"(Translation) 御製戒酒綸音"의 두 판 사이의 차이

(→Chinese Script) |

|||

| (사용자 2명의 중간 판 5개는 보이지 않습니다) | |||

| 17번째 줄: | 17번째 줄: | ||

=='''Introduction by Youngsuk Park'''== | =='''Introduction by Youngsuk Park'''== | ||

| − | King Yŏngjo's Prohibition of Wine Drinking | + | King Yŏngjo's Yunūm: Prohibition of Wine Drinking |

| − | The King Yŏngjo's Prohibition of Wine Drinking was published in 1757 (the 33rd year of King Yŏngjo's reign). King Yŏngjo (r. 1724-1776) was the twenty-first ruler of Chosŏn dynasty (1392-1910). This volume consists of eighteen leaves printed by the wood block carvings and written in classical Chinese phrases with the addition of Korean interpretation and endings. It is the record of King Yŏngjo's Words of Edification (yunūm) for the people. Yunūm was directly composed by the king himself and its audience varies depending on the purpose from the high ministers and bureaucrats down to commoners. The king himself often spoke spontaneously and his Royal Secretariat dictated his speech including his emotional expressions and exclamations. This Prohibition of Wine Drinking was written during the king's prime time obtaining stability of political power right after suppressing the purge (1755). In his latter period of ruling King | + | The King Yŏngjo's Prohibition of Wine Drinking was published in 1757 (the 33rd year of King Yŏngjo's reign). King Yŏngjo (r. 1724-1776) was the twenty-first ruler of Chosŏn dynasty (1392-1910). This volume consists of eighteen leaves printed by the wood block carvings and written in classical Chinese phrases with the addition of Korean interpretation and endings. It is the record of King Yŏngjo's Words of Edification (yunūm) for the people. Yunūm was directly composed by the king himself and its audience varies depending on the purpose from the high ministers and bureaucrats down to commoners. The king himself often spoke spontaneously and his Royal Secretariat dictated his speech including his emotional expressions and exclamations. This Prohibition of Wine Drinking was written during the king's prime time obtaining stability of political power right after suppressing the purge (1755). In his latter period of ruling King Yŏngjo produced a number of yunūm documents, whose themes and audience were not at all monotonous but rather complex and various. Among those in which King Yŏngjo showed his particular concerns by repeatedly proclaiming are topics on Harmonizing in impartiality and Parity of corvee labor. They are mentioned in "In King Yŏngjo's own writing, When Asked of My Enterprises"<ref>"御製問業” in 《英祖大王》 (藏書閣, 2011) Vol. 15: 140-141.</ref> Thriftiness was also one of the steadily pursued subjects, for which the king proclaimed the prohibition of luxury for commoners on one hand, and edified the court members that it was the palace first to defy luxurious lifestyle and practice thriftiness on another hand. The Prohibition of wine drinking is directly related to this edification of thriftiness. Although the king sent out messages concerning drinking problem before, he adamantly enforced the prohibition due to the incident that he himself succumbed to drinking and caused a great commotion. It was right after the purge of his political opponents the king perhaps was emotionally overwhelmed and lost control of himself. In this document of the Prohibition of Wine Drinking the king expresses resentment of his own fault, which led the nation to lose the control with drinking and even in danger of collapsing, he feared. Deeply saddened, he implores ancestral spirits in tears in the Hall of Portraits to assist him with his capacity to persuade people to restrain from drinking. He confesses that he himself is the grave sinner who caused the increasing number of violaters which reached now over a thousand. He instructs people how insidiously harmful drinking habit could be for one's life and becomes relentless about enforcing the prohibition law. His decision thus came to exclude the drinking violaters from the great amnesty. |

| − | This book written in both classic Chinese and additional ŏnmun (諺文, vernacular writing) is a good example of the publishing activities during the period known as the renaissance in literature in the late eighteenth century | + | This book written in both classic Chinese and additional ŏnmun (諺文, vernacular writing) is a good example of the publishing activities during the period known as the renaissance in literature in the late eighteenth century. During this period King Yŏngjo and his successor King Chŏngjo (1776-1800) promoted the publication of books written in vernacular writing. As the result, more than thirty books in ŏnmun were published testifying the existence of a broad common audience who read in Korean. Korean language since being invented by King Sejong in the fifteenth century became pervasive in the Chosŏn society by the eighteenth century. |

| + | [1] "御製問業” in 《英祖大王》 (藏書閣, 2011) Vol. 15: 140-141. | ||

| 189번째 줄: | 190번째 줄: | ||

11. 必也罄心誨諭, 流涕勉飭, 使我苦心, 能行於國中, 而使我元元, 罔陷於大戾, 非徒邦國之, 幸於羣工亦豈無陰功乎! 其莫曰臺上庭下只有其君與臣, 陟降洋洋彼蒼昭昭, 可不懼哉! 可不懍哉! 其各明聽欽遵予諭! | 11. 必也罄心誨諭, 流涕勉飭, 使我苦心, 能行於國中, 而使我元元, 罔陷於大戾, 非徒邦國之, 幸於羣工亦豈無陰功乎! 其莫曰臺上庭下只有其君與臣, 陟降洋洋彼蒼昭昭, 可不懼哉! 可不懍哉! 其各明聽欽遵予諭! | ||

