"(Translation) 1614年 寺奴 斗(伊+叱)間 奴婢賣買明文"의 두 판 사이의 차이

| 1번째 줄: | 1번째 줄: | ||

{{Primary Source Document3 | {{Primary Source Document3 | ||

| − | |Image = | + | |Image = 1614년사노두잇노비매매명문1.JPG |

|English = A Document of trading a slave with a horse | |English = A Document of trading a slave with a horse | ||

|Chinese = 1614年 寺奴 斗(伊+叱)間 奴婢賣買明文 | |Chinese = 1614年 寺奴 斗(伊+叱)間 奴婢賣買明文 | ||

2017년 7월 20일 (목) 19:18 판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | A Document of trading a slave with a horse | |

| Chinese | 1614年 寺奴 斗(伊+叱)間 奴婢賣買明文 | |

| Korean(RR) | 1614년 사노 뒷간 노비매매명문 | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Social Life and Economic Strategies | |

| Type | Record | |

| Author(s) | 尹思誨 妻 金氏 | |

| Year | 1614 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | Trading | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2017 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | ||

| Year | 2017 | |

목차

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Original Script

- 3 Discussion Questions

- 4 Further Readings

- 5 References

- 6 Translation

- 6.1 Student 1 : (Write your name)

- 6.2 Student 2 : (Write your name)

- 6.3 Student 3 : (Write your name)

- 6.4 Student 4 : (Write your name)

- 6.5 Student 5 : (Write your name)

- 6.6 Student 6 : (Write your name)

- 6.7 Student 7 : King Kwong Wong

- 6.8 Student 8 : (Write your name)

- 6.9 Student 9 : (Write your name)

- 6.10 Student 10 : (Write your name)

- 6.11 Student 11 : (Write your name)

- 6.12 Student 12 : (Write your name)

- 6.13 Student 13 : (Write your name)

- 6.14 Student 14 : (Write your name)

- 7 Further Readings

Introduction

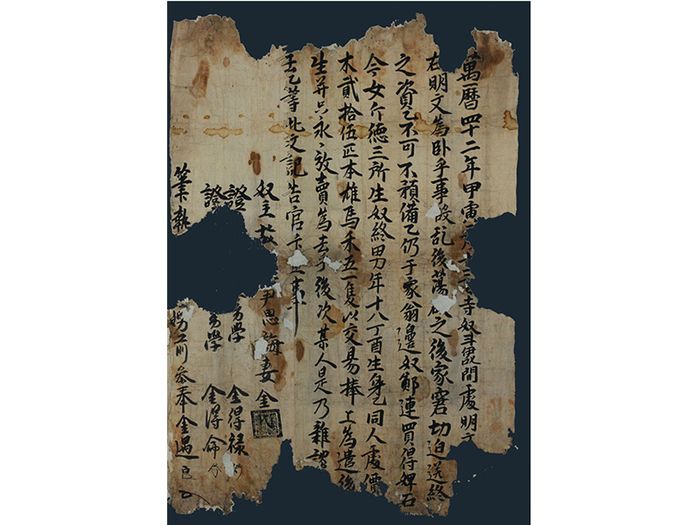

A Document of trading a slave with a horse is an old document of Joseon Korea obtained from Nogudang (the House of Green Rain Forest), the residence of the leading family of Haenam Yun clan in Jeollanamdo. Written in 1614, it is a contract of economic transaction between Mrs. Kim, a widow of a man named Yun Sahoe (who was not a member of Haenam Yun clan), and a male slave named Privy. Mrs. Kim, on account of her family's reduced circumstances after the war (Imjin waeran) and her husband's death, sells an eighteen-year-old male slave Jongnam to Privy in exchange for a five-year-old male horse worth twenty-five bulks of cotton.

In the document, Privy is referred to as 寺奴. While the term is usually pronounced as "sino" and means a capital bureau slave in Joseon Korea, in this particular instance it may refer to a slave working for a Buddhist temple. In such case the word is pronounced "sano" (literally meaning temple slave). It is most likely that Privy was a slave belonging to Daeheungsa (a.k.a. Daedunsa), a Buddhist temple in Haenam County near Nogudang which maintained a close relationship with Haenam Yun clan, where this document was preserved. Therefore, it is certain that the slave Privy was not buying a slave for himself, but only working as a legal agent for Daeheungsa. It was a common practice for the Yangban families and corporate institutions such as Buddhist temples and Confucian academies to have their slaves work as legal agents and sign economic contrasts in their stead.

