"(Translation) 鄭澈 戒酒文"의 두 판 사이의 차이

| (사용자 2명의 중간 판 11개는 보이지 않습니다) | |||

| 25번째 줄: | 25번째 줄: | ||

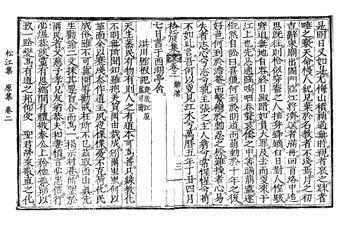

“An Essay on Quitting Alcohol” was written by the famous Chŏng Ch'ŏl (鄭澈 정철, 1536-1593) in 1578 and later compiled into a literary collection called Songgang's Prose Poetry Book (松江集) in 1894. Chŏng is regarded as one of the most prominent statemen and literati in Korean history. His poetry, in particular, is celebrated for its high literary value and still studied by many Koreans today. | “An Essay on Quitting Alcohol” was written by the famous Chŏng Ch'ŏl (鄭澈 정철, 1536-1593) in 1578 and later compiled into a literary collection called Songgang's Prose Poetry Book (松江集) in 1894. Chŏng is regarded as one of the most prominent statemen and literati in Korean history. His poetry, in particular, is celebrated for its high literary value and still studied by many Koreans today. | ||

| − | Besides the familiar story of his literary success, Chŏng is known for his fondness for alcohol. Among the many poems he wrote, there are some which can be categorized as “Poems of the Joy of Drinking (醉樂詩).” His fondness for alcohol, however, at times led him to major troubles in life. In 1591, Chŏng was implicated in a political struggle with the Easterners, Chŏng’s rival faction in the | + | Besides the familiar story of his literary success, Chŏng is known for his fondness for alcohol. Among the many poems he wrote, there are some which can be categorized as “Poems of the Joy of Drinking (醉樂詩).” His fondness for alcohol, however, at times led him to major troubles in life. In 1591, Chŏng was implicated in a political struggle with the Easterners, Chŏng’s rival faction in the Chosŏn court, surrounding the issue of installing the new crown prince. The political struggle not only ended unfavorably for Chŏng and his political allies, but also incurred the wrath of the Korean King Sŏnjo. Sŏnjo reportedly censured Chŏng for “incapable of doing anything other than indulging in alcohol and women and ruining the affairs of the state.” Chŏng was subsequently dismissed from his post and banished to the remote Myŏngch'ŏn (明川). |

| − | The above episode is just one of the many others in Chŏng’s life-long grapple with the notoriously vicious factional politics in | + | The above episode is just one of the many others in Chŏng’s life-long grapple with the notoriously vicious factional politics in Chosŏn history. Chŏng’s own father was twice banished to remote places in the kingdom when Chŏng was just 10 and 12. Chŏng’s elder brother was even brutally killed in one such political struggle after receiving the punishment of beating with heavy bamboo. |

| − | It is difficult to determine whether the harsh reality of the | + | It is difficult to determine whether the harsh reality of the Chosŏn politics contributed to Chŏng’s alcoholism, but “An Essay on Quitting Alcohol” offers a precious account of how this alcoholism was manifested in Chŏng’s life. Written in 1578, just one year after Chŏng decided to retreat back to his hometown Ch'angp'yŏng (昌平) from the Chosŏn court, the essay revealed Chŏng’s regret and shame in his alcoholic problems which likely had led to his decision to withdraw from politics a year earlier. |

| − | Other than its valuable insight into Chŏng’s own narration of his alcoholism, “An Essay on Quitting Alcohol” also provides a rare perspective into drinking culture in | + | Other than its valuable insight into Chŏng’s own narration of his alcoholism, “An Essay on Quitting Alcohol” also provides a rare perspective into drinking culture in Chosŏn Korea, which many would say still have an implication in Korean society today. |

| + | |||

| + | Reference: | ||

| + | |||

| + | "정철 鄭澈 [Chŏng Ch'ŏl]" Han'gung Minjong Munhwa Daebaek kwa Sajŏn 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture]. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%A0%95%EC%B2%A0&ridx=0&tot=81 (accessed 9 Sept 2019) | ||

| + | |||

| + | "송강집 松江集 [Songgang's Prose Poetry Book]" Han'gung Minjong Munhwa Daebaek kwa Sajŏn 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture]. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%86%A1%EA%B0%95%EC%A7%91&ridx=0&tot=4 (accessed 9 Sept 2019) | ||

=='''Original Script'''== | =='''Original Script'''== | ||

| 47번째 줄: | 53번째 줄: | ||

而動靜無常。言語失宜。千邪萬妄。皆從酒出。方其醉時。甘心行之。及其醒也。迷而不悟。人或言之。則初不信然。旣得其實。則羞媿欲死。今日如是。明日又如是。尤悔山積。補過無時。親者哀之。疏者唾之。褻天命。慢人紀。見棄於名敎者不淺焉。月之初吉。辭家廟。出國門。臨江將濟。送者滿舟。回首洛中。追思旣往。則恰似穿窬之人。抽身鋒鏑。白日對人。惶駭窘迫。無地自容。終日踧踖。如負大罪。 | 而動靜無常。言語失宜。千邪萬妄。皆從酒出。方其醉時。甘心行之。及其醒也。迷而不悟。人或言之。則初不信然。旣得其實。則羞媿欲死。今日如是。明日又如是。尤悔山積。補過無時。親者哀之。疏者唾之。褻天命。慢人紀。見棄於名敎者不淺焉。月之初吉。辭家廟。出國門。臨江將濟。送者滿舟。回首洛中。追思旣往。則恰似穿窬之人。抽身鋒鏑。白日對人。惶駭窘迫。無地自容。終日踧踖。如負大罪。 | ||

|| | || | ||

| − | However, odd actions and indecent words, all kinds of evils and audacities, all begin from alcohol. When I was drunk, I did whatever my heart told me to. When I later became sober, I was confused and did not understand [what happened]. When people told me what happened, I did not believe them at first. Then I began to realize the truth and was embarrassed to death. Today I made this kind of mistake. Tomorrow I would too make this kind of mistake. People close to me were sorrowful. People distant from me scorned me. I have desecrated Heaven’s will, disturbed human’s relations and abandoned the way of the Grand Masters (1). In the beginning of this month, I bid farewell to my home and ancestral hall, walked out of the capital’s gate and was about to board by the riverside (2). The boat was full of people who came to see me off. I looked back to the capital and reminisced about the past. I was like a disdained man who had to evade from the onslaught of blades and arrows (3). When I met people in broad daylight, I felt anxious and shamed and had nowhere to hide my face. All day I walked crouchingly as if I | + | However, odd actions and indecent words, all kinds of evils and audacities, all begin from alcohol. When I was drunk, I did whatever my heart told me to. When I later became sober, I was confused and did not understand [what happened]. When people told me what happened, I did not believe them at first. Then I began to realize the truth and was embarrassed to death. Today I made this kind of mistake. Tomorrow I would too make this kind of mistake. People close to me were sorrowful. People distant from me scorned me. I have desecrated Heaven’s will, disturbed human’s relations and abandoned the way of the Grand Masters (1). In the beginning of this month, I bid farewell to my home and ancestral hall, walked out of the capital’s gate and was about to board by the riverside (2). The boat was full of people who came to see me off. I looked back to the capital and reminisced about the past. I was like a disdained man who had to evade from the onslaught of blades and arrows (3). When I met people in broad daylight, I felt anxious and shamed and had nowhere to hide my face. All day I walked crouchingly as if I committed a great crime. |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| 60번째 줄: | 66번째 줄: | ||

萬曆五年丁丑四月七日。書于西湖亭舍。 | 萬曆五年丁丑四月七日。書于西湖亭舍。 | ||

|| | || | ||

| − | I departed and [the boat] was on the river. | + | I departed and [the boat] was [already] on the river. It was my father's death anniversary and I wept piteously. In the midst of grieve and sorrow, a seed of goodness in my heart sprouted up (4). I then lamented and sang a poem: |

| − | When it comes to the love of hunting, who can compare to Mingdao | + | When it comes to the love of hunting, who can compare to Mingdao? His urge to hunt still lingered after ten years (5). |

| − | When it comes to the love of women, who can compare to Danan | + | When it comes to the love of women, who can compare to Danan? His fondness of women still persisted after attempts to self-control (6). |

What is hard to control is human heart. | What is hard to control is human heart. | ||

| 95번째 줄: | 101번째 줄: | ||

(3) The phrase “穿窬之人” in the original text literally means “a person who sneaked through a hole in the wall” and commonly refer to thieves or, in broader interpretation of the word, any undesirable individual in society. For simplicity, the phrase is translated as “a disdained man.” | (3) The phrase “穿窬之人” in the original text literally means “a person who sneaked through a hole in the wall” and commonly refer to thieves or, in broader interpretation of the word, any undesirable individual in society. For simplicity, the phrase is translated as “a disdained man.” | ||

| − | (4) The phrase “善端” in the original text literally means “the beginning or inkling of goodness.” The author likely invokes the phrase here to refer to the “Four Beginnings of Goodness(四端),” an fundamental concept in Neo-Confucianism | + | (4) The phrase “善端” in the original text literally means “the beginning or inkling of goodness.” The author likely invokes the phrase here to refer to the “Four Beginnings of Goodness(四端),” an fundamental concept in Neo-Confucianism. |

| − | (5) This line of the poem refers to a well-known story at that time about Cheng Hao (程顥), one of the leading thinkers of Neo-Confucianism and who took on the courtesy name of Mingdao. Cheng was said to be particularly fond of hunting since he | + | (5) This line of the poem refers to a well-known story at that time about Cheng Hao (程顥), one of the leading thinkers of Neo-Confucianism and who took on the courtesy name of Mingdao. Cheng was said to be particularly fond of hunting since he was sixteen or seventeen. Later Cheng became immersed in his study and official career that he slowly quitted hunting. One time he told his friends lamentably that he no longer had the urge to hunt. |

One of his friends named Zhou Mao Shu (周茂叔) heard this and told Cheng, “Your words might not be true. I think you are not quitting hunting. It is just that you have buried this habit somewhere. Perhaps one day, your urge to hunt would be triggered again. And you would immediately return to hunting as you were in your youth.” Cheng listened to this but did not think much. He simply laughed along. | One of his friends named Zhou Mao Shu (周茂叔) heard this and told Cheng, “Your words might not be true. I think you are not quitting hunting. It is just that you have buried this habit somewhere. Perhaps one day, your urge to hunt would be triggered again. And you would immediately return to hunting as you were in your youth.” Cheng listened to this but did not think much. He simply laughed along. | ||

| 124번째 줄: | 130번째 줄: | ||

=='''Discussion Questions'''== | =='''Discussion Questions'''== | ||

| − | # | + | # Why did Chŏng Ch'ŏl write the essay? Who were the readers? How was the essay distributed and circulated? Was it commercially exchanged? |

| − | # | + | # What did the essay tell us about Korean culture? In particular, what did it tell us about alcohol consumption in pre-modern Korea? What was the incentive of encouraging people to take on a more healthy drinking habit? Neo-confucianism emphasizes personal cultivation. Do you think the call to restrain oneself from drinking excessively was related to the rise of Neo-Confucianism in Choson Korea?# Numbered list item |

| − | + | # Did the essay tell us anything about the factional conflicts in 16th century Korea? Try thinking about the relationship between Did the essay tell us anything about the factional conflicts in 16th century Korea? Try thinking about the relationship between Chŏng Ch'ŏl's career and the writing of this essay. | |

| + | <!-- | ||

| + | =='''Further Readings'''== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div style="color:#008080;"> | <div style="color:#008080;"> | ||

* View together with '''~~'''. | * View together with '''~~'''. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | ||

* | * | ||

* | * | ||

| + | --> | ||

| + | =='''References'''== | ||

| + | "정철 鄭澈 [Chŏng Ch'ŏl]" Han'gung Minjong Munhwa Daebaek kwa Sajŏn 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture]. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%A0%95%EC%B2%A0&ridx=0&tot=81 (accessed 9 Sept 2019) | ||

| + | |||

| + | "송강집 松江集 [Songgang's Prose Poetry Book]" Han'gung Minjong Munhwa Daebaek kwa Sajŏn 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture]. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%86%A1%EA%B0%95%EC%A7%91&ridx=0&tot=4 (accessed 9 Sept 2019) | ||

| − | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | + | <!-- | |

=='''Translation'''== | =='''Translation'''== | ||

| 242번째 줄: | 252번째 줄: | ||

[[Category:2019 JSG Summer Hanmun Workshop]] | [[Category:2019 JSG Summer Hanmun Workshop]] | ||

[[Category:Advanced Translation Group]] | [[Category:Advanced Translation Group]] | ||

| + | --> | ||

2022년 2월 15일 (화) 00:09 기준 최신판

| Primary Source | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Title | |

| English | An Essay on Quitting Alcohol | |

| Chinese | 戒酒文 | |

| Korean(RR) | 계주문(Gyejumun) | |

| Text Details | ||

| Genre | Literati Writings | |

| Type | 雜著 | |

| Author(s) | 鄭澈 | |

| Year | 1578 | |

| Source | Korean Classics and Literati's Collection of Writings (한국고전종합DB) | |

| Key Concepts | ||

| Translation Info | ||

| Translator(s) | Samuel Chan 陳世熙 진세희 | |

| Editor(s) | Samuel Chan 陳世熙 진세희 | |

| Year | 2019 | |

Introduction

“An Essay on Quitting Alcohol” was written by the famous Chŏng Ch'ŏl (鄭澈 정철, 1536-1593) in 1578 and later compiled into a literary collection called Songgang's Prose Poetry Book (松江集) in 1894. Chŏng is regarded as one of the most prominent statemen and literati in Korean history. His poetry, in particular, is celebrated for its high literary value and still studied by many Koreans today.

Besides the familiar story of his literary success, Chŏng is known for his fondness for alcohol. Among the many poems he wrote, there are some which can be categorized as “Poems of the Joy of Drinking (醉樂詩).” His fondness for alcohol, however, at times led him to major troubles in life. In 1591, Chŏng was implicated in a political struggle with the Easterners, Chŏng’s rival faction in the Chosŏn court, surrounding the issue of installing the new crown prince. The political struggle not only ended unfavorably for Chŏng and his political allies, but also incurred the wrath of the Korean King Sŏnjo. Sŏnjo reportedly censured Chŏng for “incapable of doing anything other than indulging in alcohol and women and ruining the affairs of the state.” Chŏng was subsequently dismissed from his post and banished to the remote Myŏngch'ŏn (明川).

The above episode is just one of the many others in Chŏng’s life-long grapple with the notoriously vicious factional politics in Chosŏn history. Chŏng’s own father was twice banished to remote places in the kingdom when Chŏng was just 10 and 12. Chŏng’s elder brother was even brutally killed in one such political struggle after receiving the punishment of beating with heavy bamboo.

It is difficult to determine whether the harsh reality of the Chosŏn politics contributed to Chŏng’s alcoholism, but “An Essay on Quitting Alcohol” offers a precious account of how this alcoholism was manifested in Chŏng’s life. Written in 1578, just one year after Chŏng decided to retreat back to his hometown Ch'angp'yŏng (昌平) from the Chosŏn court, the essay revealed Chŏng’s regret and shame in his alcoholic problems which likely had led to his decision to withdraw from politics a year earlier.

Other than its valuable insight into Chŏng’s own narration of his alcoholism, “An Essay on Quitting Alcohol” also provides a rare perspective into drinking culture in Chosŏn Korea, which many would say still have an implication in Korean society today.

Reference:

"정철 鄭澈 [Chŏng Ch'ŏl]" Han'gung Minjong Munhwa Daebaek kwa Sajŏn 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture]. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%A0%95%EC%B2%A0&ridx=0&tot=81 (accessed 9 Sept 2019)

"송강집 松江集 [Songgang's Prose Poetry Book]" Han'gung Minjong Munhwa Daebaek kwa Sajŏn 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture]. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%86%A1%EA%B0%95%EC%A7%91&ridx=0&tot=4 (accessed 9 Sept 2019)

Original Script

| Classical Chinese | English |

|---|---|

|

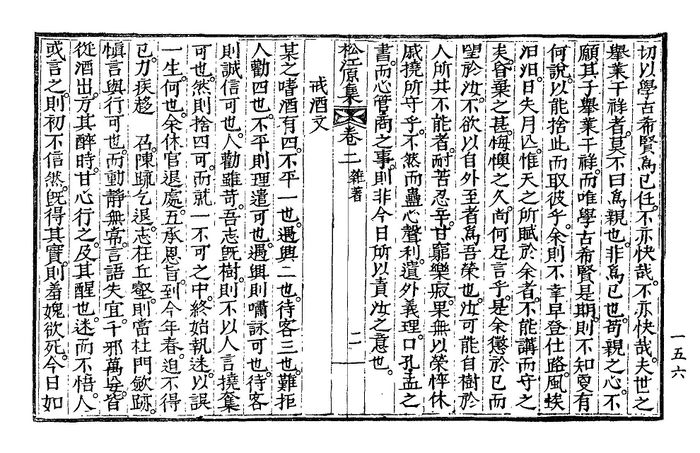

某之嗜酒有四。不平一也。遇興二也。待客三也。難拒人勸四也。不平則理遣可也。遇興則嘯詠可也。待客則誠信可也。人勸雖苛。吾志旣樹。則不以人言撓奪可也。然則捨四可。而就一不可之中。終始執迷。以誤一生。何也。余休官退處。五承恩旨。到今年春。迫不得已。力疾趨召。陳疏乞退。志在丘壑。則當杜門斂跡。愼言與行可也。 |

There are four reasons that I indulge in alcohol. First, it is that I encounter injustice. Second, it is that I am in a jolly mood. Third, it is that I have to receive guests. Fourth, it is that I find it difficult to turn down people’ offer to drink. When I encounter injustice, I can just resolve [my grievances] with reasons. When I am in a jolly mood, I can just sing songs. When I have to receive guests, I can just treat them with sincerity. Although it is difficult to turn down people’s offer to drink, if my will is strong as a tree, I can just not be tempted and submitted to people’s words. However, if one abandons these four ways [to resist alcoholism] and gives in one time, he or she would fall into obsession and ruin his or her life. How is this so? I had taken a break from my office and retreated to my home. Five times had I received imperial edicts [that requested me to go back to the court.] In Spring this year, I suffered from an unmanageable illness and had no choice but to memorialize and plead for retirement. My will was as unmovable as mountains. All that I had to do was withdrawing into my home, limiting my presence and being mindful of my words and actions. |

|

而動靜無常。言語失宜。千邪萬妄。皆從酒出。方其醉時。甘心行之。及其醒也。迷而不悟。人或言之。則初不信然。旣得其實。則羞媿欲死。今日如是。明日又如是。尤悔山積。補過無時。親者哀之。疏者唾之。褻天命。慢人紀。見棄於名敎者不淺焉。月之初吉。辭家廟。出國門。臨江將濟。送者滿舟。回首洛中。追思旣往。則恰似穿窬之人。抽身鋒鏑。白日對人。惶駭窘迫。無地自容。終日踧踖。如負大罪。 |

However, odd actions and indecent words, all kinds of evils and audacities, all begin from alcohol. When I was drunk, I did whatever my heart told me to. When I later became sober, I was confused and did not understand [what happened]. When people told me what happened, I did not believe them at first. Then I began to realize the truth and was embarrassed to death. Today I made this kind of mistake. Tomorrow I would too make this kind of mistake. People close to me were sorrowful. People distant from me scorned me. I have desecrated Heaven’s will, disturbed human’s relations and abandoned the way of the Grand Masters (1). In the beginning of this month, I bid farewell to my home and ancestral hall, walked out of the capital’s gate and was about to board by the riverside (2). The boat was full of people who came to see me off. I looked back to the capital and reminisced about the past. I was like a disdained man who had to evade from the onslaught of blades and arrows (3). When I met people in broad daylight, I felt anxious and shamed and had nowhere to hide my face. All day I walked crouchingly as if I committed a great crime. |

|

及去而更來于江上也。先忌適臨。嗚咽呑聲。哀慘之中。善端萌露。遂慨然自訟曰。 喜獵何到於明道。而萌動於十年之後。 好色何到於澹菴。而繫戀於動忍之餘。 難操者心。易失者志。心兮志兮。孰主張之。主人翁兮。常惺惺兮。苟不如此言。吾何以更見江水兮。 萬曆五年丁丑四月七日。書于西湖亭舍。 |

I departed and [the boat] was [already] on the river. It was my father's death anniversary and I wept piteously. In the midst of grieve and sorrow, a seed of goodness in my heart sprouted up (4). I then lamented and sang a poem: When it comes to the love of hunting, who can compare to Mingdao? His urge to hunt still lingered after ten years (5). When it comes to the love of women, who can compare to Danan? His fondness of women still persisted after attempts to self-control (6). What is hard to control is human heart. What is easy to lose is will (7). Oh, human heart. Oh, will. Who may master you. Oh my father, I pledge to remain sober. If I fail to live up to these words, how can I see the river again?

|

|

Notes: (1) Grand Masters here refer to the Grand Masters of Confucianism (2) The phrase “初吉” in the original text refers to the first to the seventh day of a month. For simplicity, the phrase is translated as “the beginning of this month.” (3) The phrase “穿窬之人” in the original text literally means “a person who sneaked through a hole in the wall” and commonly refer to thieves or, in broader interpretation of the word, any undesirable individual in society. For simplicity, the phrase is translated as “a disdained man.” (4) The phrase “善端” in the original text literally means “the beginning or inkling of goodness.” The author likely invokes the phrase here to refer to the “Four Beginnings of Goodness(四端),” an fundamental concept in Neo-Confucianism. (5) This line of the poem refers to a well-known story at that time about Cheng Hao (程顥), one of the leading thinkers of Neo-Confucianism and who took on the courtesy name of Mingdao. Cheng was said to be particularly fond of hunting since he was sixteen or seventeen. Later Cheng became immersed in his study and official career that he slowly quitted hunting. One time he told his friends lamentably that he no longer had the urge to hunt. One of his friends named Zhou Mao Shu (周茂叔) heard this and told Cheng, “Your words might not be true. I think you are not quitting hunting. It is just that you have buried this habit somewhere. Perhaps one day, your urge to hunt would be triggered again. And you would immediately return to hunting as you were in your youth.” Cheng listened to this but did not think much. He simply laughed along. 12 years later, the words of Zhou came true. One time, Cheng went out to the countryside and saw someone hunting. He was immediately tempted to hunt again. But he remembered the words of Zhou and decided to suppress his urge. He then simply went home. The story was recorded by many contemporaries, including Zhu Xi, and commonly cited as an allegory of a person who is able to control his or her desire and maintain his or her moral integrity. Reference: 晉宋朱熹<近思錄>:「明道先生年十六、十七時,好畋獵。十二年,暮歸,在田野間見畋獵者,不覺有喜心。」 “見獵心喜,” 關西國小成語教學網, http://163.19.66.6/idiom/4-54.htm (6) This line of the poem refers to a story about He Quan (胡铨), a renowned minister in the Southern Song and who took on the courtesy name of Danan (澹庵). At one point of his career, He was involved in a fractional struggle with the infamous Qin Gui (秦檜), an influential power broker in the Song court. He was demoted and transferred to the remote South for more than 10 years. When he later returned to the court, he fell in love with a courtesan and was once again implicated in much controversy. Zhu Xi heard of He’s deeds and composed a poem to warn people of the danger of sexual temptation. The poem is cited as followed: 十年浮海一身輕,歸對梨渦卻有情。世上無如人欲險,幾人到此誤平生。 Reference: “世上无如人欲险,” 人民報, https://m.renminbao.com/rmb/articles/2007/1/26/43004m.html (7) This is a reference to a famous teaching in The Works of Mencius (孟子) in which the Confucius was quoted to say, "操則存,舍則亡." |

Discussion Questions

- Why did Chŏng Ch'ŏl write the essay? Who were the readers? How was the essay distributed and circulated? Was it commercially exchanged?

- What did the essay tell us about Korean culture? In particular, what did it tell us about alcohol consumption in pre-modern Korea? What was the incentive of encouraging people to take on a more healthy drinking habit? Neo-confucianism emphasizes personal cultivation. Do you think the call to restrain oneself from drinking excessively was related to the rise of Neo-Confucianism in Choson Korea?# Numbered list item

- Did the essay tell us anything about the factional conflicts in 16th century Korea? Try thinking about the relationship between Did the essay tell us anything about the factional conflicts in 16th century Korea? Try thinking about the relationship between Chŏng Ch'ŏl's career and the writing of this essay.

References

"정철 鄭澈 [Chŏng Ch'ŏl]" Han'gung Minjong Munhwa Daebaek kwa Sajŏn 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture]. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%A0%95%EC%B2%A0&ridx=0&tot=81 (accessed 9 Sept 2019)

"송강집 松江集 [Songgang's Prose Poetry Book]" Han'gung Minjong Munhwa Daebaek kwa Sajŏn 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture]. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%86%A1%EA%B0%95%EC%A7%91&ridx=0&tot=4 (accessed 9 Sept 2019)