| + | |||

| 238번째 줄: | 240번째 줄: | ||

(1) The quotation is from the historical books of Han dynasty – Dong Guan Han Ji and Huo Han Shu (東觀漢記, 傳七, 馬廖; 後漢書, 列傳, 馬援列傳). | (1) The quotation is from the historical books of Han dynasty – Dong Guan Han Ji and Huo Han Shu (東觀漢記, 傳七, 馬廖; 後漢書, 列傳, 馬援列傳). | ||

| + | |||

(2) Chenghao (程顥, 1032-1085) was a neo-Confucian philosopher in the Song dynasty. He was addicted to hunting when he was young, but he abstained the habit after he devoted himself to study. However, it is said that he still felt itching when he saw others hunting even after 12 years. See: 《二程遗书》卷七:“猎,自谓今无此好。周茂叔曰:‘何言之易也,但此心潜隐未发,一日萌动,复如前矣。’后十二年。因见,果知未。”注云:“明道(即程颢)年十六七时,好田猎。十二年,暮归,在田野间见田猎者,不觉有喜心。” | (2) Chenghao (程顥, 1032-1085) was a neo-Confucian philosopher in the Song dynasty. He was addicted to hunting when he was young, but he abstained the habit after he devoted himself to study. However, it is said that he still felt itching when he saw others hunting even after 12 years. See: 《二程遗书》卷七:“猎,自谓今无此好。周茂叔曰:‘何言之易也,但此心潜隐未发,一日萌动,复如前矣。’后十二年。因见,果知未。”注云:“明道(即程颢)年十六七时,好田猎。十二年,暮归,在田野间见田猎者,不觉有喜心。” | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 508번째 줄: | 511번째 줄: | ||

=='''Further Readings'''== | =='''Further Readings'''== | ||

| − | + | ||

<div style="color:#008080;"> | <div style="color:#008080;"> | ||

* View together with '''[[Record of Property Distribution among Brothers from 1621]]'''. | * View together with '''[[Record of Property Distribution among Brothers from 1621]]'''. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | -- | + | <!-- |

| + | |||

* | * | ||

* | * | ||

| 717번째 줄: | 721번째 줄: | ||

* View together with '''[[정조 윤음 번역|(Translation) King Jeongjo, “Royal dictum to encourage farming” (Gweonnong yuneum 勸農綸音, 1781)]]''' | * View together with '''[[정조 윤음 번역|(Translation) King Jeongjo, “Royal dictum to encourage farming” (Gweonnong yuneum 勸農綸音, 1781)]]''' | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | --> | ||

2022년 2월 14일 (월) 23:45 기준 최신판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | King Yeongjo’s Prohibition of Wine Drinking | |

| Chinese | 御製戒酒綸音 | |

| Korean(RR) | 어제계주윤음(어졔계쥬륜음) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Royal Documents | |

| Type | [[ ]] | |

| Author(s) | King Yeongjo | |

| Year | 1757 | |

| Source | ||

| Key Concepts | King Yeongjo, | |

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2017 Summer Hanmun Workshop (Advanced Translation Group) | |

| Editor(s) | ||

| Year | 2017 | |

목차

Introduction by Youngsuk Park

King Yŏngjo's Yunūm: Prohibition of Wine Drinking

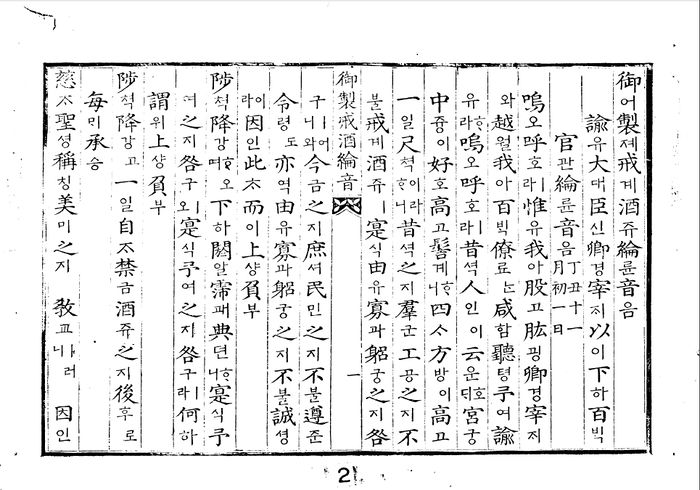

The King Yŏngjo's Prohibition of Wine Drinking was published in 1757 (the 33rd year of King Yŏngjo's reign). King Yŏngjo (r. 1724-1776) was the twenty-first ruler of Chosŏn dynasty (1392-1910). This volume consists of eighteen leaves printed by the wood block carvings and written in classical Chinese phrases with the addition of Korean interpretation and endings. It is the record of King Yŏngjo's Words of Edification (yunūm) for the people. Yunūm was directly composed by the king himself and its audience varies depending on the purpose from the high ministers and bureaucrats down to commoners. The king himself often spoke spontaneously and his Royal Secretariat dictated his speech including his emotional expressions and exclamations. This Prohibition of Wine Drinking was written during the king's prime time obtaining stability of political power right after suppressing the purge (1755). In his latter period of ruling King Yŏngjo produced a number of yunūm documents, whose themes and audience were not at all monotonous but rather complex and various. Among those in which King Yŏngjo showed his particular concerns by repeatedly proclaiming are topics on Harmonizing in impartiality and Parity of corvee labor. They are mentioned in "In King Yŏngjo's own writing, When Asked of My Enterprises"[1] Thriftiness was also one of the steadily pursued subjects, for which the king proclaimed the prohibition of luxury for commoners on one hand, and edified the court members that it was the palace first to defy luxurious lifestyle and practice thriftiness on another hand. The Prohibition of wine drinking is directly related to this edification of thriftiness. Although the king sent out messages concerning drinking problem before, he adamantly enforced the prohibition due to the incident that he himself succumbed to drinking and caused a great commotion. It was right after the purge of his political opponents the king perhaps was emotionally overwhelmed and lost control of himself. In this document of the Prohibition of Wine Drinking the king expresses resentment of his own fault, which led the nation to lose the control with drinking and even in danger of collapsing, he feared. Deeply saddened, he implores ancestral spirits in tears in the Hall of Portraits to assist him with his capacity to persuade people to restrain from drinking. He confesses that he himself is the grave sinner who caused the increasing number of violaters which reached now over a thousand. He instructs people how insidiously harmful drinking habit could be for one's life and becomes relentless about enforcing the prohibition law. His decision thus came to exclude the drinking violaters from the great amnesty.

This book written in both classic Chinese and additional ŏnmun (諺文, vernacular writing) is a good example of the publishing activities during the period known as the renaissance in literature in the late eighteenth century. During this period King Yŏngjo and his successor King Chŏngjo (1776-1800) promoted the publication of books written in vernacular writing. As the result, more than thirty books in ŏnmun were published testifying the existence of a broad common audience who read in Korean. Korean language since being invented by King Sejong in the fifteenth century became pervasive in the Chosŏn society by the eighteenth century.

[1] "御製問業” in 《英祖大王》 (藏書閣, 2011) Vol. 15: 140-141.

- Download : 御製戒酒綸音.pdf

Original Script

嗚오呼호[ㅣ라]惟유我아股고肱굉卿경宰[와]越월我아百僚료[]咸함聽텽予여諭유[라]

嗚오呼호[ㅣ라]昔셕人인[이]云운[호]宮궁中즁[이]好호高고髻계[니]四方방[이]高고一일尺쳑[이라니]昔셕之지羣군工공之지不불戒계酒쥬[ㅣ]寔식由유寡과躬궁之지咎구[ㅣ어니와]今금之지庶셔民민之지不불遵준令령[도]亦역由유寡과躬궁之지不불誠셩[이라]

因인此而이上샹負부陟쳑降강[오며]下하閼알霈패典뎐[니]寔식予 여之지咎구[ㅣ오]寔식予여之지咎구[ㅣ라]何하謂위上샹負부陟쳑降강[고]一일自禁금酒쥬之지後후[로] 每承승慈聖셩稱칭美미之지 敎교[ㅣ러니]

因인山산纔訖흘[고]今금歲셰不불盡진[야셔]而이非비徒도不불止지[라]甚심至지會회飮음[니]陟쳑降강[이]有유知지[시면]其기以이寡과躬궁[으로]爲위能능禁금乎호[아]否부乎호[아]此[ㅣ]所소謂위上샹負부陟쳑降강也야[ㅣ오]何하謂위下하閼알霈패典뎐[고]

噫희[라]今금春츈霈패典뎐[은]往왕牒텹所소無무[ㅣ로]而이至지於어犯범酒쥬者쟈[야]恐공或혹弛시禁금[야]一일竝병不불赦샤[ㅣ러니]今금因인處쳐分분而이取츄覽람徒도流류案안[니]則즉其기數수[ㅣ]將쟝近근十십百[이라]若약此不불已이[면]將쟝不불知지至지於어幾긔十십百[이니]此[]卽즉予여[ㅣ]不불敎교而이令령民민陷함法법也야[ㅣ라]

思之지及급此[애]不불覺각懍름然연[호라]幾긔百徒도流류[]於어春츈大대赦샤[애도]不불能능放방焉언[니]是시豈긔同동慶경之지意의[며]而이今금[애]雖슈一일倂병放방釋셕[이나]何하與여於어赦샤典뎐哉[리오]

此[ㅣ]所소謂위下하閼알霈패典뎐也야[ㅣ라]其기將쟝何하顔안[으로]行朔삭 祭졔於어孝효昭쇼殿뎐[이며]亦역將쟝何하顔안[으로]曉효拜眞진殿뎐乎호[아]噫희[라]酒쥬[]乃내尤우物물也야[ㅣ니]今금番번宣션諭유[애]小쇼民민之지感감動동[을]其기何하必필哉[리오]且챠頃경者쟈宣션諭유[]只지於어父부老로[고]不불及급公공卿경[니]此豈긔董동子所소云운正졍朝죠廷뎡而이正졍萬만民민之지義의乎호[아]

其기君군其기臣신之지相샹與여戒계酒쥬[ㅣ]視시小쇼民민[애]雖슈有유切졀焉언[이나]以이程졍子之지大대賢현[으로도]猶유不불無무觀관獵렵之지悔회[시니]況황在凡범人인[애]尤우不불可가放방心심也야[ㅣ오]且챠以이尙샹書셔訓훈體톄[로]言언之지[라도]其기宜의竝병諭유臣신庶셔[]又우於어心심中즁[에]不불耐내憧츙憧츙[야]今금曉효祭졔畢필後후[에]仍잉泣읍奏주殿뎐中즁曰왈[오]

于우今금酒쥬禁금之지不불行[은]寔식由유一일人인[이니]一일人인[은]其기誰슈[오]卽즉臣신也야[ㅣ라]此後후[애]酒쥬若약復부行[이면]國국必필隨슈亡망[이니]不불戒계其기君군[은]雖슈無무足죡道도[ㅣ어니와]三삼百年년宗종社샤[ㅣ]豈긔可가由유一일人인而이亡망哉[잇가]臣신曁긔後후之지嗣王왕[이]或혹有유不불戒계酒쥬之지事[ㅣ면]則즉諸져臣신[이]雖슈不불知지[고]庶셔民민[이]雖슈亦역不불知지[나]於오昭쇼陟쳑降강[은]若약鑑감之지照죠[시리니]若약有유犯범焉언[이어든]

奏주于우列렬朝죠[샤]明명降강大대何하[시되]止지于우其기身신[시고]若약於어羣군臣신[애]或혹知지而이不불諫간[며]或혹身신犯범其기戒계者쟈[]亦역降강大대何하[샤]使我아海東동臣신庶셔[로]無무面면謾만之지態[케시며]諫간而이不불聽텽[이면]咎구亦역在君군[이니]臣신何하咎구焉언[이리잇고]

以이此口구奏주[고]仍잉坐좌月월臺[야]召쇼集집陪 祭졔宗종親친文문武무百官관於어殿뎐庭뎡[야]洞동諭유予여意의[노니]言언雖슈略약[이나]意의則즉盡진矣의[라]

噫희[라]上샹自股고肱굉[으로]下하至지百僚료[히]體톄予여爲위宗종社샤苦고心심[야]其기銘명其기佩패[야]莫막替톄予여意의[라]至지於어禁금酒쥬[야]小쇼民민之지犯범者쟈[]勿물以이摘젹得득爲위幸[이오]必필以이無무刑형爲위期긔[니]京경而이京경尹윤部부官관[과]外외而이方방伯守슈令령[이]凡범於어對民민也야[애]必필也야罄경心심誨회諭유[며]流류涕톄勉면飭칙[야]使我아苦고心심[으로]能능行於어國국中즁[며]而이使我아元원元원[으로]罔망陷함於어大대戾려[케면]非비徒도邦방國국之지幸[이라]

於어羣군工공[애]亦역豈긔無무陰음功공乎호[ㅣ리오]其기莫막曰왈臺上샹庭뎡 下하[애]只지有유其기君군與여臣신[이라라]陟쳑降강[이]洋양洋양[시고]彼피蒼창[이]昭쇼昭쇼[시니]可가不불懼구哉[며]可가不불懍름哉[아]其기各각明명聽텽[야]欽흠遵준予여諭유[라]

諭유京경城셩父부老로綸륜音음[丁丑十月二十五日]

嗚오呼호[ㅣ라]以이予여否부德턱[으로]忝텸守슈丕비基긔[ㅣ]于우今금三삼十십有유三삼年년[이로]而이上샹不불能능繼계述슐先션志지[고]下하不불能능惠혜究구蔀부屋옥[야]綱강紀긔[ㅣ]日일墜츄[며]生民민[이]日일窮궁[니]心심常샹懍름惕텩[야]若약隕운淵연谷곡[이라]近근尤우衰쇠耗모之지中즁[애]誠셩孝효[ㅣ]淺쳔薄박[야]仙션馭어[]莫막攀반[고]只지自號호慕모[야]萬만念렴俱구冷[니]其기於어政졍令령[애]何하能능振진刷솰[이리오]而이然연[이나] 禁금酒쥬之지令령[은]卽즉予여苦고心심[이라]

古고人인[이]云운[호]有유志지者쟈[ㅣ]事竟경成셩[이라고]傳젼[애]亦역云운[호]堯요舜슌[과]桀걸紂쥬[의]率슐天텬下하[애]民민皆從죵之지[라니]噫희[라]嗣服복之지初초[애]禁금借챠閭려家가而이士夫부[ㅣ]從죵焉언[고]晩만後후[애]禁금用용紋문緞단而이京경外외[ㅣ]從죵焉언[니]而이民민從죵之지之지義의[]於어此可가見견[이로]至지於어酒쥬禁금[야]今금已이二이載[로]其기猶유不불遵준[야]窮궁海之지中즁[애]編편配相샹續쇽[니]昔셕[애]益익[이]贊찬禹우曰왈[호]至지諴함[이]感감神신[이온]矧신玆有유苗묘[ㅣ녀야]帝뎨[ㅣ]乃내誕탄敷부文문德덕[샤]干간戚쳑兩량階[신대]有유苗묘[ㅣ]乃내格격[니]

噫희[라]至지愚우而이神신者쟈[ㅣ]民민也야[ㅣ라]寡과躬궁[이]若약能능誠셩心심禁금酒쥬[ㅣ면]民민豈긔不불從죵[이리오] 故고[로]夏하閒간[애]只지下하勸권諭유之지旨지[고]伊이後후[애]惟유付부有유司而이治치之지矣의[러니]初초冬동[이]將쟝盡진[고]經경歲셰不불遠원[이라]其기不불能능弛시心심[야]試시令령宣션傳젼官관[으로]廉렴察찰[니]

噫희[라]前젼日일甁병甖之지釀양[도]其기猶유寒한心심[이어든]方방當당遏알密밀之지時시[야]十십餘여人인之지聚츄飮음[은]非비徒도放방恣無무嚴엄[이라]酒쥬禁금之지蕩탕然연[을]於어此可가見견[이니]其기咎구[ㅣ]焉언在[오]寔식在寡과躬궁[이라]

噫희[라]臨림御어卅삽載[애]誠셩信신[이]若약孚부於어民민[이면]幺요麽마禁금令령[을]民민豈긔不불從죵[이리오]寔식予여之지咎구[ㅣ오]昔셕之지不불能능戒계酒쥬[]非비由유蕩탕心심[이라]寔식爲위寬관懷회[로]而이予여[ㅣ]旣긔不불戒계[니]則즉民민之지不불從죵[이]固고其기然연也야[ㅣ어니와]一일自命명禁금之지後후[로]酒쥬之지一일字[ㅣ]方방寸촌[애]已이無무[ㅣ로]而이民민犯범[이]若약此[]其기咎구[ㅣ]何하在[오]予여[ㅣ]不불能능信신法법於어下하[ㅣ라]故고小쇼民민[이]其기敢감揣度탁曰왈[호]禁금令령[이]雖슈嚴엄[이나]豈긔無무弛시張쟝之지日일乎호[아니]

此[ㅣ]寡과躬궁[의]恒日일不불誠셩之지致치[니]寔식予여之지咎구[ㅣ오]語어[애]云운[호]導도之지以이德덕[고]齊졔之지以이禮례[면]有유恥치且챠格격[이오]導도之지以이政졍[고]齊졔之지以이刑형[이면]民민免면而이無무恥치[라시니]今금予여[ㅣ]不불能능以이德덕導도之지[고]徒도欲욕以이刑형齊졔之지[니]民민豈긔從죵焉언[이리오]

寔식予여之지咎구[ㅣ오]其기君군[이]七칠十십服복衰최[야]方방在朝죠夕셕號호泣읍之지中즁[니]爲위其기民민者쟈[ㅣ]竊졀飮음[도]宜의不불敢감[이어든]況황羣군聚츄而이放방飮음乎호[아]此[]寡과躬궁之지誠셩孝효[ㅣ]淺쳔薄박[야]不불能능孚부感감而이然연[이니]寔식予여之지咎구[ㅣ오]雖슈非비禁금酒쥬之지時시[라도]會회飮음[이]本본自有유禁금令령[이어든]況황當당國국恤슐[야]若약是시狼랑藉쟈[호]而이法법司[ㅣ]無무異이聾롱瞽고[니]恒日일之지紀긔綱강[이]若약擧거[ㅣ면]則즉豈긔有유是시乎호[아]寔식予여之지咎구[ㅣ오]噫희[라]其기君군[이]誠셩心심斷단酒쥬[고]誠셩心심飭칙勵려[호]而이猶유不불能능止지[야]前젼後후被피配者쟈[ㅣ]殆近근十십百[니]犯범者쟈[]雖슈無무足죡道도[ㅣ나]其기望망海呼호號호之지妻쳐孥노[]何하辜고之지有유哉[오]恒日일之지敎교化화[ㅣ]能능行[야]民민自信신令령[이면]則즉豈긔若약是시乎호[ㅣ리오]寔식予여之지咎구[ㅣ오]

噫희[라]今금春츈赦샤典뎐[은]可가謂위無무前젼大대霈패[로]而이關관係계酒쥬禁금者쟈[앤]則즉一일不불赦샤焉인[은]惟유恐공禁금令령之지或혹弛시[러니]而이犯범者쟈[ㅣ]猶유不불絶졀[이라]霈패不불能능行[고]禁금亦역不불行[니]寔식予여之지咎구[ㅣ라]以이此推츄之지[니]一일則즉予여咎구[ㅣ오]二이則즉予여咎구[ㅣ라]玆乃내先션諭유寡과躬궁之지咎구[고]次陳진崇종飮음之지弊폐[노니]

噫희[라]范범質질所소云운狂광藥약非비佳가味미[ㅣ]可가謂위切졀至지[오]食식色[을]雖슈竝병稱칭[이나]而이食식慾욕之지中즁[애]酒쥬尤우甚심焉언[이오]謂위其기害해則즉反반甚심於어色[니]何하則즉[고]沈침湎면于우酒쥬[면]不불知지五오倫륜[니]其기害해[ㅣ]一일也야[ㅣ오]小쇼則즉鬪투鬨홍[며]

大대則즉殺살人인[니]其기害해[ㅣ]二이也야[ㅣ오]小쇼則즉喪상性셩[며]大대則즉隕운身신[니]其기害해[ㅣ]三삼也야[ㅣ라]觀관其기犯범者쟈[ㅣ]多다是시朝죠夕셕難난繼계[야]

以이此爲위生涯애者쟈[ㅣ니]其기情졍[이]雖슈若약可가矜긍[이나]而이麴국糱얼之지外외[예]亦역多다可가以이資生者쟈[ㅣ어든]何하拘구目목前젼之지小쇼利리[야]自陷함於어罔망赦샤之지重즁法법乎호[ㅣ리오]噫희[라]禁금令령[이]當당嚴엄

故고[로]雖슈不불容용貸[나]昔셕之지夏하禹우[ㅣ]其기亦역泣읍辜고[시니]彼피犯범禁금者쟈[ㅣ]卽즉予여赤젹子[ㅣ라]其기雖슈置치法법[이나]予여豈긔樂락爲위[리오]爾이等등之지犯범邦방憲헌慽쳑君군心심[은]是시誠셩何하心심[이며]是시誠셩何하心심[고]

噫희[라]予여雖슈否부德덕[이나]臨림御어幾긔年년[애]一일心심憧츙憧츙[이]惟유在元원元원[이언마]而이爾이等등[이]不불遵준君군令령[야]使白首슈望망七칠之지君군[으로]若약是시費비心심[니]予여[ㅣ]雖슈負부爾이等등[이나]爾이等등[이]亦역何하忍인負부予여[오]尤우爲위慨개然연者쟈[]頃경於어壬임申신冬동齊졔籲유時시[예]深심感감爾이等등之지誠셩[이러니]于우今금犯범令령[은]一일何하反반焉언[고]從죵此以이後후[로]爾이等등[이]雖슈曰왈不불忘망予여[ㅣ라도]予여何하信신然연[이며]亦역何하顔안[으로]南남面면對爾이乎호[ㅣ리오]

爾이等등[은]莫막曰왈犯범者쟈[ㅣ]是시蠢쥰蠢쥰愚우氓[이라라]人인之지異이於어禽금獸슈[]以이其기有유五오倫륜也야[ㅣ니]狗구馬마[도]猶유戀련主쥬[ㅣ어든]況황人인乎호哉[아]尤우可가恧뉵焉언者쟈[]予여[ㅣ]若약有유誠셩[이어나]予여[ㅣ]若약有유德덕[이면]使列렬朝죠愛恤슐之지元원元원[으로]一일何하至지此哉[리오]思之지及급此[애]誠셩無무對爾이之지面면[이로니]尤우何하有유他타日일歸귀拜之지顔안[이리오]

呼호寫샤到도此[애]聲셩隨슈淚류下하[노니]爾이等등[인]亦역豈긔不불感감動동乎호[ㅣ리오]噫희[라]亦역莫막曰왈禁금令령之지或혹弛시[라라]乾건坤곤[이]雖슈混혼沌돈[이라도]此禁금[은]決결不불解[리니]吁후嗟차此禁금[은]當당與여國국偕存존[이오]當당與여國국偕亡망[리라]

噫희[라]廟묘社샤[애]用용醴례酒쥬[고]而이旨지酒쥬[ㅣ]若약行[이면]予여[ㅣ]雖슈欲욕赦샤[나ㅣ] 陟쳑降강[이]必필不불赦샤[시며]

陟쳑降강[이]雖슈欲욕赦샤[시나]神신祇기[ㅣ]決결不불赦샤[리니]旣긔知지三삼不불赦샤[고]甘감心심犯범憲헌[은]抑억何하心심哉[며]抑억何하心심哉[오]以이此言언之지[면]時시君군[이]雖슈欲욕解禁금[이나]何하敢감違위神신祇기陟쳑降강之지禁금乎호[ㅣ리오]

噫희[라]此[ㅣ] 非비恐공動동而이諭유者쟈[ㅣ오]卽즉實실理리也야[ㅣ라] 噫희[라]此則즉特특諭유其기大대者쟈[ㅣ어니와]抑억論론其기次[리니] 予여[ㅣ]雖슈否부德덕[이나]君군臨림爾이等등[야]鬚슈髮발[이]俱구白[니]比비之지恒人인[컨대]子弟뎨僮동僕복[이]不불遵준白髮발父부兄형與여其기主쥬之지令령[이면]其기可가曰왈爲위子弟뎨[며]爲위僮동僕복乎호[아]靜졍攝셥之지中즁[애]聞문此會회飮음之지說셜[고]心심不불能능耐내[야]不불憚탄其기勞로[고]半반夜야綴쳘文문[야]待朝죠召쇼諭유[고]令령京경兆죠[로]眞진諺언謄등書셔[야]曉효諭유京경外외[노라]吁후嗟차此酒쥬[]今금日일[애]益익覺각其기爲위尤우物물[이로니]

噫희[라]此尤우物물[이]止지息식然연後후[에야]食식可가甘감而이寢침可가便편[이니]

嗚오呼호[ㅣ라]小쇼大대民민人인[은]咸함聽텽此諭유[야]各각須슈自勵려焉언[라] 噫희[라]今금日일召쇼諭유之지後후[]卽즉予여一일初초政졍也야 [ㅣ니]旣긔曰왈一일初초[ㅣ면]豈긔無무更경新신[이리오]前젼者쟈編편配之지類류七칠百餘여人인[을]一일竝병特특放방[고]新신定뎡其기法법[노니]

身신爲위朝죠官관者쟈[와]以이士爲위名명者쟈[]勿물限한年년沿연海投투畀비[고]庶셔民민則즉江강邊변七칠邑읍[과]北븍關관六륙鎭진[과]萊府부外의[애]勿물論론公공私賤쳔[고]嚴엄刑형一일次後후邊변遠원[애]限한己긔身신爲위奴노婢비[호]釀양者쟈[와]飮음者쟈[]一일體톄施시律률[고]每年년歲셰首슈[애]倣방周쥬禮례[야]令령懸현法법京경外외官관門문[노니]是시何하意의哉[오]

此[]刑형期긔無무刑형之지義의也야[ㅣ라]吁후嗟차爾이等등[이]後후若약犯범焉언[이면]此[]爾이等등之지自犯범[이니]勿물以이不불敎교而이怨원予여[라]嗚오呼호[ㅣ라]予여[ㅣ]雖슈否부德덕[이나]爾이等등[이]若약思三삼十십年년可가愛其기君군之지心심[이면]欽흠體톄此敎교[야]莫막替톄予여意의[라]

噫희[라] 陟쳑降강[이]在上샹[시고]彼피蒼창[이]昭쇼臨림[시니] 予여何하敢감欺긔爾이[며]爾이何하敢감謾만予여乎호[ㅣ리오]嗚오呼호[ㅣ라]

國국之지興흥亡망[이]在此一일擧거[ㅣ라]咸함使聞문知지[노니]想샹宜의知지悉실[이어다]

Chinese Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

御製戒酒綸音

2. 何謂上負陟降一自禁酒之後, 每承慈聖稱美之敎, 因山纔訖, 今歲不盡, 而非徒不止甚至會飮, 陟降有知其以寡躬爲能禁乎否乎! 此所謂上負陟降也.

3. 何謂下閼霈典, 噫! 今春霈典, 往牒所無, 而至於犯酒者, 恐或弛禁一竝, 不赦今因處分而取覽徒流案, 則其數將近十百若此不已, 將不知至於幾十百, 此卽予不敎而令民陷法也.

4. 思之及此, 不覺懍然, 幾百徒流於春大赦不能放焉. 是豈同慶之意而今雖一倂放釋何與於赦典哉! 此所謂下閼霈典也.

6. 其君其臣之相與戒酒視小民雖有切焉, 以程子之大賢猶不無觀獵之悔, 況在凡人尤不可放心也.

7. 且以尙書訓體言之, 其宜竝諭臣庶, 又於心中不耐憧憧, 今曉祭畢後仍泣奏殿中曰, 于今酒禁之不行, 寔由一人, 一人其誰, 卽臣也. 此後酒若復行, 國必隨亡. 不戒其君, 雖無足道, 三百年宗社, 豈可由一人而亡哉!

9. 奏于列朝, 明降大何, 止于其身, 若於羣臣, 或知而不諫, 或身犯其戒者, 亦降大何, 使我海東臣庶, 無面謾之態, 諫而不聽, 咎亦在君臣何咎焉.

10. 以此口奏, 仍坐月臺召集陪祭宗親文武百官於殿庭, 洞諭予意言, 雖略意則盡矣. 噫! 上自股肱, 下至百僚, 體予爲宗社, 苦心其銘其佩, 莫替予意, 至於禁酒, 小民之犯者, 勿以摘得爲幸, 必以無刑爲期, 京而京尹部官外而方伯守令, 凡於對民也.