This knowledge is necessary to fully understand the content of this economic contract. The contract states that Mrs. Kim is selling the slave Jongnam, whose is a grandson of a female slave Seokgeum. The contract also states that Seokgeum was bought by Mrs. Kim's late husband's slave Jeomryeon. This opens up two possible interpretations: either Jeomryeon had bought Seokgeum as his own property, or Jeomryeon was working as a legal agent for Mrs. Kim's late husband. But the first possibility is untenable. If Seokgeum was Jeomryeon's property then Seokgeum's grandson would also have been Jeomryeon's property (the slave status was inherited to the next generation), so Mrs. Kim would not have the right to sell off Seokgeum's grandson Jongnam. Therefore, it is only reasonable to think that Jeomryeon was acting as a legal agent to Mrs. Kim's late husband, who was the actual buyer of Seokgeum.

But this does not mean that slaves could not buy slaves for themselves. In fact, in the Joseon society there were slaves who amassed wealth and engaged in economic transactions such as buying and selling land, slaves, etc. Acquisition of wealth and ownership of private property was especially prominent among tribute-paying slaves (napgong nobi), whose obligation to the master was limited to paying taxes and did not include providing service or labor. For this reason, when reading economic contracts of Joseon Korea, it is important to discern the case of a slave acting as his own representative and the case of a slave acting as a legal agent for the master.

This document stands out from other old contracts of economic transaction in that all the appendixes attached by the county office to the original contract are, save for some minor tear and damage, preserved in tact. There are three appendixes in total. Appendix One, A Statement of trading a slave with a horse, is an official record of the testimony made by Mrs. Kim at the county office verifying the fact that she indeed sold the male slave Jongnam to the temple slave Privy in exchange for a horse. Appendix Two, Kim Deukrok's Statement of trading a slave with a horse, is a testimony made by the three witnesses including a man named Kim Deukrok to this economic transaction. In order for an economic contract such as this one to be notarized by the county office, all pertaining individuals (seller, buyer, and witnesses) had to be present at the office and make their oral testimonies, which the scribe wrote down for record-keeping. But noteworthy is the fact that Mrs. Kim also chose to be present at the office and give oral testimony, instead of sending her testimony in the form of a letter as many women did at the time. The third and last appendix is A Certificate of trading a slave with a horse issued by the county office notarizing this economic transaction. The certificate explains each step of the verification process taken by the county office: collecting and comparing all the testimonies, and looking up the slave register to confirm the fact that a slave named Seokgeum was indeed bought by the slave Jeomryeon. Together with the appendixes, this contract shows a highly developed bureaucratic and administrative system in Joseon Korea.

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

萬曆四十二年甲寅〔三〕月〔十三〕日寺奴斗{伊+叱}間處明文

右明文爲臥乎事段亂後蕩破之後家窘切迫送終 之資乙不可不預備乙仍于家翁邊奴鄭連買得婢石 今女斤德三所生奴終男年十八丁酉生身乙同人處價▣ 木貳拾伍匹本雄馬禾五一隻以交易捧上爲遣後〔所〕 生幷只永永放賣爲去乎後次某人是乃雜談〔有〕 去乙等此文記告官卞正事 奴主故〔幼學〕尹思誨妻金氏[圖署] 證▣…▣幼學金得祿[着名] 證▣…▣幼學金得命[着名] 筆執▣…▣娚前參奉金遇[着名][署押] |

First Part (by Jong Woo): The forty-second year of Wanli (1614), (third) month, (thirteenth) day.The document to Twitkkan, a public slave. As to what this documents pertains, the reason [for the transaction] is that, in the aftermath of the war, my house has been impoverished to the point of having no money for the funeral and I cannot loan [money] from other people. Middle Part (by Kim Young): I exchange the eighteen-year-old male slave Jongnam born in Jeongyu year--the son of a female slave Geundeok who is the daughter of a female slave Seokgeum whom my late husband's male slave Jeongryeon had bought [in his stead]--with a five-year-old male horse that is worth twenty-five bulks of cotton. All offspring [of Jongnam] hereafter... Ending Part (by Martin Gehlmann): …are also sold permanently. If at a later time someone or so should have a dispute, [take] this document and report to the authorities for justice to this matter. Slave master, deceased [scholar-in-training] Yun Sahoe’s Wife Mrs. Kim [Stamped] Witness, scholar-in-training Kim Deukrok [Signature] Witness, scholar-in-training Kim Deukmyeong [Signature] Scribe, ?? Tomb Guardian Kim U [Signature] [Stamped]

|

Discussion Questions

Further Readings

- 정윤섭, 녹우당 綠雨堂: 해남윤씨 댁의 역사와 문화예술, 열화당, 2015.

References

Translation

Student 1 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 2 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 3 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 4 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 5 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 6 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 7 : King Kwong Wong

- Discussion Questions:

Since the document was signed by Madame Kim and witnessed by (possibly) her relatives, would this the case that Madame Kim managed her husband's family property as the widow of the deceased Yun Sahoe?

Student 8 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 9 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 10 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 11 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 12 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 13 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions:

Student 14 : (Write your name)

- Discussion Questions: