,舉皆舌本閒強,話頭拙澀,鄒孟氏荘嶽眾楚之訓,真善諭也。我古置質正官,每歲以辨質華語為任,故東人之於華語,較之他外國最稱嫻習 。百年之閒(間),兹事發而譯學遂壞焉。 《老乞大》不知何時所創,而原其所錄,亦甚草草,且久而變焉,則其不中用無怪矣。譯於燕者,不過依俙倣想而行之,誠不可以膠柱而鼓瑟。舊時多名譯,周通爽利,聞一知二,不至逕庭。挽(晚)近以来,習俗解弛,濫竽者亦多,殆無以應對於兩國之間,識者憂之。余嘗言不可不大家釐正,上可之。及庚辰,銜命赴燕,遂以命賤臣焉。時譯士邊憲在行,以善華語名,賤臣請專屬於憲。及至燕館,逐條改證,别其同異,務令適乎時、便於俗,而古本亦不可删没,故併錄之,蓋存羊之意也。書成,名之日《老乞大新釋》,承上命也。既又以《朴通事新釋》分屬金昌柞之意筵稟,蒙允。自此諸書并有新釋,可以無礙於通話也。今此新釋,以便於通話為主,故往往有舊用正音而今反從俗者,亦不得已也。欲辨正音,則有《洪武正韻》《四聲通解》諸書在,可以考据,此亦不可不知也。在館見南掌國人(即古越裳氏)因雲南人其語,蓋重譯也,雖侏儺吞吐,有不可了,而然能畢通其情物。信乎,象譯之有關於王制也!仍記余丁卯赴日本,南譯之鹵莽,殆有甚於北,故遂改編《捷解新語》,以辨其古今之判殊,諸譯便之。日本有雨森東者,能通三國語,其弟子亦多能之者。夫以我國文辨聰俐之俗,苟有志於音訓之學,亦何難於曲暢而傍通哉!引而伸之,觸類而長之,天下言語之能事畢矣。諸譯豈有意哉?勉之哉!

|

The people from the five regions[1] differ in words and languages. The former kings established four officials by which what was differing was connected; in the east they were called ‘ji’, in the west they were called ‘xie’, in the south they were called ‘xiang’, in the north they were called ‘yi’[2]. They were examining the superiority and inferiority of the common practices/the levels of the breathing, the tensions of the teeth and the tongue, [they] were doing nothing more than following the times and adapting to the customs. The world was born a long time ago[3]; the words and languages found places and are object to variation, from time to time/with the times they are equivalent. Originally, like under the benefits/the flowing (down) of water[4], it went/spread out from the Central provinces[5] to the foreign countries; the irregularities of the [speakers’] teeth are not matching, and what differs from even a hair can yet lead you a thousand li astray [6], they greatly/the faults are unequal to them/it; the moon is not the same and the years are different[7]. If one goes from our country to the Central provinces, the mutual distance between these lands does not go beyond than 2000 li. We observe that the people of Min, Zhe, Yun and Gui[8] can chatter a lot and communicate in the Youyan[9]; [their speeches] have great similarities and small differences. Only our country needs experienced interpreters; They all raise the back of the tongue [letting it] idle or [moving it] with force, the thread of their speech is clumsy and obscure. The instruction of Mencius ?????? is a truly good teaching. We, in the past/used to, established the substance/nature and straightened the organs by which, every year, we would have the assignment of differentiating the substance/nature of the Chinese language (or it is talking about making people participate to examinations?). Therefore, the Chinese language of the people of the East[10] is the most praised and refined compared to the one of others foreign countries. Within a hundred years, this happened but the discipline of translating is eventually becoming bad. We do not know when the Nogôldae was created nor the one who recorded it; it was also [written a] very careless [way]. Moreover, it has been a while [since then] and there has been changes [in the language]! Therefore, no wonder why it is not used. As for those who do interpretation in Beijing, they proceed only by relying on vague imitations and considerations; it is truly not possible to play the se zither with the pegs glued[11]. In the former times there were many renown interpreters; [among them] Zhou Tong[12] was efficient and able, he knew twice when hearing once, he did not [make his translations] so different [from the original language]. Since recently, the usual practices got lost; those who get in [this position] without any qualification are also numerous; there is almost nobody that would be conform to being [working] between the two countries and those who are assigned [this task] are anxious about it. I once said that we cannot not rectify everyone [of them]; his highness agreed. I once said that we cannot not rectify everyone [that does translations]; his highness agreed. In the year gengcheng13, an order was carried out to go to Beijing and so [I] your minister followed it. At the time, the literati interpreter Pyôn Hôn[13] was an expert and he was renown because of his good Chinese; [I] your minister would only ask for his services. When we arrived in the Beijing embassy, he corrected [the sentences] point by point, classified with no difficulty [their] similarities and differences. He engaged in his assignment, followed the times/was on time and adapted to the customs. And since he could not erase the original text, he combined [it to new contents] and record [new sentences]; it was be the intention of the essence [of the book]. The book has been completed and we/he gave it the title New Edition of the Old Cathayan as we received his highness’ order. And [his highness] accepted that we classify Kim Ch’angjo’s[14] intentions by the means of the New Edition of the Park Interpreter[15]. After this, he/we annotated the book and obtained a new edition that does not affect communication. The present new edition gives priority to adapting to communication. Consequently, there often are ones who used to use standard pronunciations and those who now follow the customs have no other alternative. If one desires to identify the standard pronunciations, the books The Correct Rimes of Hong Wu[16] and the A Thorough Explanation of the Four Tones[17] are extant; it is possible to conduct textual research through them. This is also something that one cannot not be aware of. In the embassy I met people from Lan Xang[18] who were speaking by the mean of the language of Yunnan people; they were probably retranslating. Although they are short, ???, clear their throat and spit, there are [things] that they cannot [say], they however can manage to express the sentiments and things [that they want to express]. Would you believe it?/Really, Their interpreters have a link with/have a monarchy! If I may continue to write: I went to Japan in [the year] dingmao[19] The roughness and clumsiness of the interpreters of the south was almost worse than in the north, thus I revised [the book] A Quick Interpretation of the New Language[20]. In order to distinguish the differences between now and the past, I translated it all by taking [the differences] into account. In Japan there was someone whose name is Amenomori Hōshū[21] and who could communicate in three languages. His younger brother had also a lot of ability at it. As for the custom of good comprehension and intelligence by distinguishing our country’s writings, if one has an aspiration for the study of the ûm and hun[22], how would it be difficult [for him] to make sense[23]? Stretch and extend them, converge by categories and prolong them, and all possible things under heaver are accomplished[24]. How come there are all [kinds of] meanings? I shall exert myself at it! Written solemnly the 37th year xinsi[25] of his highness, the last third[26] of the 8th month by Hong Kyehui[27], High Senior Official de rang inférieur?, Second Great Composer of the ______ Office of the Composers of the Great State Council standing on the left side. |

- Discussion Questions:

References

Lung, Rachel (2011). “Perceptions of translating/interpreting in first-century China” in Setton, Robin. Interpreting Chinese, Interpreting China. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Compagny, pp. 11-28

Footnotes

- ↑ Or the “five directions”, that is the north, the south, the east, the west and the center.

- ↑ According to Lung (2011:13), Ji (寄), Di (鞋), Xiang (象) and Yi (譯) are different words denoting translators and interpreters (only the latter would have kept that meaning); this passage is also a reference to the chapter “Royal Institutions” (王制, pinyin: Wangzhi) in the Book of Rites (禮記, pinyin: Liji).

- ↑ This sentence was also borrowed from a Confucian classic, more precisely from the section entitled “Teng Wen Gong” (滕文公下) of the Works of Mencius (孟子, pinyin: Mengzi).

- ↑ This expression is quoted a few years later in the Journal of the Royal Secretariat (承政院日記, RR: Seungjeongwon Ilgi, MR: Sûngjôngwon Ilgi), in the 28th day of the 10th month of the 7th year of the reign of King Sunjo (r. 1800-1834), that is in 1807.

- ↑ This term refers to China.

- ↑ Periphrasis of the sentence “差以豪氂,謬以千里” in the “Biography of Sima Qian” (司馬遷傳, pinyin: Sima Qian Zhuan) in the Book of Han (漢書, pinyin: Han Shu).

- ↑ The formula “月異而歲不同矣” was borrowed from either the Xin Shu (新書) or the later written Book of Han.

- ↑ Min (閩) is an old appellation of the Chinese Fujian (福建) province while Zhe (浙), Yun (雲) and Gui (貴) respectively refer to the provinces of Zhejiang (浙江), Yunnan (雲南) and Guizhou (貴州).

- ↑ Youyan (幽燕) is an ancient region comprising Beijing and parts of modern Hebei and Liaoning provinces, in the North East of China

- ↑ Dongin (東人, MR: Tongin) is one of the ways the Koreans would designate themselves.

- ↑ This means they may not stubbornly stick to old ways in the face of changed circumstances; it was probably directly borrowed from the Shiji (史記).

- ↑ I was not able to find out who that was. It is also possible that this is not a proper noun.

- ↑ Pyôn Hôn (邊憲; RR: Byeon Heon; 1707~?) was one of the author of this revised textbook.

- ↑ Kim Ch’angjo (金昌祚; RR: Gim Changjo; ), the author of the New Edition of the Pak Interpreter

- ↑ Pak T’ongsa Sinsôk (朴通事新釋; RR: Bak T’ongsa Sinsôk): a revised edition of the Pak T’ongsa (朴通事; RR: Bak T’ongsa; early 15th century) from 1765

- ↑ The Correct Rimes of Hong Wu' (洪武正韻, pinyin: Hong Wu Zhengyun), a reference dictionary of rimes that was published in China in 1455.

- ↑ 'A Thorough Explanation of the Four Tones (四聲通解, MR: Sasông T’onghae, RR: Saseong Tonghae), an other dictionary of rimes for Chinese written by Ch’oe Sejin (崔世珍, RR, Choe Sejin) and published in 1517

- ↑ Lan Xang (Lao: ລ້ານຊ້າງຮົ່ມຂາວ) was a unified kingdom that existed from 1354 to 1707. Its territory had spread over parts of now’s Laos, Vietnam, China, Thailand, Myanmar and Cambodia

- ↑ Fourth year D-4 of the 60 year cycle, that is the year ____ in this text.

- ↑ A Quick Interpretation of the New Language (捷解新語, MR: Ch’ôp’aesinô, RR: Jeopaesineo) is textbook to learn Japanese that was published in 1676 by Kang Wusông (康遇聖, RR: Gang Wuseong).

- ↑ Amenomori Hōshū (あめのもり ほうしゅう; 1668-1755) was a Japanese scholar of Zhu Xi's neo-Confucian school.

- ↑ Ûm (音, RR: eum, pinyin: yin) and hun (訓, RR: hun, pinyin: xun) are respectively the pronunciation of sinographs and their meaning in the vernacular language of non-sinophones.

- ↑ The idiom “kokch’ang pangt’ong” (曲暢旁通, RR: gokchang bangtong, pinyin: quchang pangtong) is also found in other Chinese and Korean texts although I do not know where it first came from.

- ↑ This sentence is first used in the Book of Changes (, Yijing) to talk about “the Eight Trigrams constituting a small completion”; it borrowed expressions from the Book of the Later Han (後漢書, pinyin: Hou Han Shu; fifth century) which itself probably also found partly its inspiration in the Huainanzi (淮南子; second century BCE)

- ↑ Eighteenth year H-6 of the 60 year cycle, that is the year _____ in this text.

- ↑ Each month could be divided in periods of 10 days.

- ↑ Hong Kyehui (洪啓禧, RR: Hong Gyehui; 1703-1771)