|

King Yeongjo’s Prohibition of Wine Drinking

2. Therefore, carrying the responsibility for my ancestors, I have to restrain [current practice] and to impose rules. I can blame only myself. I can blame only myself. How am I obliged to the ancestral spirits? Since I myself abstained from drinking, I have continuously received praises from my mother. The funeral is just over, and this year has not ended, but they not only not stop drinking, but they even get together to drink. Should the ancestral spirits know of this, would they think I am capable of this ban or not?! This is what I say by being obliged to the ancestral spirits. 3. What is meant by "to restrain my copious grace below"? Ah! This spring's general amnesty was unprecedented in the codes of the past. But as for those who had violated drinking prohibition, being afraid that it might rescind the restriction, none of them were released. Now based on this measurement, when I extract and survey a roster of executed and banished, their numbers reach tens of hundreds. If it goes on like this and does not stop, it will in no time reach several tens of hundreds. This is all because of me not instructing [well] and driving people into the traps of the law. 4. If I think about it up until this point, I cannot but think it regrettable. The several hundreds of those who received the punishment of forced labor and exile were unable to be released in spring. How could it be equal to the [true] meaning of celebration. Even though I release them all together now, how could it be equal to the [true] meaning of amnesty! This is why I say I blocked royal grace to below. 5. Then, how can I face my ancestors, when doing ritual at the Hyosojon [Hall of the Luminosity of Filial Piety] on the first day of a lunar month, and bowing to ancestors at the Chinjon [Hall of Royal Portraits] at dawn? Alas! Drinking is a wrong thing. That's why I could not avoid proclaiming in front of the masses to touch their minds. Nonetheless, it involves mere subjects and elderly, but does not cover high-ranking officials. Then, how can one say, that the court serves for the justice of the people? 6. The king and his subjects [should] abstain from drinking together and set an example for the petty people with all sincerity. But, for all that, even the sage Chenghao could not abandon his old habit easily (2), not to mention the uncultivated people. 7. Even though by the admonition style of the Book of Documents I have spoken, my words should be instructed to both ministers and commoners. My heart cannot help but be restless. After the early morning ritual had finished, I kept weeping in the assembly hall and said, "Now that the prohibition of wine-drinking is inefficient. It is all because of one person. Who is this person? It is none other than me, your servant". After this, if drinking wine returns to its prominent state, the state will eventually collapse. If one does not admonish the king, it amounts to nothing. But how could 300 years of the royal ancestral shrine be ruined because of one person? 8. Should I and the following kings that succeed me violate the wine prohibition, then even if the ministers and courtiers are not aware of [the violation of prohibition], even if the commoners and populace are not aware of [the violation of prohibition], [the violation of prohibition] will be obvious to the ancestral spirits, [it would be as clear] as if reflected in mirror. Should [I and the following kings that succeed me] violate it, it will be reported to the [ancestral spirits of] various preceding kings. 9. How great is my royal order? It comes to an end with me, if among the group of ministers, some know of this, but do not remonstrate or some themselves violated this prohibition. Let my subjects have no attitude of disguise, if they remonstrate and the king does not listen, the fault is also with the king, how can the fault lie with the ministers? 10. So I reported [to the spirits] the whole message above, yet I sat at the lunar platform and summoned royal kin, and civil and military bureaucrats to the courtyard. And then I communicated thoroughly my intention and words. The words were rather simple but enough to convey my intention thoroughly. Alas! All the officials in the bureaucracy from top to bottom should follow my example in serving dynasty alter with great efforts. Remember and put into practice my intention without any distortion. As for the prohibition, do not be contend with capturing petty offenders, but instead, try to ensure nobody should violate it. The chief magistrate of Seoul and his adjutants, and local governors and magistrates, it is your duty to serve people. 11. You must take seriously with whole your heart my command and fulfill it, even through tears. I let myself rule state affairs with painstaking efforts and I can't let my people fall into the net of destruction. The prosperity of the kingdom is a task of everyone and the merits will not remain hidden. Do not say that the royal throne is high and all the posts are low. Ruler and magistrates can only go together. The spirits of our forefathers are magnificent and the sky above is clearly blue. How you could be not afraid! How you could not worry! Every one of you, listen carefully and follow my instructions!

(1) The quotation is from the historical books of Han dynasty – Dong Guan Han Ji and Huo Han Shu (東觀漢記, 傳七, 馬廖; 後漢書, 列傳, 馬援列傳). (2) Chenghao (程顥, 1032-1085) was a neo-Confucian philosopher in the Song dynasty. He was addicted to hunting when he was young, but he abstained the habit after he devoted himself to study. However, it is said that he still felt itching when he saw others hunting even after 12 years. See: 《二程遗书》卷七:“猎,自谓今无此好。周茂叔曰:‘何言之易也,但此心潜隐未发,一日萌动,复如前矣。’后十二年。因见,果知未。”注云:“明道(即程颢)年十六七时,好田猎。十二年,暮归,在田野间见田猎者,不觉有喜心。” |

Discussion Questions

1. What is the function of alcohol in the ancestor rituals in Korea? What is the role of alcohol in Korean traditional culture in general?

2. How effective do you think the prohibition was in real life? And when did the prohibition end, on what premises?

3. Was the prohibition really only because of the harms of wine-drinking? Or, do you think there were other ulterior political motives? If so, what could they be?

4. What consequences could the prohibition have had on the economy? Can we find any sign of impact on the economy during Yeongjo's time?

5. To whom the document was addressed based on the language (use of characters and Korean alphabet)? Was it effective? How about the structure of the document? Is it relatively easy to read? Is it accessible? How about the logic of the text? Are King's descriptions of personal grievances effective? (for example, addressing the ancestral spirits in the hall of portraits). What kind of image of the King does the document present to the reader? What other rhetorical devices does he use? Is it more formulaic or more creative type of writing?

6. Why do you think drinking wines can be a crime? How does the king try to enforce this prohibition to the people? How does his strategy differ from law enforcement today?

7. What are the correlations between Confucian kingship and alcohol? In this sense, do you think that King Yongjo prohibited wine drinking, because he was more Confucian than any other kings of the Choson dynasty?

8. Yeongjo amnestied all criminals, but why did he particularly except the drinking violators from the amnestry? Was the increasing number of drinking people the real motivation?

9. How does this document illustrate the relationship between King Yongjo and his ministers as well as his commoner subjects? Why did King Yongjo specifically prohibit wine-drinking? Did he also implement other social control?

10. In Yeonjo’s decree on wine-prohibition, what is the ultimate authority that he appealed to? What does Yeongjo’s self-criticism tells us about the nature of Korean monarchy? Is this a unique Korean tradition?

11. What do you think is King Yeongjo’s personal opinion on consuming alcohol?

12. Why does his mother praise him for prohibiting alcohol?

13. Can there be any relationship between the death of the Crown Prince Sado and the Prohibition of Wine Drinking?

Further Readings

- View together with Record of Property Distribution among Brothers from 1621.

- ↑ "御製問業” in 《英祖大王》 (藏書閣, 2011) Vol. 15: 140-141.